- Blog /

- Inside Go's Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

Inside Go's Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

One of the optimizations used in VictoriaMetrics’ source code is something called string interning. We actually have a post in our optimization series that dives into this Performance optimization techniques in time series databases: strings interning.

To explain what that means, in Go 1.23, the Go team rolled out this new ‘unique’ package. It’s all about dealing with duplicates in a “smart” way.

- Michael Knyszek wrote a great blog post breaking it down: New unique package.

- If you’re interested in more numbers, Valentin Deleplace’s article also goes from problem to solution with some cool stats on memory savings: Interning in Go.

So, the idea is pretty simple.

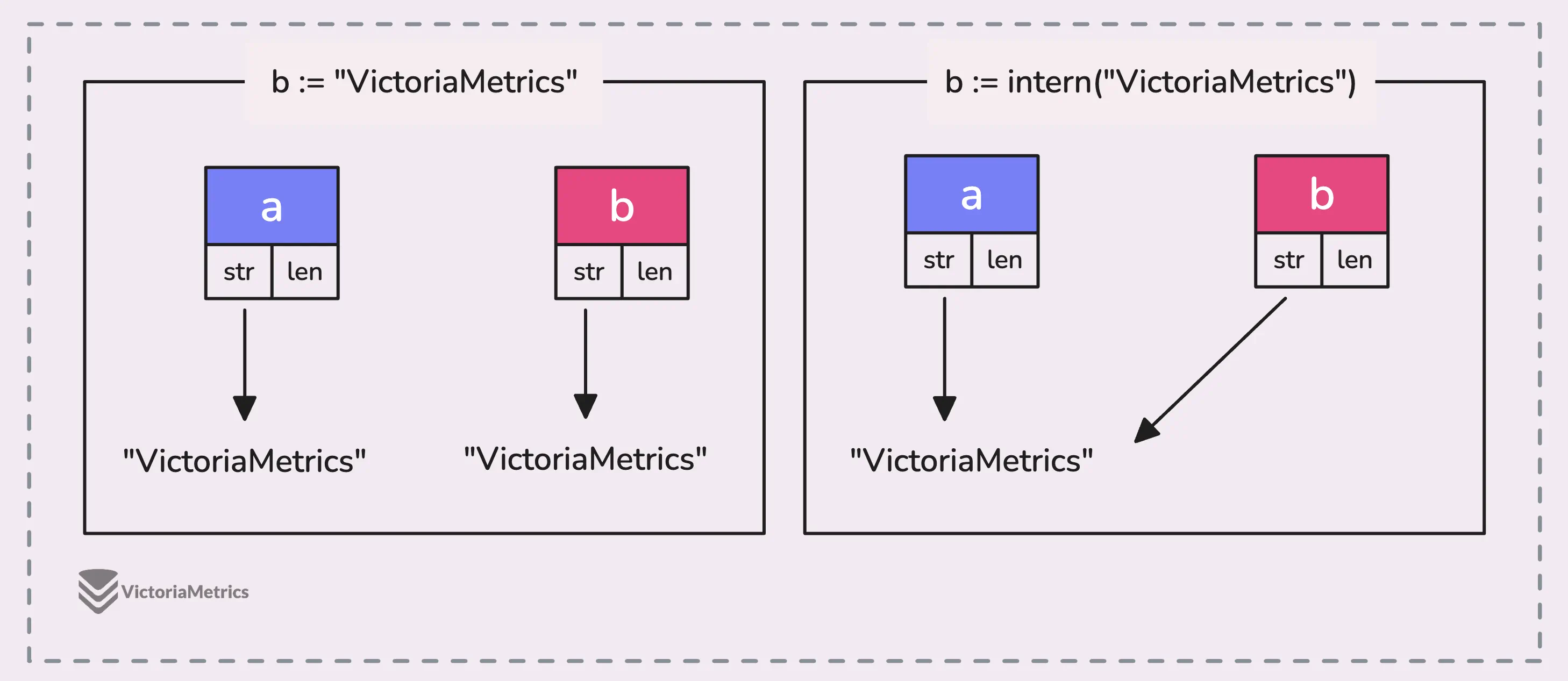

When you’ve got several identical values in your code, you only store one copy. Instead of having several copies of the same thing, they all just point to this one version, which is a lot more efficient. It’s a process often called ‘interning’ in programming circles.

The big win here is memory savings. You’re not wasting space on multiple copies of the same value floating around.

You’ve got just one true, official version, and everything else points back to it. And the beauty of the ‘unique’ package is that it manages all of this for you behind the scenes. You don’t really have to think about it too much and Go takes care of the heavy lifting.

Why String Interning?

#

In our previous article, we gave a quick demo using a map to implement a naive version of string interning:

var internStringsMap = make(map[string]string)

func intern(s string) string {

m := internStringsMap

if v, ok := m[s]; ok {

return v

}

m[s] = s

return s

}

When you pass a string s to the intern function, it checks if that string is already hanging out in internStringsMap. If it is, we skip storing a duplicate and just return the version that’s already there. If it’s not in the map, we go ahead and store it, and next time the same string pops up, we just reuse the stored version.

Simple, right?

“Pointless! Doesn’t Go just copy the string every time you pass it to a function or return it?”

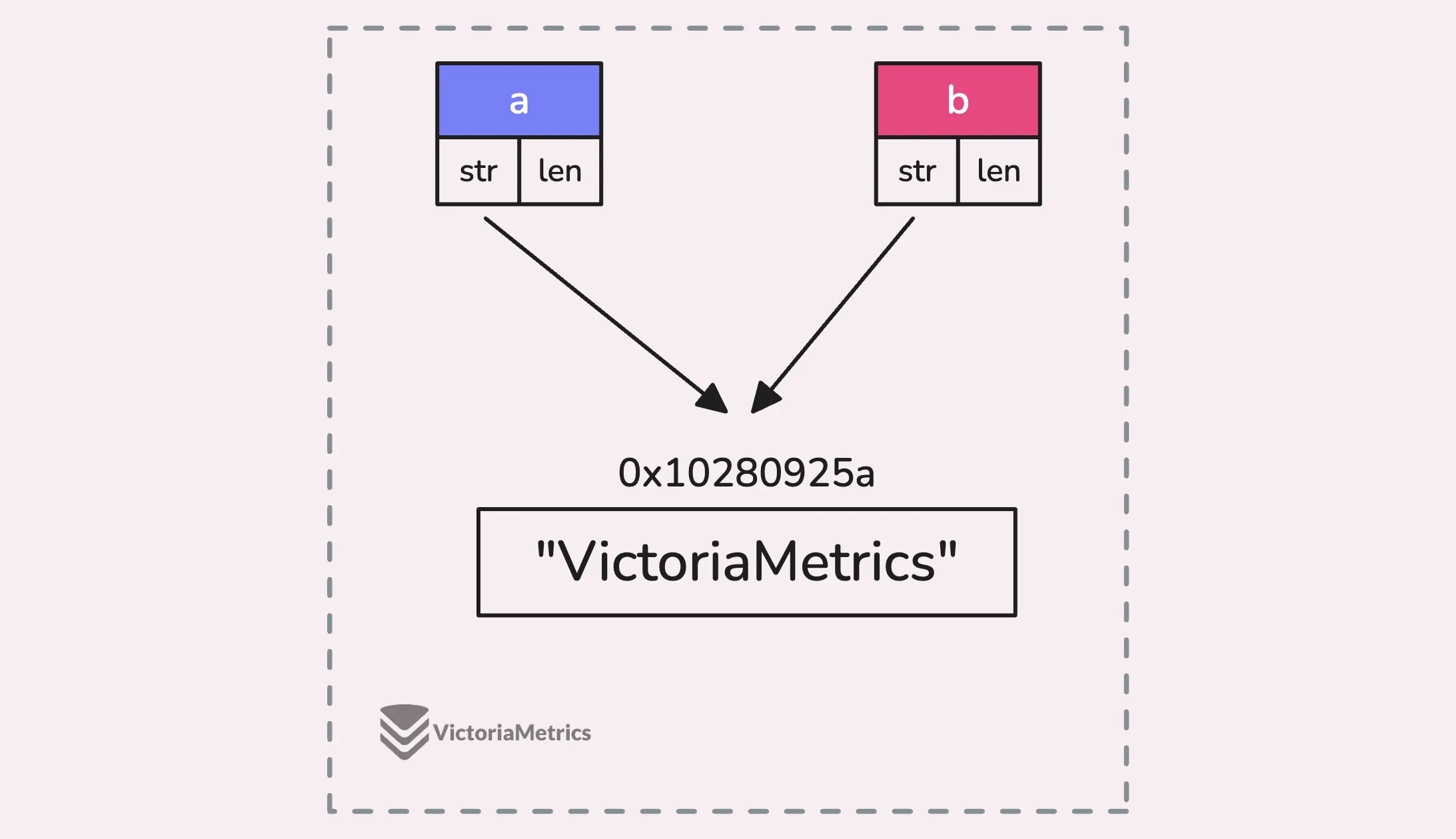

Strings in Go behave a lot like slices and when you assign a string to a new variable, say from a to b, Go doesn’t copy the actual value, like the string “VictoriaMetrics”, but instead just copies what’s called the “string header,” similar to a slice header.

For more information about slice: Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

So both a and b end up pointing to the same underlying byte array.

type stringStruct struct {

str unsafe.Pointer // []byte

len int

}

And before someone asks “But isn’t that risky? What if one of them changes the string?”, it’s fine.

Go enforces that strings are immutable (at least in normal situations), so even though they share the same memory, neither can change the underlying value. The key point here is, how do we take advantage of this shared underlying byte array to save memory when we’ve got identical string values?

That’s where string interning comes in, it ensures that all identical strings share the same byte array, cutting down on memory usage.

But the version of string interning we showed above isn’t thread-safe. You can’t just throw it into a situation with multiple goroutines. Go’s maps don’t play well with concurrent access and modification, so if you’re going concurrency, you’ll need something safer.

For more on how Go maps actually work: Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

So, we tried another approach using sync.Map to solve the concurrency issue:

var internStringsMap sync.Map

func intern(s string) string {

m := &internStringsMap

interned, _ := m.LoadOrStore(s, s)

return interned.(string)

}

Alright, this solves the problem of concurrent access and modification, which is great.

But, we’ve still got another issue as the more unique values you add, the bigger that map gets, and eventually, you’re staring down the barrel of unbounded memory growth. Without some kind of cleanup mechanism, this thing will just keep growing forever, which is not ideal.

We could resolve this with a simple time-to-live (TTL) mechanism for each key or the entire key-value pair. This increases complexity, but you can reference how VictoriaMetrics handles it.

The Go unique package takes a different strategy, similar to sync.Pool, and it will also be discussed in this article.

There’s another perk, or a benefit to string interning that Michael Knyszek pointed out: faster equality checks.

Normally, comparing two strings works like this:

- First, you check if they start at the same memory address (basically comparing pointers) and whether their lengths match.

- If neither of those is true, you’re stuck comparing the strings byte by byte.

Sure, Go might optimize it so it’s not literally checking byte by byte (chunk by chunk), but still, comparing two long strings is expensive if they’re identical since you’re checking all the way to the last byte.

If you’ve interned all of your strings, meaning there’s only one canonical copy of each distinct string in memory, you can just compare the memory addresses (the pointers). If the pointers are the same, the strings are definitely equal.

No need to go through the bytes, no need to worry about the lengths—just a quick pointer comparison, and you’re done.

Unique Package

#

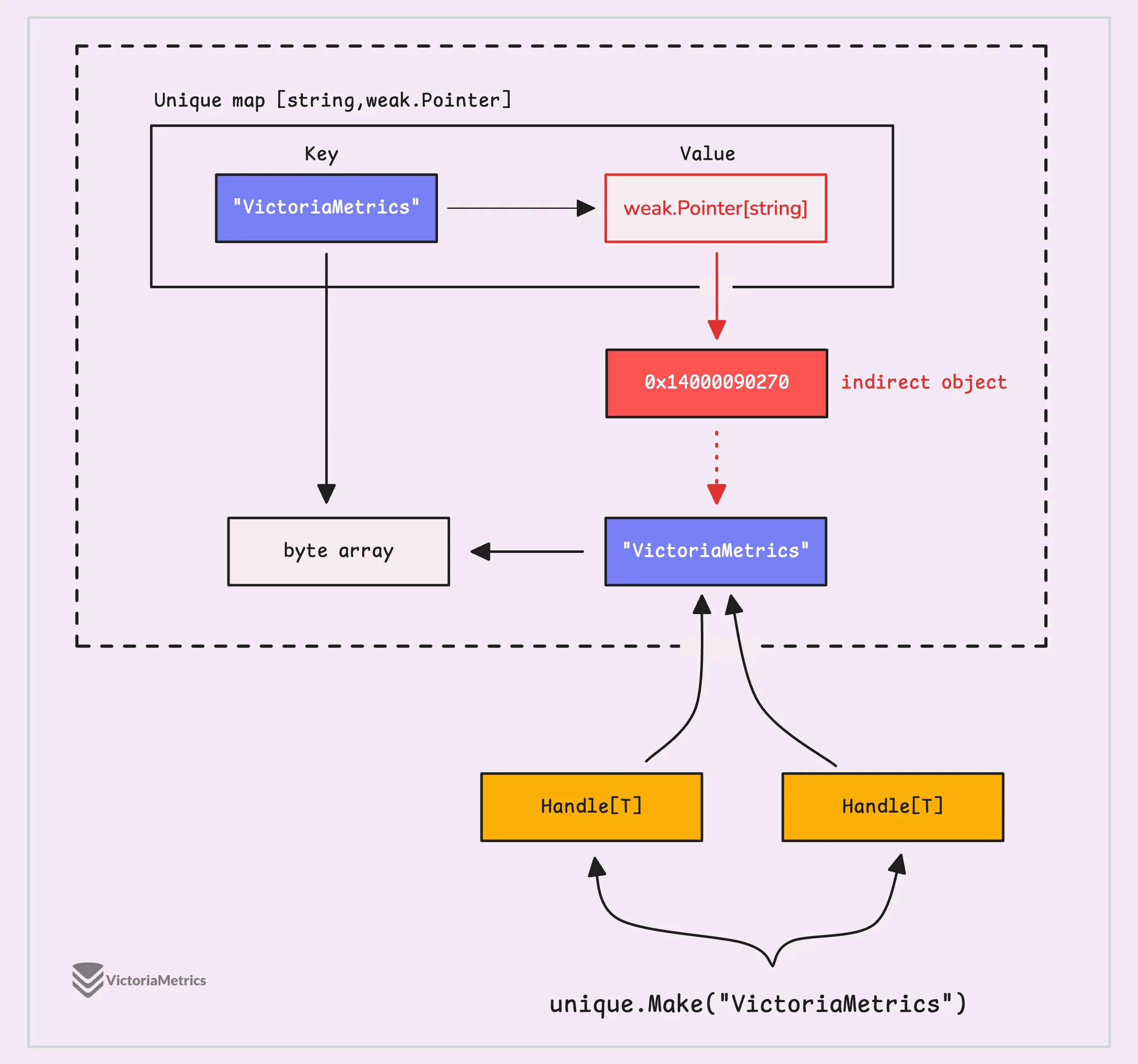

The unique package only exposes two main public pieces: the type Handle[T] and the function Make[T]().

Here’s what it looks like:

package unique

// Handle is a globally unique identity for some value of type T.

type Handle[T comparable] struct {

value *T

}

// Make returns a globally unique handle for a value of type T. Handles

// are equal if and only if the values used to produce them are equal.

func Make[T comparable](value T) Handle[T] { ... }

The Make function is designed to give you a canonical, globally unique handle for any comparable value you pass in.

Instead of just returning the value itself, it hands you a Handle[T], which works as a kind of reference to that value. This handle lets you efficiently compare values and manage memory without worrying about having multiple copies of the same thing floating around in memory.

In other words, when you call Make with the same value over and over, you’ll always get the same Handle[T].

So, if two handles are equal, you know for sure that their underlying values are also equal. Comparing handles is way more efficient than comparing the values themselves, especially if those values are large or complex. Instead of doing a deep dive into the actual content of the value, you just compare the handles, since they’re really just pointers, it’s fast.

Let’s break this down with a simple “Hello, World” example:

func main() {

h1 := unique.Make("Hello")

h2 := unique.Make("Hello")

w1 := unique.Make("World")

fmt.Println("h1:", h1)

fmt.Println("h2:", h2)

fmt.Println("w1:", w1)

fmt.Println("h1 == h2:", h1 == h2)

fmt.Println("h1 == w1:", h1 == w1)

}

// Output:

// h1: {0x14000090270}

// h2: {0x14000090270}

// w1: {0x14000090280}

// h1 == h2: true

// h1 == w1: false

In the output, you’ll notice that h1 and h2 both point to the same memory address (0x14000090270), while w1 has a different address (0x14000090280). The equality check between h1 and h2 (h1 == h2) is based on comparing these pointers, not the actual content of the strings. This makes the comparison sidesteps the need to check each character of the strings themselves.

And what makes unique even more powerful is, it’s not limited to just strings, you can intern any comparable type.

We can indeed see how this is used in practice by taking a look at the source code of the net/netip package, the Go team decided to use the unique package to intern the IPv6 zone name within a struct called addrDetail:

package netip

type addrDetail struct {

isV6 bool // IPv4 is false, IPv6 is true.

zoneV6 string // != "" only if IsV6 is true.

}

var (

z0 unique.Handle[addrDetail]

z4 = unique.Make(addrDetail{})

z6noz = unique.Make(addrDetail{isV6: true})

)

func (ip Addr) WithZone(zone string) Addr {

if !ip.Is6() {

return ip

}

if zone == "" {

ip.z = z6noz

return ip

}

ip.z = unique.Make(addrDetail{isV6: true, zoneV6: zone})

return ip

}

If you have an IPv6 address with a zone, it gets stored in a unique handle.

Before switching to the unique package, this code also used a custom interning solution from their internal package, internal/intern, which was itself a port of the interning logic from https://github.com/go4org/intern.

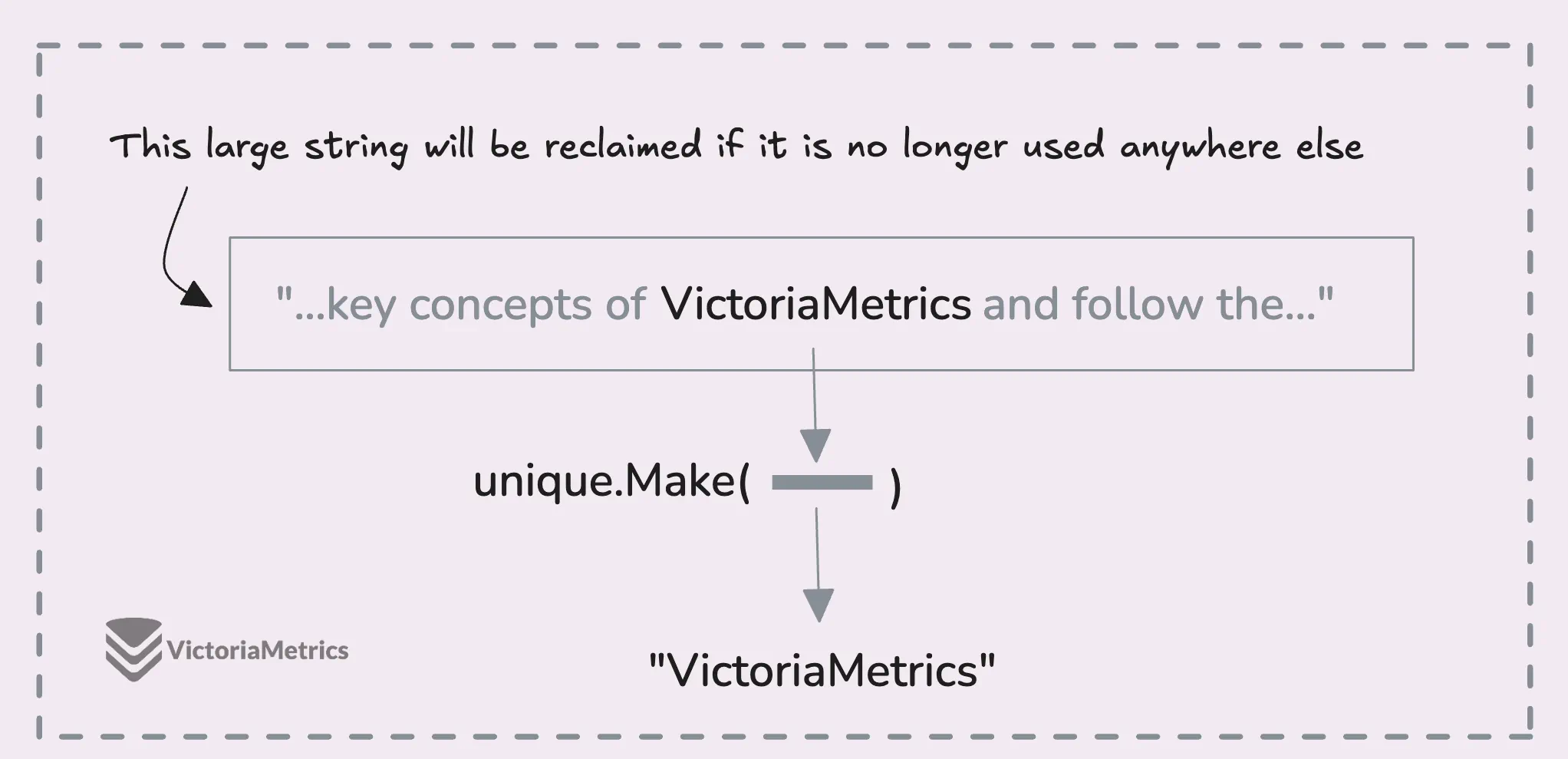

Another hidden gem about interning string is, if you intern a substring of a large string, even though both the substring and the original string share the same underlying byte array, the large string can still be garbage collected if it’s no longer in use anywhere else in the program.

So, you get to keep the memory savings from the interning without holding on to the full original string unnecessarily.

With that covered, let’s move on to how this all works under the hood.

How Interning Works

#

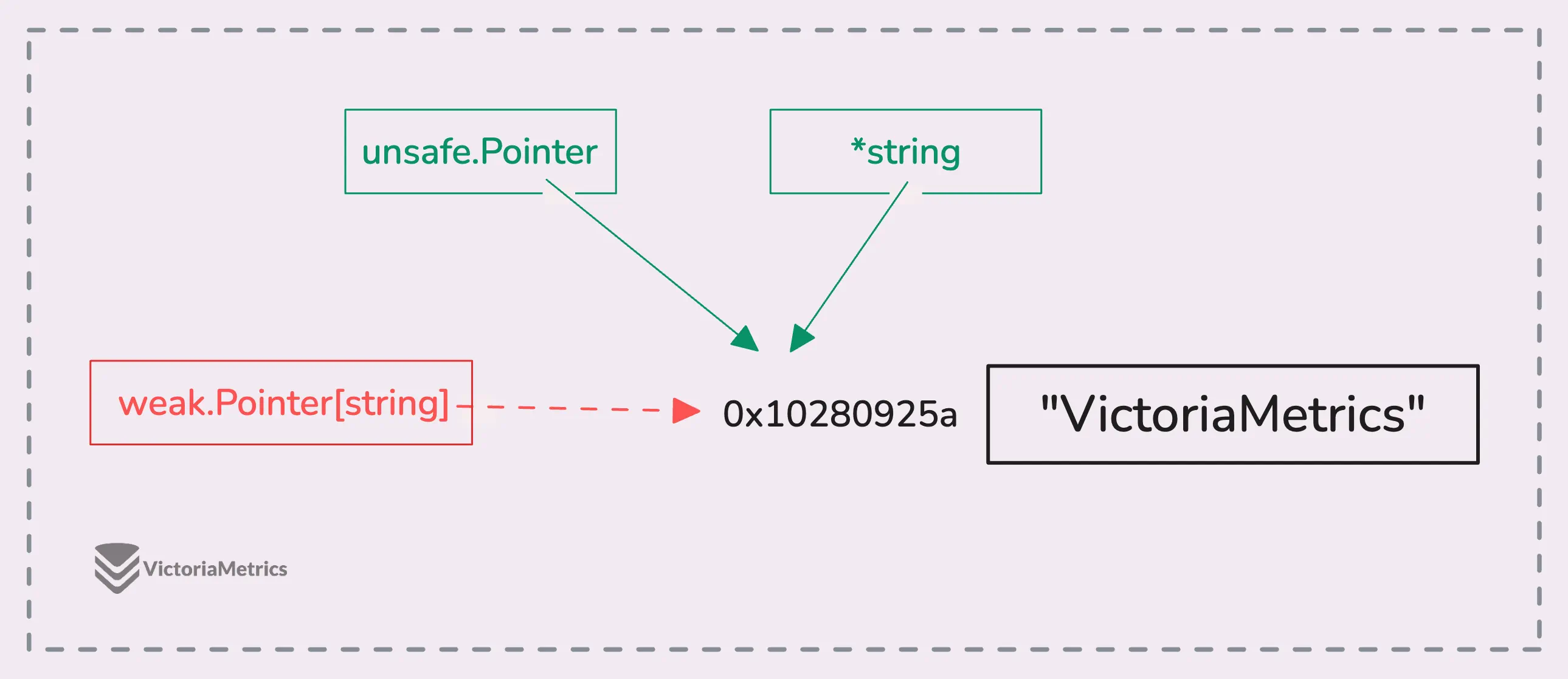

Before diving into the internal of the unique package, there’s a new concept worth mentioning: the “weak pointer.” This is a fresh addition to Go (at least at the time I’m writing this), and it changes the way we handle references in memory.

What is Weak Pointer?

#

Normally, when you’ve got a pointer to something, the garbage collector (GC) treats that object as “in use,” meaning it won’t be freed.

A weak pointer (or weak reference) works differently, as it’s a reference to a memory object that doesn’t stop the GC from freeing that memory. But, you can convert it back into a regular (strong) pointer if you need to hold onto it.

In other words, with a weak pointer, the memory can still be collected by the GC if no strong references (normal pointers) are holding onto it.

“But what’s the real use case for this?”

In the Go proposal by Michael Knyszek, weak pointers are designed for cases where you need a reference to an object but don’t want to control how long that object lives. If later you decide, “Actually, I do need this to stick around,” you can convert that weak pointer into a strong pointer.

But the beauty of weak pointers is that they’re “non-intrusive”, they don’t manage the memory themselves.

“Okay, but how do we know when the memory is no longer valid?”

Great point.

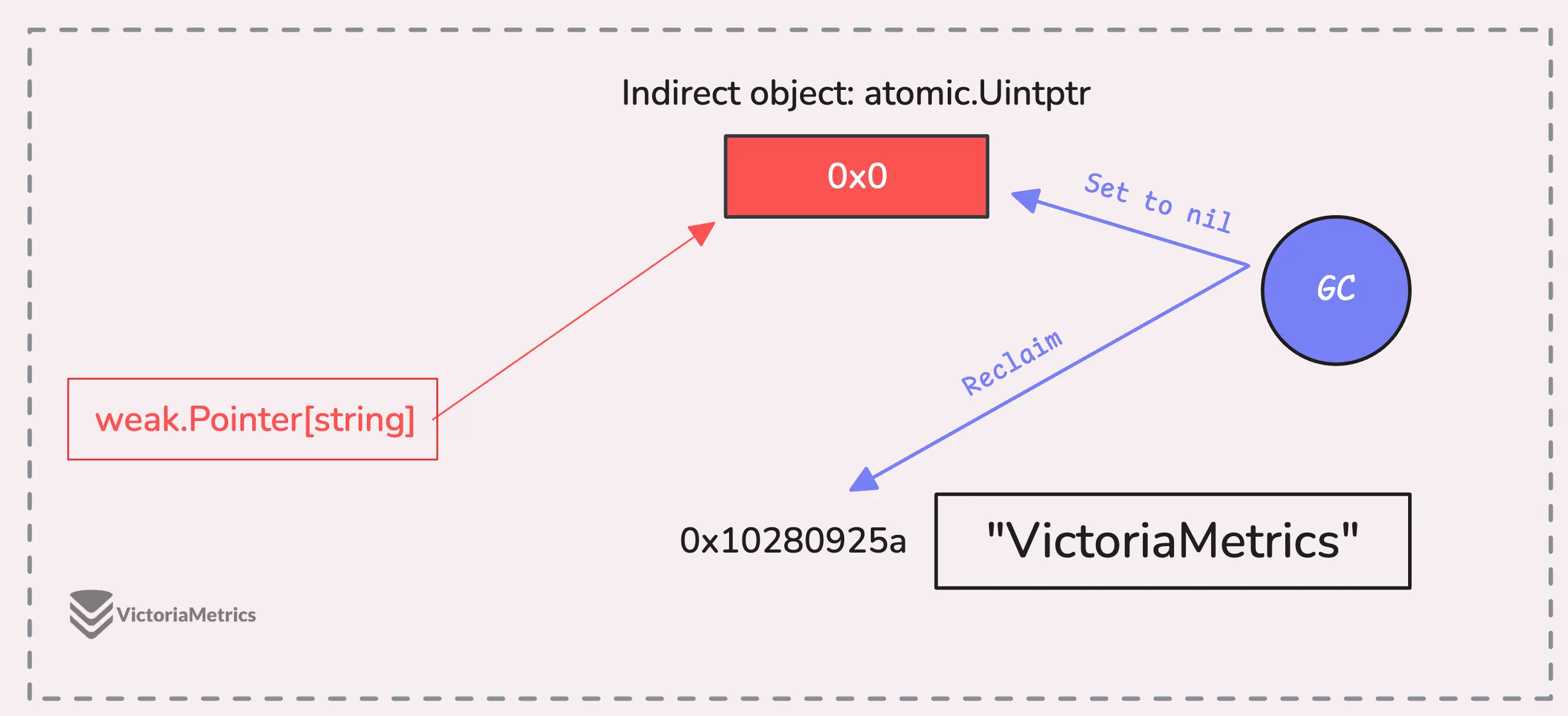

When the GC decides it’s time to free up the memory for an object, it just updates the weak pointer to nil. The catch is that weak pointers can become nil without you realizing it.

So, every time you want to use a weak pointer, you first have to check whether it’s still valid (i.e., not nil). If it’s nil, the memory is gone, and we’re out of luck.

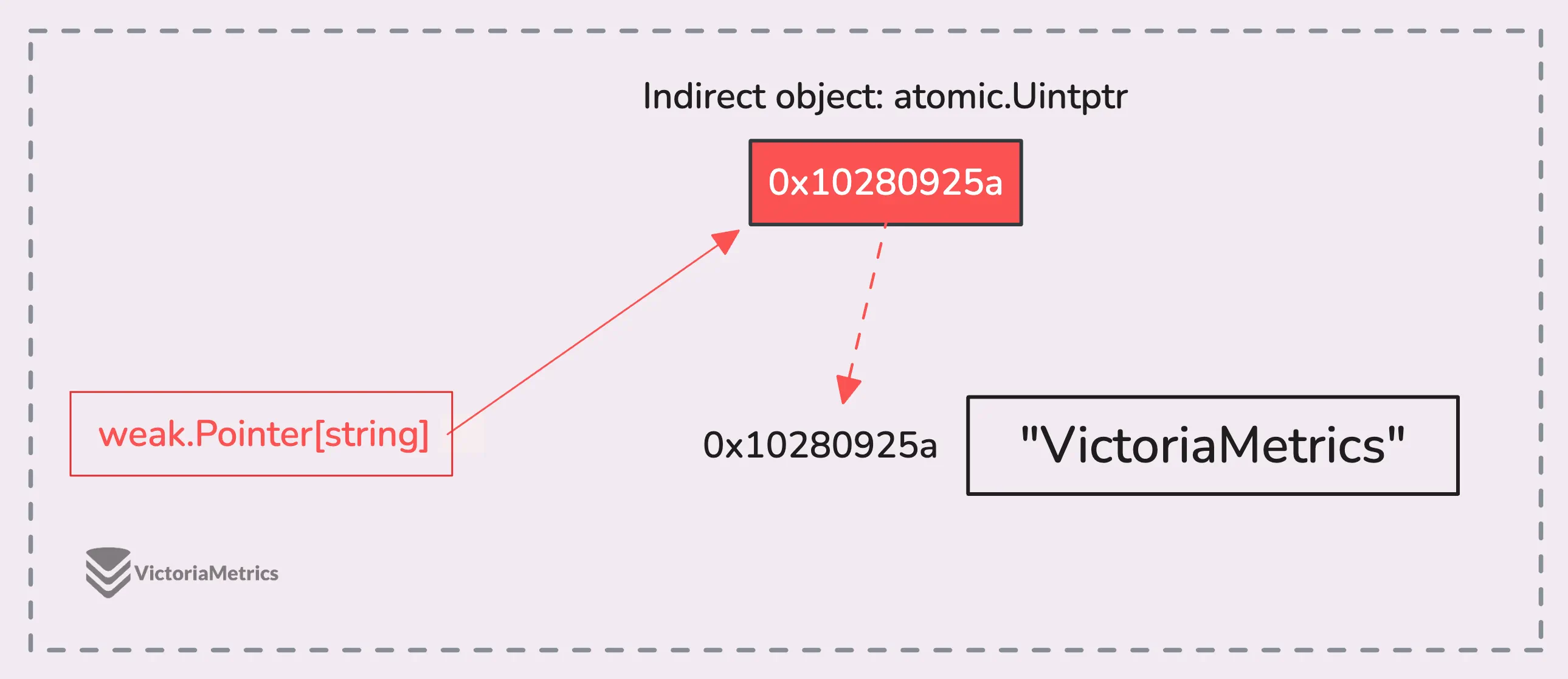

Interestingly, a weak pointer doesn’t actually point directly to the object in memory. Instead, it points to what’s called an “indirection object,” which is like a middleman of type atomic.Uintptr (correct me). This indirection object is just a small 8-byte block of memory that contains a memory address to the actual memory being referenced.

The reason for this indirection layer is efficiency.

When the GC frees the memory for an object, it only needs to update this one pointer inside the indirection object. This way, all weak pointers referencing that memory get set to nil instantly, without any extra work.

It speeds up the whole process since the GC doesn’t have to go through and manually clear each weak pointer individually.

The concept of weak pointers has been internal for a while, but recently the Go team accepted a proposal “weak: new package providing weak pointers” by Michael Knyszek to make it part of the public API.

A Global Tree Map

#

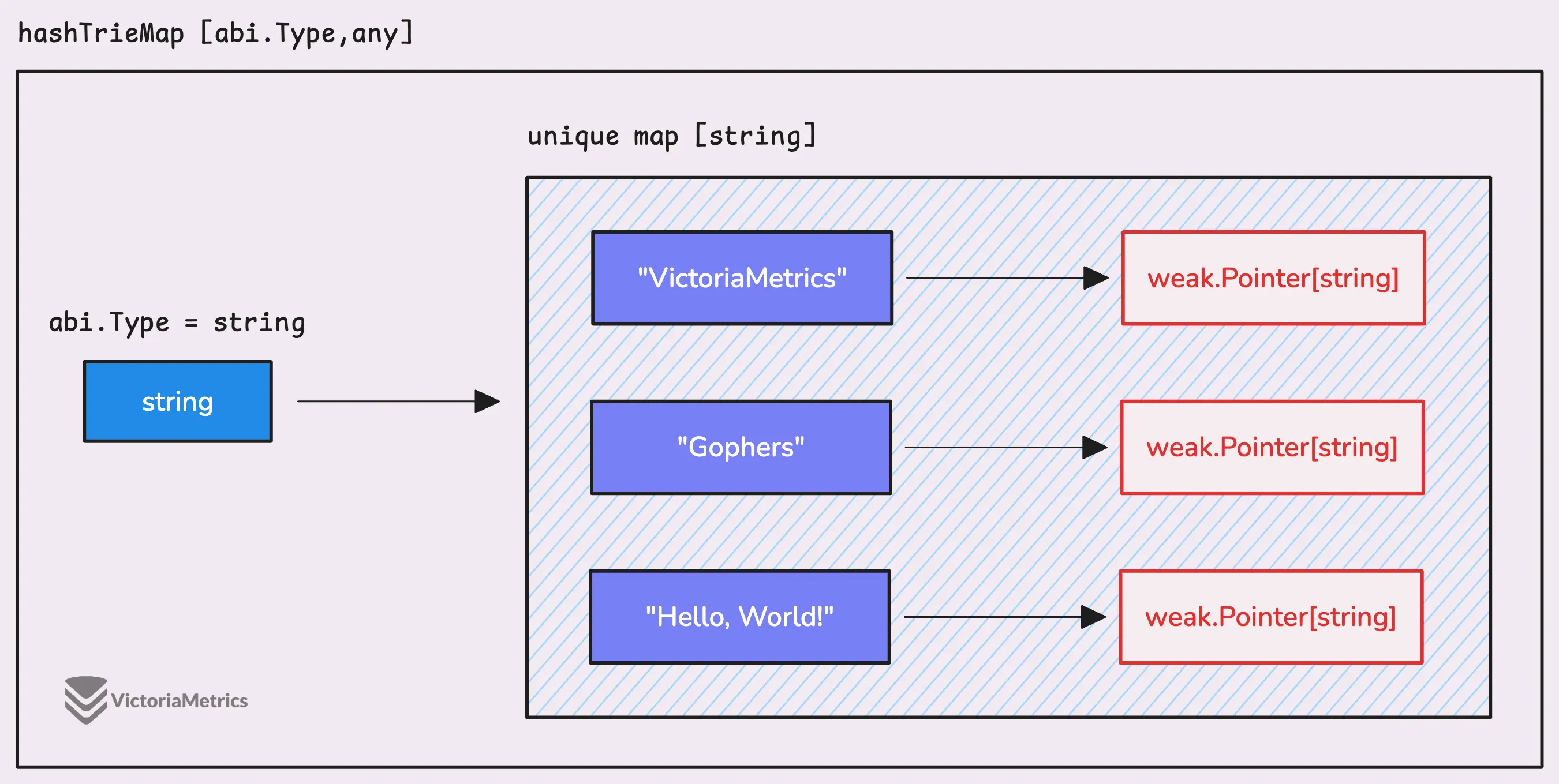

To handle deduplication across different types, there’s a global map of maps called uniqueMaps:

var uniqueMaps = concurrent.NewHashTrieMap[*abi.Type, any]() // any is always a *uniqueMap[T]."

Even though the value type of uniqueMaps is listed as any, under the hood, it’s always going to be a *uniqueMap[T]. So what we’ve actually got here is a two-level structure designed to manage canonical values, organized by their type.

At the top level, uniqueMaps is a hash-trie map where the keys represent specific types (*abi.Type). The value for each type key is another map, specifically a *uniqueMap[T], which is also a hash-trie map (HashTrieMap). This inner map holds the canonicalized values for that particular type. The key for this inner map is the value itself, while the value is a weak pointer to the interned object.

So instead of having one massive map storing values of every type, each type gets its own map to keep everything tidy.

“Wait, what exactly is a HashTrieMap?”

We won’t dive too deep into the technical details here, but let’s give a quick overview.

A hash-trie is a mix between a hash table and a trie (also known as a prefix tree). It works by taking the key, hashing it, and then using pieces of the hash to navigate through the trie’s structure. At each level, the trie branches out based on bits of the hash.

The map is made up of two types of nodes:

- Indirect nodes: These are the internal nodes of the trie and each one contains an array of child pointers, and the branching is based on bits from the hash of the key.

- Entry nodes: These are the leaf nodes where the actual key-value pairs live.

If two keys happen to hash to the same value, they’re placed in an overflow list attached to the entry node. When you look up a key, this overflow list gets scanned to find the right match.

Now that we’ve got the structure sorted, let’s dive into the most commonly used API in this package, Make[T comparable](value T) Handle[T].

Make[T comparable](value T) Handle[T]

#

When we call the Make() function, it’s going to look for a unique map that corresponds to the type T. To figure out the value’s type, Go uses an internal type called abi.Type.

If this is the first time you’re calling Make() for that particular type, the map won’t exist yet.

In that case, the function creates a new map and sets up a background cleanup process to make sure the map doesn’t hold onto values that are no longer needed (we’ll cover the cleanup process later).

Since multiple goroutines might try to create the same map at the same time, the hash-trie map is designed to be concurrency-safe. So, whichever goroutine manages to create the map first wins the race, and all the others will just use that same map.

func Make[T comparable](value T) Handle[T] {

// Find the map for type T.

typ := abi.TypeFor[T]()

ma, ok := uniqueMaps.Load(typ)

if !ok {

setupMake.Do(registerCleanup)

ma = addUniqueMap[T](typ)

}

m := ma.(*uniqueMap[T])

...

}

Once we’ve got the map, if the value we’re passing in has already been stored, it retrieves the existing canonical version. If the value doesn’t exist yet, we create a new clone of the value and store it in the map.

“But why do we need to clone the value?”

Remember we talked about this earlier, when you take a substring or a slice of a string, that new string still references the original, larger byte array in memory.

Even if the new string is tiny, the entire original big string (or byte array) sticks around as long as any part of it is still being referenced.

Since our unique map uses the value as the key, if we don’t clone the value, we might end up holding onto a lot more memory than we actually need. You could be stuck with a small key holding onto a massive chunk of memory.

In fact, this exact problem has been pointed out before.

Valentin Deleplace, the author of the article Interning in Go we mentioned earlier, raised an issue about this. He found that even after interning just a small substring, the original large string was still hanging around in memory.

And the reason? The Make() function did clone the value, but unintentionally used the original value as the key of the unique map.

Now, after either retrieving or inserting the value into the map, the function then tries to convert the weak pointer back into a strong pointer to make sure the value is still valid (i.e., it hasn’t been garbage-collected yet). If the pointer turns out to be nil, it means the memory has been reclaimed.

func Make[T comparable](value T) Handle[T] {

...

var (

toInsert *T // Pointer to the key

toInsertWeak weak.Pointer[T] // The value to insert

)

newValue := func() (T, weak.Pointer[T]) {

if toInsert == nil {

toInsert = new(T)

*toInsert = clone(value, &m.cloneSeq)

toInsertWeak = weak.Make(toInsert)

}

return *toInsert, toInsertWeak

}

var ptr *T

for {

// Check the map.

wp, ok := m.Load(value)

if !ok {

// Try to insert a new value into the map.

k, v := newValue()

wp, _ = m.LoadOrStore(k, v)

}

// Now that we're sure there's a value in the map, let's

// try to get the pointer we need out of it.

ptr = wp.Strong()

if ptr != nil {

break

}

// The weak pointer is nil, so the old value is truly dead.

// Try to remove it and start over.

m.CompareAndDelete(value, wp)

}

runtime.KeepAlive(toInsert)

return Handle[T]{ptr}

}

In that case, the function removes the old entry from the map and starts fresh, trying to store a new version of the value.

Once everything’s set and the value has been successfully retrieved or created, the function returns a Handle[T] that wraps a pointer to the canonical version of the value (return Handle[T]{ptr}).

This Handle[T] can now be used for comparisons or managing the value, without ever having to compare the actual content of the value itself.

To sum up, the process of using Make() is as follows:

“But when exactly does the weak pointer become nil? Or when does the key become invalid?”

Good question! The weak pointer becomes nil or technically, the indirect object it points to holds a nil memory address, when there’s no Handle or other objects left referencing the memory managed by that Handle, and the garbage collector (GC) steps in and does its job. As soon as the GC notices that nothing’s holding onto that memory anymore, it marks the weak pointer as nil, and the value is freed up.

We’ll dive into this topic in the next section.

Cleanup

#

Now, let’s talk about cleanup, because if we don’t have a way to tidy up the map, we’re back to that unbounded memory growth problem we mentioned earlier. So how does the system know when it’s time to remove a value from the map?

Well, the unique package is backed by the Go team and supported by the Go runtime’s garbage collector (GC).

When you call Make() for the first time, it registers a cleanup process with the GC. It’s basically saying, “Hey, whenever you kick off your marking phase for objects, give me a heads-up!” If you’ve ever read about Go’s sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It, you’ll recognize a similar pattern here.

So, when the GC starts its marking phase, it sends that notification to the global maps.

The cleanup process then runs through each unique map (remember, there’s a separate map for each type), and it removes any entries where the weak references have gone nil.

A final note: this automatic garbage collection, which cleans up the map, could be a potential hurdle when deciding whether to use the interning feature introduced in Go 1.23.

The issue is that you don’t have direct control over how long an object sticks around. The only workaround is adjusting the GOGC value to delay the garbage collection process, but that affects your entire application just to achieve this one optimization. If you set a low GOGC value, you might run into problems where the values get swept away too soon.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- Go Sync Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus