When we talked about string interning earlier, we mentioned a concept that Go uses to implement its unique map feature: the “weak pointer.” We kind of breezed through it back then to stay on track with the main flow of that article.

If you haven’t checked that piece out yet, I’d highly recommend giving it a read: Inside Go’s Unique Package: String Interning Simplified. It’s one of those optimization tricks that makes VictoriaMetrics’ products faster. You can read it before or after this one—totally up to you.

So, what’s a weak pointer?

#

A weak pointer is basically a way to reference a chunk of memory without locking it down, so the garbage collector can clean it up if no one else is actively holding onto it.

“Why even bother with weak pointers? Does Go even have them?”

Well, yes, Go does have the weak pointer concept. It’s part of the weak package, which is tied pretty closely to the Go runtime. Interestingly, it used to be more of an internal tool, but recently there’s been a push to make it public through this proposal.

Pretty cool, right?

The key thing about weak pointers is that they’re safe. If the memory they’re pointing to gets cleaned up, the weak pointer automatically becomes nil — so there’s no risk of accidentally pointing to freed memory. And when you do need to hold onto that memory, you can convert a weak pointer into a strong one. That strong pointer tells the garbage collector, “Hey, hands off this memory while I’m using it.”

“Wait, it just turns into nil automatically? That sounds… risky.”

Yep, weak pointers can definitely become nil — sometimes at moments you’re not expecting.

They’re trickier to use than regular pointers. At any point, a weak pointer can turn nil if the memory it points to gets cleaned up. This happens when no strong pointers are holding onto that memory. So, it’s really important to always check if the strong pointer that you just converted from a weak pointer is nil.

Now, about when this cleanup happens — it’s not immediate. Even when no one’s referencing the memory, the cleanup moment is totally up to the garbage collector.

“Alright, show me some code!”

At the time of writing, the weak package isn’t officially released yet. It’s expected to land in Go 1.24. But we can sneak a peek at the source code and play around with it. The package gives you two main APIs:

weak.Make: creates a weak pointer from a strong pointer.weak.Pointer[T].Strong: converts a weak pointer back into a strong pointer.

Here’s an example:

type T struct {

a int

b int

}

func main() {

a := new(string)

println("original:", a)

// make a weak pointer

weakA := weak.Make(a)

runtime.GC()

// use weakA

strongA := weakA.Strong()

println("strong:", strongA, a)

runtime.GC()

// use weakA again

strongA = weakA.Strong()

println("strong:", strongA)

}

// Output:

// original: 0x1400010c670

// strong: 0x1400010c670 0x1400010c670

// strong: 0x0

And here’s what’s happening in the code:

- After the first garbage collection (

runtime.GC()), the weak pointerweakAstill points to the memory because we’re still using the variableain theprintln("strong:", strongA, a)line. The memory can’t be cleaned up yet since it’s in use. - But when the second garbage collection runs, the strong reference (

a) isn’t used anymore. That means the garbage collector can safely clean up the memory, leavingweakA.Strong()to returnnil.

Now, if you try this code with something other than a string pointer—like a *int, *bool, or some other type, you might notice different behavior, the last strong output may not be nil.

This has to do with how Go handles “tiny objects” like int, bool, float32, float64, etc. These types are allocated as tiny objects, and even if they’re technically unused, the garbage collector might not clean them up right away during garbage collection. To understand more about this, you can dive deeper into tiny object allocation in Go Runtime Finalizer and Keep Alive.

Weak pointers can be really practical for managing memory in specific scenarios.

- For example, they’re great for canonicalization maps — situations where you only want to keep one copy of a piece of data around. This ties back to our earlier discussion on string interning.

- Another case is when you want the lifespan of some memory to match the lifespan of another object, similar to how JavaScript’s WeakMap works. WeakMaps allow objects to be cleaned up automatically when they’re no longer in use.

So, the main benefit of weak pointers is they let you tell the garbage collector, “Hey, it’s okay to get rid of this resource if no one’s using it — I can always recreate it later.” This works well for objects that take up significant memory but don’t need to stick around unless they’re actively being used.

How do weak pointers work?

#

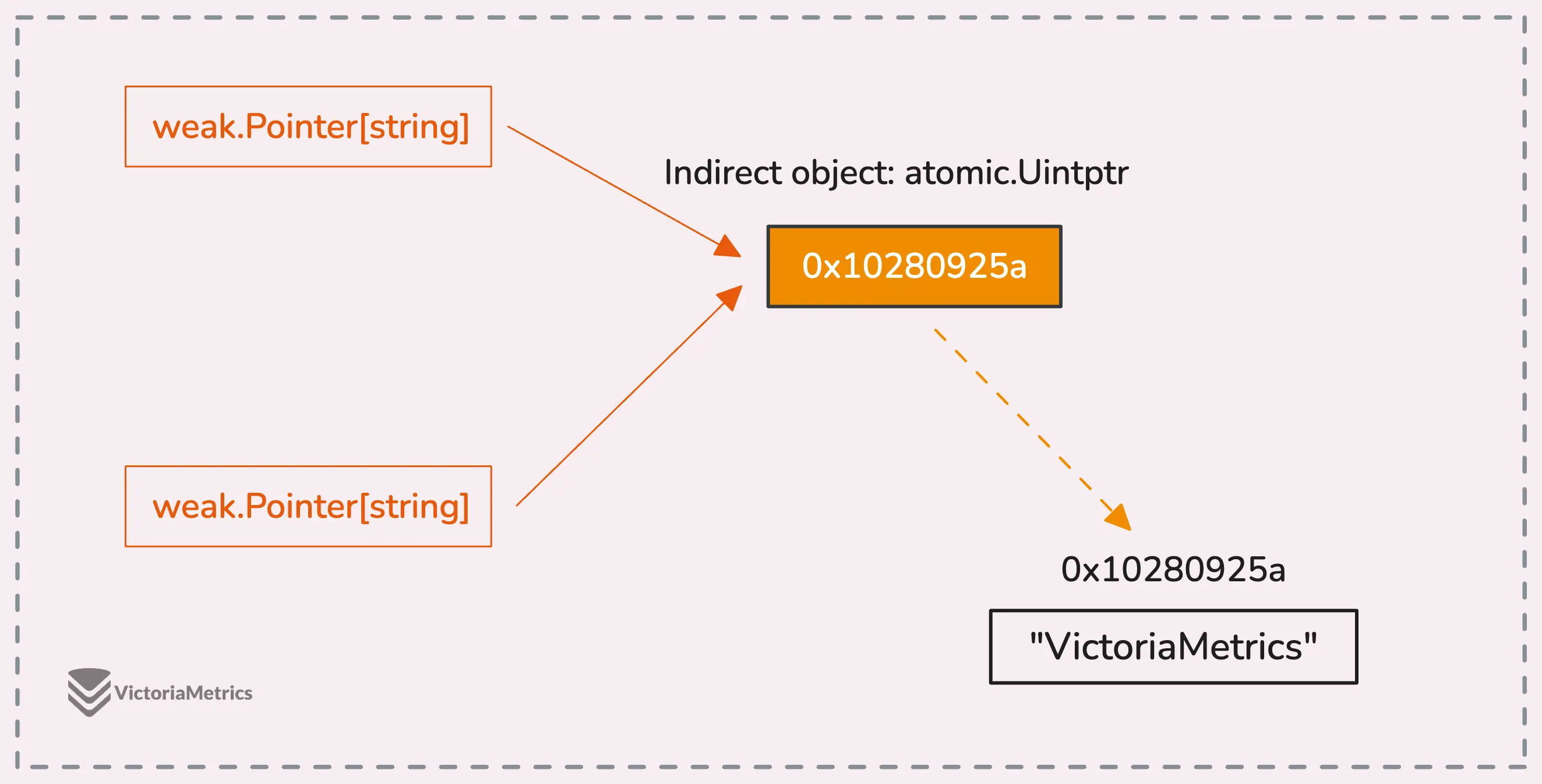

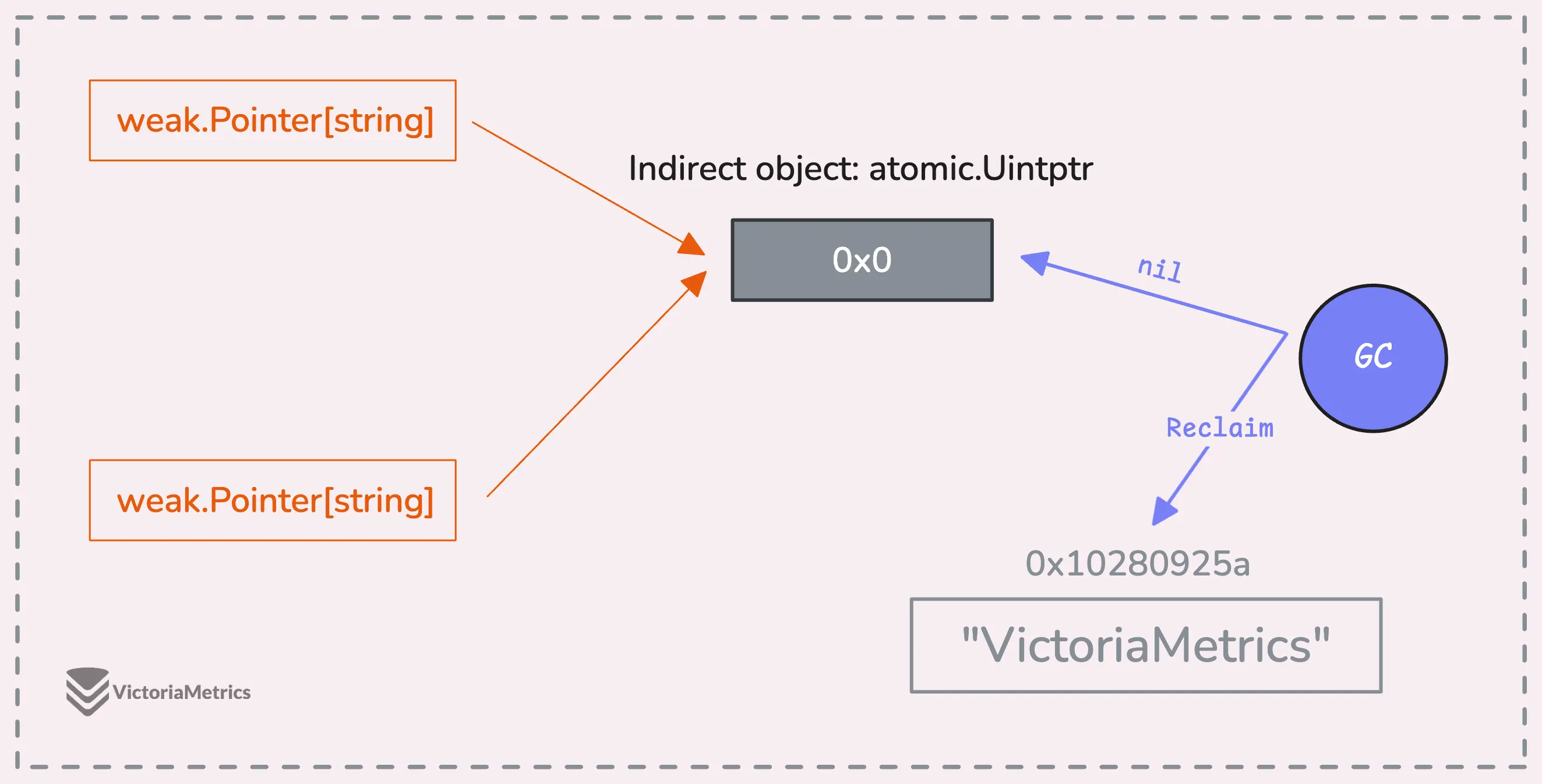

Interestingly, weak pointers don’t actually point directly to the memory they reference. Instead, they’re simple structs (using generics) that hold an “indirection object.” This object is tiny, just 8 bytes, and it points to the actual memory target.

type Pointer[T any] struct {

u unsafe.Pointer

}

Why design it this way?

This setup lets the garbage collector clean up weak pointers to a specific object all at once, efficiently. When it decides the memory should be freed, the collector only needs to set the pointer in the indirection object to nil (or 0x0). It doesn’t have to go around updating each weak pointer individually.

On top of that, this design supports equality checks (==). Weak pointers created from the same original pointer will be treated as “equal,” even after the object they point to has been garbage collected.

func main() {

a := new(string)

// make a weak pointers

weakA := weak.Make(a)

weakA2 := weak.Make(a)

println("Before GC: Equality check:", weakA == weakA2)

runtime.GC()

// Test their equality

println("After GC: Strong:", weakA.Strong(), weakA2.Strong())

println("After GC: Equality check:", weakA == weakA2)

}

// Before GC: Equality check: true

// After GC: Strong: 0x0 0x0

// After GC: Equality check: true

This works because weak pointers from the same original object share the same indirection object. When you call weak.Make, if an object already has a weak pointer associated with it, the existing indirection object gets reused instead of creating a new one.

“Wait, isn’t using 8 bytes for an indirection object a bit wasteful?”

It might seem like it, but the author would say, this isn’t a big issue. Weak pointers are typically used in cases where the overall goal is to save memory. For example, in canonicalization maps — where you eliminate duplicates by keeping only one copy of each unique piece of data — you’re already saving a lot of memory by avoiding redundancy.

That said, if you’re using weak pointers in a scenario where there are tons of unique items and few duplicates, you could end up using more memory than expected. So, it’s important to consider the specific use case when deciding if weak pointers are the right tool for the job.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.