- Blog /

- Monotonic and Wall Clock Time in the Go time package

Monotonic and Wall Clock Time in the Go time package

Modern operating systems usually keep track of two kinds of clocks: a wall clock and a monotonic clock.

The wall clock is the “real-world” clock that shows calendar dates and times, like UTC or your local time. This clock can be adjusted for synchronization (for example, using NTP) or manually changed by system administrators. It can also suddenly jump due to daylight saving time or leap seconds.

Note

NTP (Network Time Protocol) is a standard internet protocol that allows computers to exchange timestamps. Computers use NTP to synchronize their clocks to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). Over the public internet, NTP usually achieves accuracy within a few milliseconds, and on fast local networks, it can be accurate to less than one millisecond.

Since wall clocks can jump forward or backward, slow down, or speed up, measuring time intervals directly using the wall clock can cause errors. For example, syncing time using NTP might slightly speed up or slow down the clock, or inserting a leap second can cause the same second to repeat, etc.

Before Go version 1.9, the time API only used wall-clock time. This created bugs when the clock was adjusted. A famous example was a leap-second bug that caused a Cloudflare outage in 2016.

To fix these issues, operating systems also use a second type of clock: a monotonic clock. This clock never goes backward. It only moves forward steadily and cannot be manually adjusted.

Because each clock behaves differently, they have separate purposes:

- Wall clocks are for “telling time” (giving timestamps that have meaning globally).

- Monotonic clocks are for reliably “measuring time intervals.”

Go follows this same approach.

Monotonic Clock

#

In Go, when you call time.Now(), the function returns a time.Time struct representing the current moment. This struct actually holds two different values: the wall clock time and an (optional) monotonic clock reading.

The monotonic part is stored internally in the ext field of the time.Time struct. You can’t access this directly through Go’s public API — it’s only used behind the scenes.

Since the monotonic reading is tied specifically to your current process and system uptime, it has no real meaning outside your running program. That’s why, when you serialize a time.Time, the monotonic component isn’t included.

But you may notice during debugging that printing a time.Time struct gives you an extra suffix like m=+0.000123456:

func main() {

now := time.Now()

fmt.Println(now) // 2024-11-10 23:00:00 +0000 UTC m=+0.001219709

}

That m= value shows the monotonic clock offset (in seconds) at the exact moment your time.Time was captured. In the example above, this means 0.001219709 seconds passed since the program started running.

When your Go program starts, it notes the current operating system’s monotonic clock value. Each time you call time.Now(), Go calculates how much time has passed since your program began. This is what the hidden monotonic field shows: elapsed nanoseconds since your process started, not since your machine booted.

Common Mistakes

#

The monotonic clock in time.Time is optional. A time.Time value only includes a monotonic reading when it is created directly by the runtime.

This happens in exactly one place: when you call time.Now(). Other ways to construct a time.Time value, such as time.Date, time.Unix, time.Parse, or any unmarshaling function, never set the monotonic flag.

These only set the wall-clock time:

func main() {

now := time.Now()

fmt.Println(now)

fmt.Println(now.UTC())

fmt.Println(now.Truncate(0))

fmt.Println(time.Date(2025, 7, 13, 0, 0, 0, 0, time.UTC))

}

// Output:

// 2025-07-13 12:14:36.707899 +0000 UTC m=+0.000080168

// 2025-07-13 12:14:36.707899 +0000 UTC

// 2025-07-13 12:14:36.707899 +0000 UTC

// 2025-07-13 00:00:00 +0000 UTC

You can see that the last three timers do not have the m= prefix.

Note

The example above assumes your location uses the UTC timezone. To get the same output, set your system timezone to UTC if needed:

func init() {

os.Setenv("TZ", "UTC")

}

Comparing Two time.Time Values

#

A common mistake is comparing time.Time values using the equality operator:

func main() {

now := time.Now()

nowUTC := now.UTC()

nowTruncated := now.Truncate(0)

fmt.Println(now == nowUTC) // false

fmt.Println(now == nowTruncated) // false

fmt.Println(nowUTC == nowTruncated) // false

}

There are two problems with this. First, when you call now.UTC() or now.Truncate(0), these methods deliberately remove the monotonic part from the original value. That’s why now != nowTruncated.

Second, and more confusing, even though both now.UTC() and now.Truncate(0) strip the monotonic reading, comparing them with == still returns false. This is because the time.Time struct contains a pointer to represent the location (*time.Location). The UTC() method not only removes the monotonic part but also sets the location pointer to nil. The Truncate(0) call does not change the location pointer.

To compare two time.Time values correctly, use the Equal method instead:

fmt.Println(now.Equal(nowUTC)) // true

fmt.Println(now.Equal(nowTruncated)) // true

fmt.Println(nowUTC.Equal(nowTruncated)) // true

Everything now works as you would expect. The Equal method has two paths for checking:

- If both

time.Timevalues have a monotonic reading, Go compares their monotonic clocks. - If they do not, Go compares the wall-clock values, including the seconds and the nanoseconds.

func (t Time) Equal(u Time) bool {

// monotonic clock check

if t.wall&u.wall&hasMonotonic != 0 {

return t.ext == u.ext

}

// wall clock check

return t.sec() == u.sec() && t.nsec() == u.nsec()

}

Use Wall Clock To Measure Time

#

As we discussed, functions like time.Date, time.Unix, and time.Parse create time.Time values with only the wall-clock fields. These constructors never attach a monotonic reading, because they do not query the runtime’s monotonic counter.

Only time.Now (and a few helpers that call it internally) fetch the monotonic counter and store it inside the value. When you use operations that do not change the instant itself (such as Add, AddDate, Sub, Round, Truncate, or simple arithmetic with Duration), Go will carry the monotonic part forward if it was there to begin with.

For example, time.Since is just a shortcut for time.Now().Sub(t). It will use the monotonic clock if your time.Time value contains it:

package time

func Since(t Time) Duration {

if t.wall&hasMonotonic != 0 {

return subMono(runtimeNano()-startNano, t.ext)

}

return Now().Sub(t)

}

If you use time.Since with a time.Time value that does not have the monotonic clock, you can run into problems:

// parse the time (wall clock only, no monotonic)

lastModified, _ := time.Parse(http.TimeFormat, rawHeader)

// lastModified lacks monotonic data, so Since falls back to wall clock math

ago := time.Since(lastModified)

The problem is, the system’s wall clock might not be accurate and can be adjusted. This means ago might not represent the real duration between lastModified and now.

Performance Trick

There is a performance trick when you have an ultra-hot path that needs the current wall-clock time.

Instead of using time.Now(), you can use another time.Time value that has a monotonic clock to calculate the current time:

past := time.Now()

...

past.Add(time.Since(past))

This can give you up to 1.5x better performance (50% faster). However, the trade-off is that it won’t catch any clock adjustments, as it calculates the current time using the monotonic clock (fast path). Otherwise, use the clearer time.Now().

(Source: Aliaksandr Valialkin)

Schedule Based on Monotonic Time

#

On the other hand, if your application cares about “what time is it right now?” or “what is the next wall-clock time to process?”, you need to use wall clock comparisons and be careful if the time can move backward.

For example, on some systems, when the machine goes to sleep or suspends, the monotonic clock usually pauses. When the system resumes, the monotonic clock continues from where it left off. This does not count the time spent sleeping.

Go’s design helps protect you from many timing bugs, especially those caused by wall clock jumps, by defaulting to monotonic time for measuring intervals and scheduling timers (like time.NewTicker, time.Sleep, and others). This is almost always the right behavior — unless you really need to schedule things based on the wall clock, as people see it, regardless of any time jumps. This comes up in cron jobs, log rotation, alert checks, and other jobs that must follow the calendar clock.

Note

There was a real production issue caused by the system time changing in vmalert (a VictoriaMetrics component that checks alert state in a time-based way). This was fixed in PR - Jun 20, 2025

How time.Time Looks Like

#

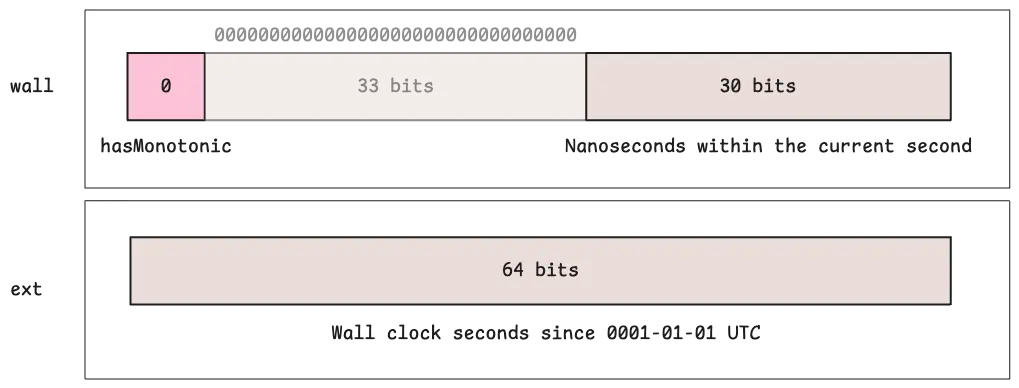

Before Go 1.9, the time.Time struct was simple:

type Time struct {

sec int64

nsec int32

loc *Location

}

Here, sec is a signed 64-bit count of seconds from the Go “internal” epoch (Jan 1 0001 00:00:00 UTC). nsec is a signed 32-bit count in the range [0, 1e9). Together they give 1‑ns resolution across a range of billions of years.

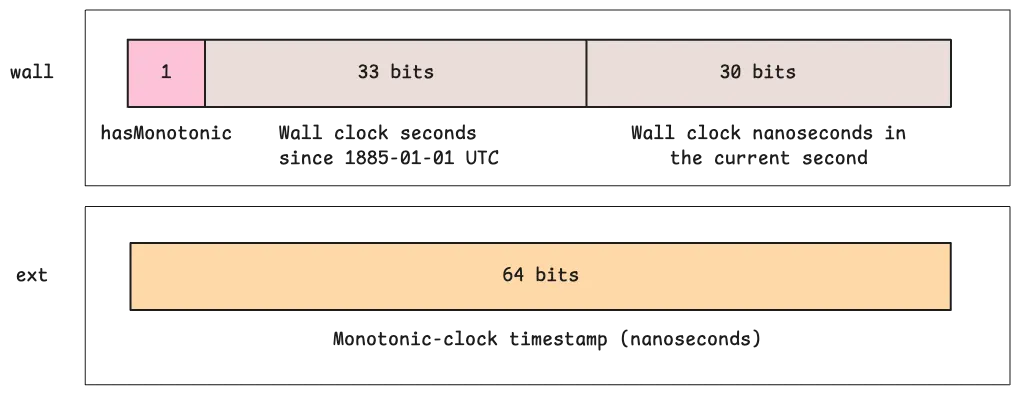

Go 1.9 introduced monotonic time to make measuring elapsed time safe against clock changes. From this version on, when you call time.Now(), the returned time.Time value can carry both a wall-clock timestamp and, optionally, a monotonic timestamp.

No matter the Go version, time.Time has always used 24 bytes of memory (two 64-bit words plus a pointer). When adding monotonic time in Go 1.9, the Go team kept this size the same:

type Time struct {

wall uint64

ext int64

loc *Location

}

Just from looking at this struct, you cannot see how both timestamps are stored. The answer comes from how Go evolved its time layout.

To fit both numbers in 128 bits, Go changed the layout. When there is no monotonic timestamp, ext can use all its 64 bits to store wall-clock seconds. This gives an enormous range—about ±292 billion years.

When a monotonic timestamp is stored, ext is used for the monotonic seconds instead. In this case, wall seconds move into the wall word.

To do this, Go uses the 33 bits in wall that were not needed before to represent wall-clock seconds. This covers the years 1885 to 2157, which is enough for practical dates. The 30 low bits of wall still store nanoseconds as before.

But what happens if a time.Time carries a monotonic clock, but its wall-clock date falls outside the 1885–2157 range?

You can see this behavior in the time.Add() method, which normally does not strip the monotonic clock. It adds the duration to both the wall and monotonic clocks:

func (t Time) Add(d Duration) Time {

...

if t.wall&hasMonotonic != 0 {

te := t.ext + int64(d)

if d < 0 && te > t.ext || d > 0 && te < t.ext {

// Monotonic clock reading now out of range; degrade to wall-only.

t.stripMono()

} else {

t.ext = te

}

}

return t

}

However, when the wall clock falls outside the valid range, Go silently strips the monotonic data. All this juggling is hidden from users of time.Time. It just works, but understanding this trick can help you know what is happening under the hood.

Most of the time, this works fine. But when our application scales across many different machines and scenarios, we need to consider edge cases and understand how everything works.

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem. If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus