- Blog /

- Go sync.WaitGroup and The Alignment Problem

Go sync.WaitGroup and The Alignment Problem

This post is part of a series about handling concurrency in Go:

- Go sync.Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- Go sync.WaitGroup and The Alignment Problem (We’re here)

- Go sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It

- Go sync.Cond, the Most Overlooked Sync Mechanism

- Go sync.Map: The Right Tool for the Right Job

- Go Sync.Once is Simple… Does It Really?

- Go Singleflight Melts in Your Code, Not in Your DB

WaitGroup is basically a way to wait for several goroutines to finish their work.

Each of sync primitives has its own set of problems, and this one’s no different. We’re going to focus on the alignment issues with WaitGroup, which is why its internal structure has changed across different versions.

This article is based on Go 1.23. If anything changes down the line, feel free to let me know through X(@func25).

What is sync.WaitGroup?

#

If you’re already familiar with sync.WaitGroup, feel free to skip ahead.

Let’s dive into the problem first, imagine you’ve got a big job on your hands, so you decide to break it down into smaller tasks that can run simultaneously, without depending on each other.

To handle this, we use goroutines because they let these smaller tasks run concurrently:

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go func(i int) {

fmt.Println("Task", i)

}(i)

}

fmt.Println("Done")

}

// Output:

// Done

But here’s the thing, there’s a good chance that the main goroutine finishes up and exits before the other goroutines are done with their work.

When we’re spinning off many goroutines to do their thing, we want to keep track of them so that the main goroutine doesn’t just finish up and exit before everyone else is done. That’s where the WaitGroup comes in. Each time one of our goroutines wraps up its task, it lets the WaitGroup know.

Once all the goroutines have checked in as ‘done,’ the main goroutine knows it’s safe to finish, and everything wraps up neatly.

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(10)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go func(i int) {

defer wg.Done()

fmt.Println("Task", i)

}(i)

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Done")

}

// Output:

// Task 0

// Task 1

// Task 2

// Task 3

// Task 4

// Task 5

// Task 6

// Task 7

// Task 8

// Task 9

// Done

So, here’s how it typically goes:

- Adding goroutines: Before starting your goroutines, you tell the WaitGroup how many to expect. You do this with WaitGroup.Add(n), where n is the number of goroutines you’re planning to run.

- Goroutines running: Each goroutine goes off and does its thing. When it’s done, it should let the WaitGroup know by calling

WaitGroup.Done()to reduce the counter by one. - Waiting for all goroutines: In the main goroutine, the one not doing the heavy lifting, you call

WaitGroup.Wait(). This pauses the main goroutine until that counter in the WaitGroup reaches zero. In plain terms, it waits until all the other goroutines have finished and signaled they’re done.

Usually, you’ll see WaitGroup.Add(1) being used when firing up a goroutine:

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

...

}()

}

Both ways are technically fine, but using wg.Add(1) has a small performance hit. Still, it’s less error-prone compared to using wg.Add(n).

“Why is

wg.Add(n)considered error-prone?”

The point is this, if the logic of the loop changes down the road, like if someone adds a continue statement that skips certain iterations, things can get messy:

wg.Add(10)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

if someCondition(i) {

continue

}

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

...

}()

}

In this example, we’re using wg.Add(n) before the loop, assuming the loop will always start exactly n goroutines.

But if that assumption doesn’t hold, like if some iterations get skipped, your program might get stuck waiting for goroutines that were never started. And let’s be honest, that’s the kind of bug that can be a real pain to track down.

In this case, wg.Add(1) is more suitable. It might come with a tiny bit of performance overhead, but it’s a lot better than dealing with the human error overhead.

There’s also a pretty common mistake people make when using sync.WaitGroup:

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go func() {

wg.Add(1)

defer wg.Done()

...

}()

}

Here’s what it comes down to, wg.Add(1) is being called inside the goroutine. This can be an issue because the goroutine might start running after the main goroutine has already called wg.Wait().

That can cause all sorts of timing problems. Also, if you notice, all the examples above use defer with wg.Done(). It indeed should be used with defer to avoid issues with multiple return paths or panic recovery, making sure that it always gets called and doesn’t block the caller indefinitely.

That should cover all the basics.

How sync.WaitGroup Looks Like?

#

Let’s start by checking out the source code of sync.WaitGroup. You’ll notice a similar pattern in sync.Mutex.

Again, if you’re not familiar with how a mutex works, I strongly suggest you check out this article first: Go Sync Mutex: Normal & Starvation Mode.

type WaitGroup struct {

noCopy noCopy

state atomic.Uint64

sema uint32

}

type noCopy struct{}

func (*noCopy) Lock() {}

func (*noCopy) Unlock() {}

In Go, it’s easy to copy a struct by just assigning it to another variable. But some structs, like WaitGroup, really shouldn’t be copied.

Copying a WaitGroup can mess things up because the internal state that tracks the goroutines and their synchronization can get out of sync between the copies. If you’ve read the mutex post, you’ll get the idea, imagine what could go wrong if we copied the internal state of a mutex.

The same kind of issues can happen with WaitGroup.

noCopy

#

The noCopy struct is included in WaitGroup as a way to help prevent copying mistakes, not by throwing errors, but by serving as a warning. It was contributed by Aliaksandr Valialkin, CTO of VictoriaMetrics, and was introduced in change #22015.

The noCopy struct doesn’t actually affect how your program runs. Instead, it acts as a marker that tools like go vet can pick up on to detect when a struct has been copied in a way that it shouldn’t be.

type noCopy struct{}

func (*noCopy) Lock() {}

func (*noCopy) Unlock() {}

Its structure is super simple:

- It has no fields, so it doesn’t take up any meaningful space in memory.

- It has two methods, Lock and Unlock, which do nothing (no-op). These methods are there just to work with the -copylocks checker in the go vet tool.

When you run go vet on your code, it checks to see if any structs with a noCopy field, like WaitGroup, have been copied in a way that could cause issues.

It will throw an error to let you know there might be a problem. This gives you a heads-up to fix it before it turns into a bug:

func main() {

var a sync.WaitGroup

b := a

fmt.Println(a, b)

}

// go vet:

// assignment copies lock value to b: sync.WaitGroup contains sync.noCopy

// call of fmt.Println copies lock value: sync.WaitGroup contains sync.noCopy

// call of fmt.Println copies lock value: sync.WaitGroup contains sync.noCopy

In this case, go vet will warn you about 3 different spots where the copying happens. You can try it yourself at: Go Playground.

Note that it’s purely a safeguard for when we’re writing and testing our code, we can still run it like normal.

Internal State

#

The state of a WaitGroup is stored in an atomic.Uint64 variable. You might have guessed this if you’ve read the mutex post, there are several things packed into this single value.

Here’s how it breaks down:

- Counter (high 32 bits): This part keeps track of the number of goroutines the WaitGroup is waiting for. When you call

wg.Add()with a positive value, it bumps up this counter, and when you callwg.Done(), it decreases the counter by one. - Waiter (low 32 bits): This tracks the number of goroutines currently waiting for that counter (the high 32 bits) to hit zero. Every time you call wg.Wait(), it increases this “waiter” count. Once the counter reaches zero, it releases all the goroutines that were waiting.

Then there’s the final field, sema uint32, which is an internal semaphore managed by the Go runtime.

when a goroutine calls wg.Wait() and the counter isn’t zero, it increases the waiter count and then blocks by calling runtime_Semacquire(&wg.sema). This function call puts the goroutine to sleep until it gets woken up by a corresponding runtime_Semrelease(&wg.sema) call.

We’ll dive deeper into this in another article, but for now, I want to focus on the alignment issues.

Alignment Problem

#

I know, talking about history might seem dull, especially when you just want to get to the point. But trust me, knowing the past is the best way to understand where we are now.

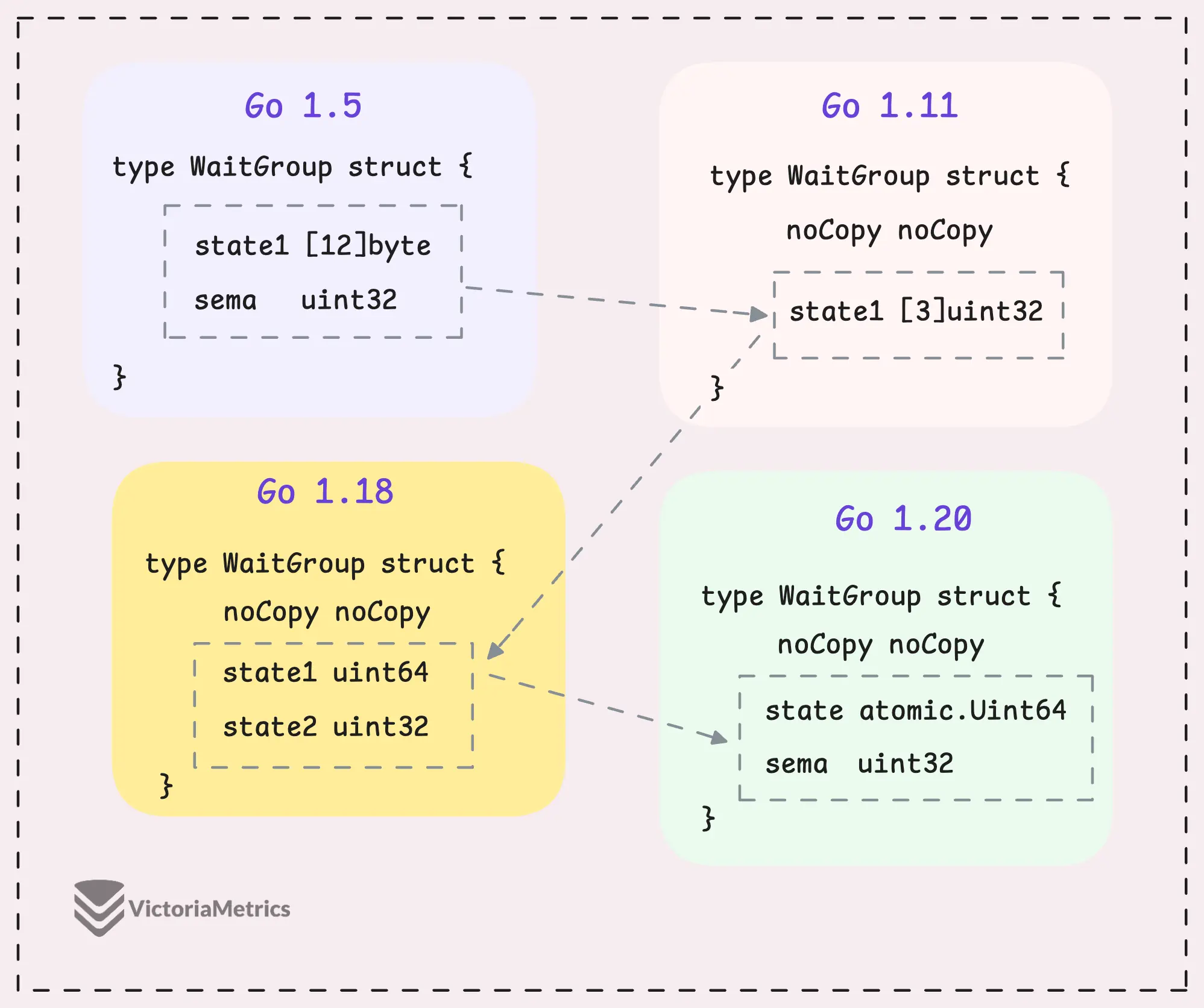

Let’s take a quick look at how WaitGroup has evolved over several Go versions:

I can tell you, the core of WaitGroup (the counter, waiter, and semaphore) hasn’t really changed across different Go versions. However, the way these elements are structured has been modified many times.

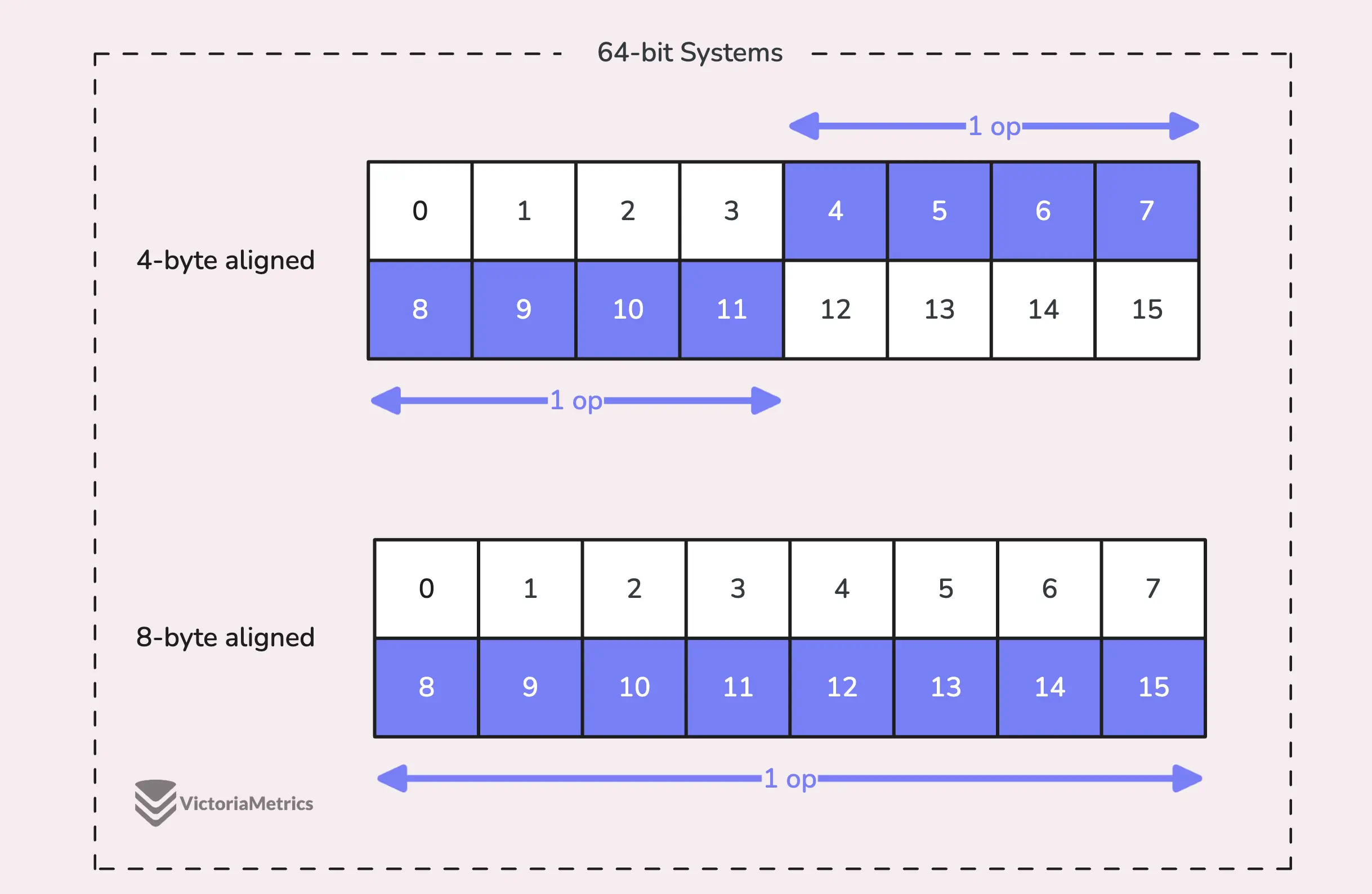

When we talk about alignment, we’re referring to the need for data types to be stored at specific memory addresses to allow for efficient access.

For example, on a 64-bit system, a 64-bit value like uint64 should ideally be stored at a memory address that’s a multiple of 8 bytes. The reason is, the CPU can grab aligned data in one go, but if the data isn’t aligned, it might take multiple operations to access it.

Things get tricky on 32-bit architectures, the compiler doesn’t guarantee that 64-bit values will be aligned on an 8-byte boundary. Instead, they might only be aligned on a 4-byte boundary.

This becomes a problem when we use the atomic package to perform operations on the state variable. The atomic package specifically notes:

“On ARM, 386, and 32-bit MIPS, it is the caller’s responsibility to arrange for 64-bit alignment of 64-bit words accessed atomically via the primitive atomic functions.”

Therefore, if we don’t align the state uint64 variable to an 8-byte boundary on these 32-bit architectures, it could cause the program to crash.

So, what’s the fix? Let’s take a look at how this has been handled across different versions.

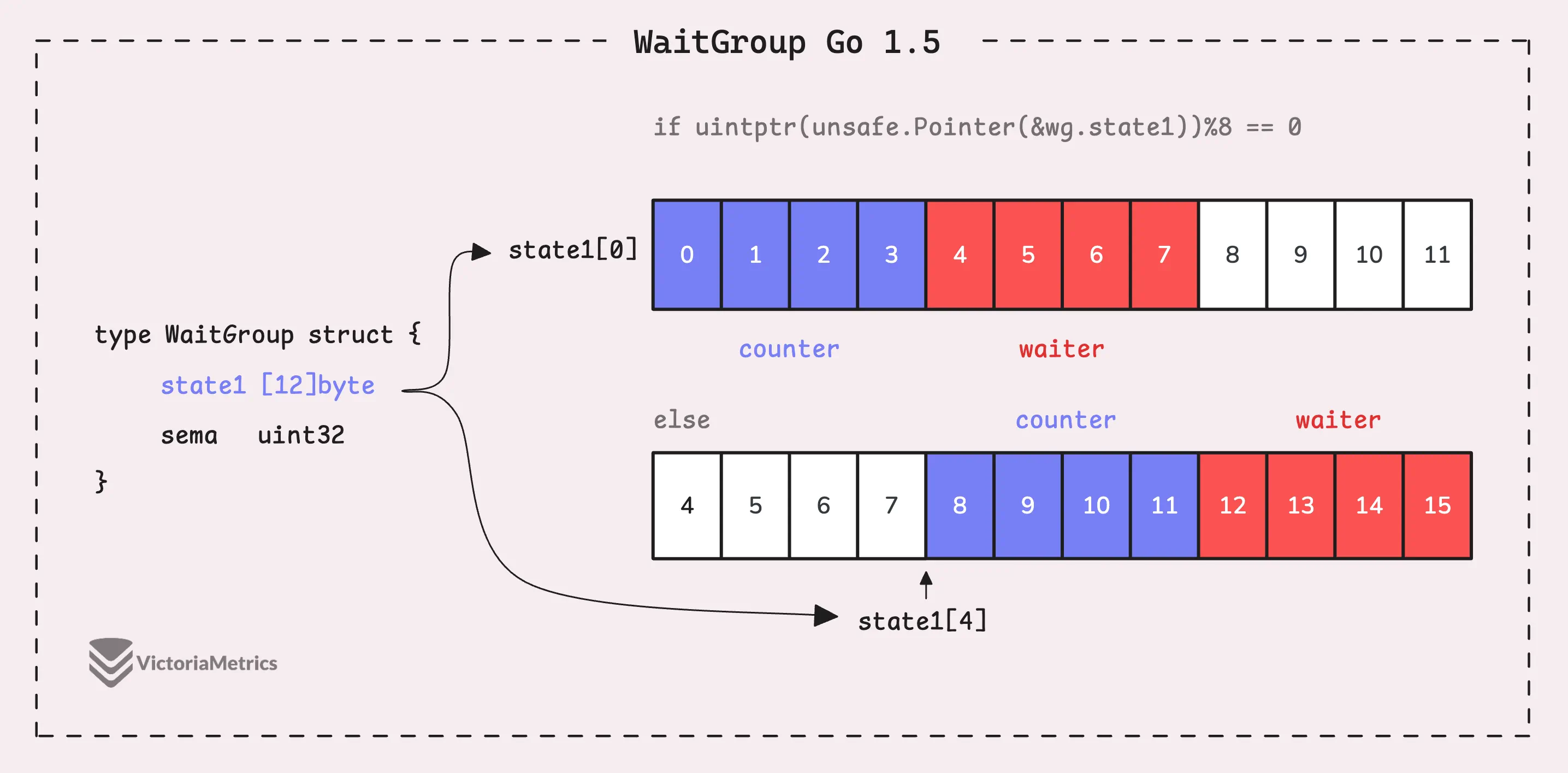

Go 1.5: state1 [12]byte

I’d recommend taking a moment to guess the underlying logic of this solution as you read the code below, then we’ll walk through it together.

type WaitGroup struct {

state1 [12]byte

sema uint32

}

func (wg *WaitGroup) state() *uint64 {

if uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1))%8 == 0 {

return (*uint64)(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1))

} else {

return (*uint64)(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1[4]))

}

}

Instead of directly using a uint64 for state, WaitGroup sets aside 12 bytes in an array (state1 [12]byte). This might seem like more than you’d need, but there’s a reason behind it.

The purpose of using 12 bytes is to ensure there’s enough room to find an 8-byte segment that’s properly aligned.

The alignment of the struct depends on its field’s type, so it is either 8-byte or 4-byte depending on the architecture. If the starting address of state1 isn’t aligned, the code can simply shift over by a few bytes (4 bytes in this case) to find a section within those 12 bytes that is.

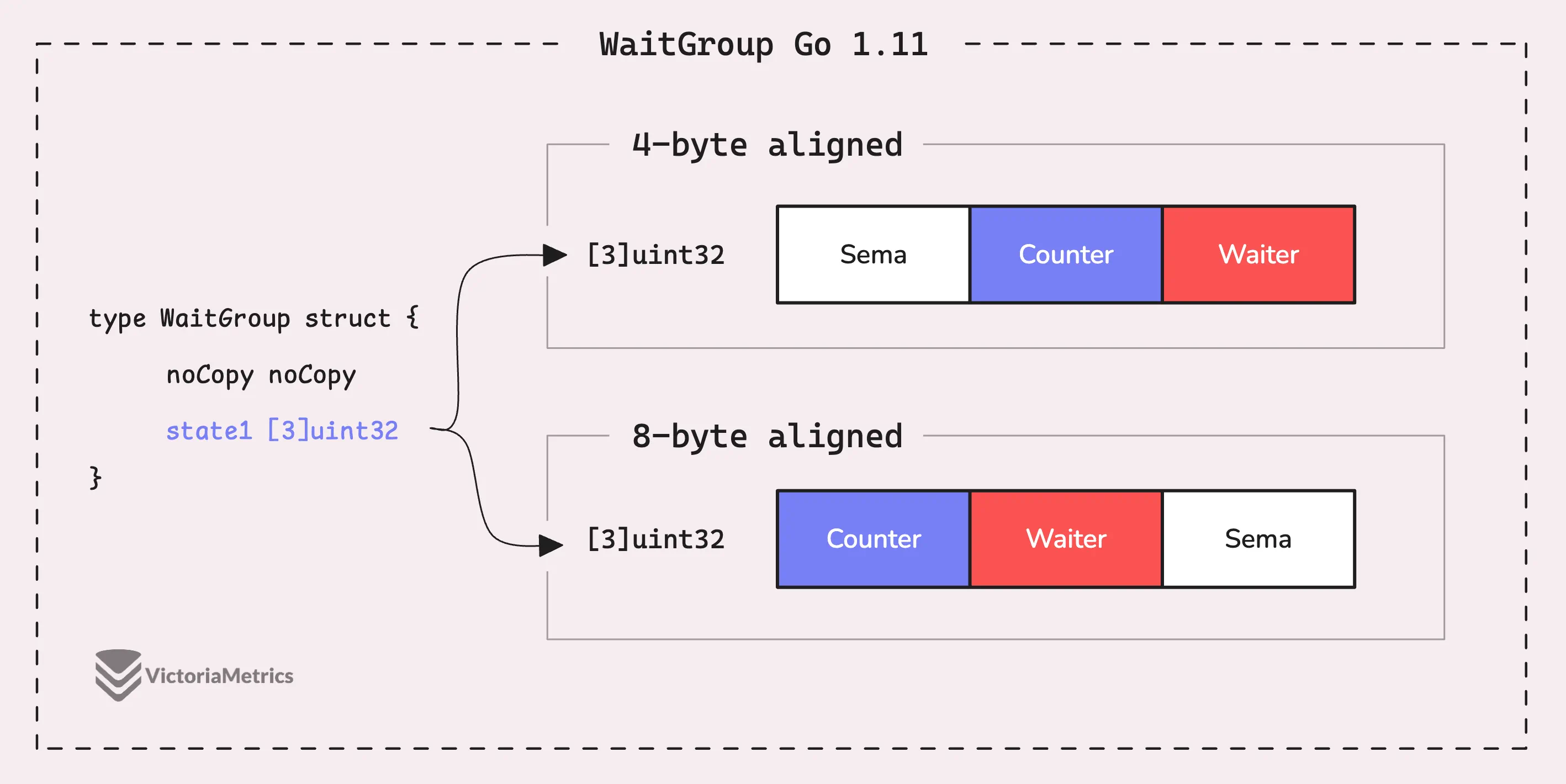

Go 1.11: state1 [3]uint32

Using 12 bytes was overkill, with 4 bytes essentially do nothing. In Go 1.11, the solution was to streamline things by merging the state (which includes the counter and waiter) and sema into just 3 uint32 fields.

type WaitGroup struct {

noCopy noCopy

state1 [3]uint32

}

// state returns pointers to the state and sema fields stored within wg.state1.

func (wg *WaitGroup) state() (statep *uint64, semap *uint32) {

if uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1))%8 == 0 {

return (*uint64)(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1)), &wg.state1[2]

} else {

return (*uint64)(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1[1])), &wg.state1[0]

}

}

So, how do we avoid the state alignment problem now? The answer lies in the state() method, but if you’re not familiar with the unsafe package, it might seem a bit tricky.

Since state1 is now an array of uint32, it starts at an address that’s a multiple of 4 bytes.

For an array type variable, its alignment matches the alignment of its element type.

Here’s how the state() method works if the address of wg.state1 isn’t 8-byte aligned:

- The first element (

state1[0]) is used for sema. - The second element (

state1[1]) is used to track the waiter count. - The third element (

state1[2]) is used for the counter.

And if the address of wg.state1 is 8-byte aligned, the elements in state1 are rearranged between state and sema as shown in the image above.

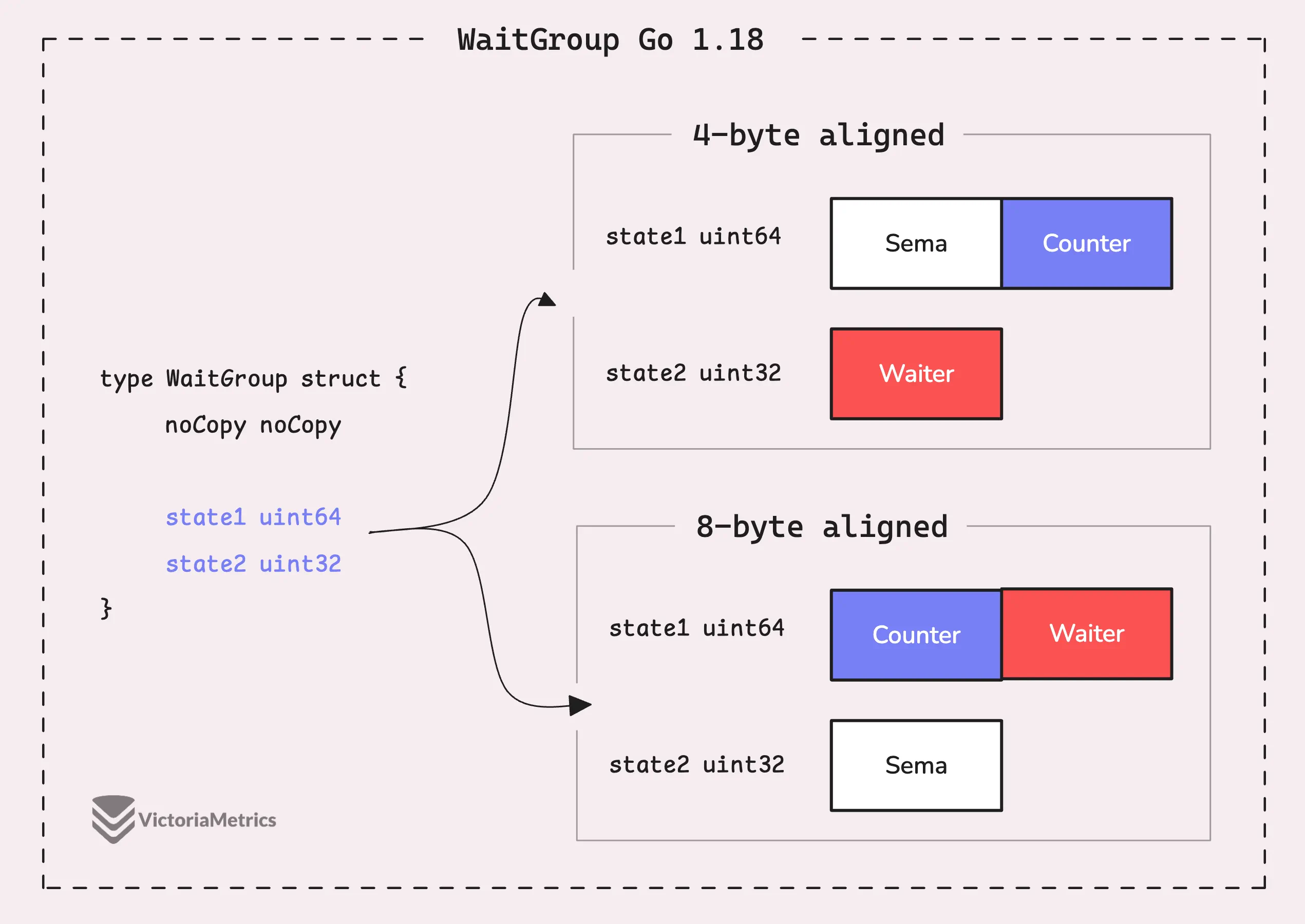

Go 1.18: state1 uint64; state2 uint32

The challenge with the previous approach was that whether we were dealing with 64-bit or 32-bit alignment, we still had to juggle the state and sema within a 12-byte array, right? But since most systems today are 64-bit, it made sense to optimize for the more common scenario.

The idea in Go 1.18 is simple: on a 64-bit system, we don’t need to do anything special, state1 holds the state, and state2 is for semaphore:

type WaitGroup struct {

noCopy noCopy

state1 uint64

state2 uint32

}

// state returns pointers to the state and sema fields stored within wg.state*.

func (wg *WaitGroup) state() (statep *uint64, semap *uint32) {

if unsafe.Alignof(wg.state1) == 8 || uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1))%8 == 0 {

// state1 is 64-bit aligned: nothing to do.

return &wg.state1, &wg.state2

} else {

state := (*[3]uint32)(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1))

return (*uint64)(unsafe.Pointer(&state[1])), &state[0]

}

}

However, on a system with 4-byte alignment, the code falls back to the previous Go 1.11 solution. The state() method converts state1 and state2 into a 3-element array of uint32 and rearranges the elements to keep the state and sema properly aligned.

The interesting part comes with Go 1.20, where they decided to use atomic.Uint64 to handle the state, completely removing the need for the state() method.

Go 1.20: state atomic.Uint64

In Go 1.19, a key optimization was introduced to ensure that uint64 values used in atomic operations are always aligned to 8-byte boundaries, even on 32-bit architectures.

To achieve this, Russ Cox introduced a special struct called atomic.Uint64, it’s basically a wrapper around uint64:

type Uint64 struct {

_ noCopy

_ align64

v uint64

}

// align64 may be added to structs that must be 64-bit aligned.

// This struct is recognized by a special case in the compiler

// and will not work if copied to any other package.

type align64 struct{}

So, what’s the deal with align64?

When you include align64 in a struct, it signals to the Go compiler that the entire struct needs to be aligned to an 8-byte boundary in memory.

“But how exactly does align64 pull this off?”

Well, align64 is just a plain, empty struct. It doesn’t have any methods or special behaviors like the noCopy struct we talked about earlier.

But here’s where the magic happens.

The align64 field itself doesn’t take up any space, but it acts as a “marker” that tells the Go compiler to handle the struct differently. The Go compiler recognizes align64 and automatically adjusts the struct’s memory layout with the necessary padding, making sure that the entire struct starts at an 8-byte boundary.

With this in place, the WaitGroup struct becomes much simpler:

type WaitGroup struct {

noCopy noCopy

state atomic.Uint64

sema uint32

}

Thanks to atomic.Uint64, the state is guaranteed to be 8-byte aligned, so you don’t have to worry about the alignment issues that could mess up atomic operations on 64-bit variables.

How sync.WaitGroup Internally Works

#

We’ve gone over the internal structure and the alignment issues with uint64 on 32-bit architectures, especially when dealing with atomic operations. But there’s one important question we haven’t resolved yet:

“Why don’t we just split the counter and waiter into two separate uint32 variables?”

That seems like it could simplify things, right?

If we used a mutex to manage concurrency, we wouldn’t have to worry about whether we’re on a 32-bit or 64-bit system, no alignment issues to deal with.

However, there’s a trade-off. Using locks, like a mutex, adds overhead, especially when operations are happening frequently. Every time you lock and unlock, you’re adding a bit of delay, which can stack up when dealing with high-frequency operations.

On the other hand, we use atomic operations to modify this 64-bit variable safely, without the need to lock and unlock a mutex.

Now, let’s break down how each method in WaitGroup works and understand how Go implements a lock-free algorithm using the state.

wg.Add(delta int)

#

When we pass a value to the wg.Add(?) method, it adjusts the counter accordingly.

If you provide a positive delta, it adds to the counter. Interestingly, you can also pass a negative delta, which will subtract from the counter.

As you might have guessed, wg.Done() is just a shortcut for wg.Add(-1):

// Done decrements the [WaitGroup] counter by one.

func (wg *WaitGroup) Done() {

wg.Add(-1)

}

However, if the negative delta causes the counter to drop below zero, the program will panic. The WaitGroup doesn’t check the counter before updating it, it updates first and then checks. This means that if the counter goes negative after calling wg.Add(?), it stays negative until the panic occurs.

So, if you catch this panic and plan to reuse the WaitGroup, be cautious.

Feel free to skip the code snippet below if you’re just looking for an overview, but it’s here if you want to dig deeper into how things work.

func (wg *WaitGroup) Add(delta int) {

... // we excludes the race stuffs

// Add the delta to the counter

state := wg.state.Add(uint64(delta) << 32)

// Extract the counter and waiter count from the state

v := int32(state >> 32)

w := uint32(state)

...

if v < 0 {

panic("sync: negative WaitGroup counter")

}

if w != 0 && delta > 0 && v == int32(delta) {

panic("sync: WaitGroup misuse: Add called concurrently with Wait")

}

if v > 0 || w == 0 {

return

}

if wg.state.Load() != state {

panic("sync: WaitGroup misuse: Add called concurrently with Wait")

}

// Reset waiters count to 0.

wg.state.Store(0)

for ; w != 0; w-- {

runtime_Semrelease(&wg.sema, false, 0)

}

}

Notice how you can increment the counter atomically by calling wg.state.Add(uint64(delta) << 32).

Here’s something that might not be widely known: when you add a positive delta to indicate the start of new tasks or goroutines, this must happen before calling wg.Wait().

So, if you’re reusing a WaitGroup, or if you want to wait for one batch of tasks, reset, and then wait for another batch, you need to make sure all calls to wg.Wait are completed before starting new wg.Add(positive) calls for the next round of tasks.

This avoids confusion about which tasks the WaitGroup is currently managing.

On the other hand, you can call wg.Add(?) with a negative delta at any time, as long as it doesn’t push the counter into negative territory.

Wait()

#

There isn’t a whole lot to say about wg.Wait(). It basically loops and tries to increase the waiter count using a CAS (Compare-And-Swap) atomic operation.

// Wait blocks until the [WaitGroup] counter is zero.

func (wg *WaitGroup) Wait() {

... // we excludes the race stuffs

for {

// Load the state of the WaitGroup

state := wg.state.Load()

v := int32(state >> 32)

w := uint32(state)

if v == 0 {

// Counter is 0, no need to wait.

...

return

}

// Increment waiters count.

if wg.state.CompareAndSwap(state, state+1) {

...

runtime_Semacquire(&wg.sema)

if wg.state.Load() != 0 {

panic("sync: WaitGroup is reused before previous Wait has returned")

}

...

return

}

}

}

If the CAS operation fails, it means that another goroutine has modified the state, maybe the counter reached zero or it was incremented/decremented. In that case, wg.Wait() can’t just assume everything is as it was, so it retries.

When the CAS succeeds, wg.Wait() increments the waiter count and then puts the goroutine to sleep using the semaphore.

If you recall, at the end of wg.Add(), it checks two conditions: if the counter is 0 and the waiter count is greater than 0. If both are true, it wakes up all the waiting goroutines and resets the state to 0.

And that’s pretty much the whole story with sync.WaitGroup. If you’ve made it this far, you’re clearly into the details, thanks for sticking with it!

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Inside Go’s Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus