- Blog /

- Go sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It

Go sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It

This post is part of a series about handling concurrency in Go:

- Go sync.Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- Go sync.WaitGroup and The Alignment Problem

- Go sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It (We’re here)

- Go sync.Cond, the Most Overlooked Sync Mechanism

- Go sync.Map: The Right Tool for the Right Job

- Go Sync.Once is Simple… Does It Really?

- Go Singleflight Melts in Your Code, Not in Your DB

In the VictoriaMetrics source code, we use sync.Pool a lot, and it’s honestly a great fit for how we handle temporary objects, especially byte buffers or slices.

It is commonly used in the standard library. For instance, in the encoding/json package:

package json

var encodeStatePool sync.Pool

// An encodeState encodes JSON into a bytes.Buffer.

type encodeState struct {

bytes.Buffer // accumulated output

ptrLevel uint

ptrSeen map[any]struct{}

}

In this case, sync.Pool is being used to reuse *encodeState objects, which handle the process of encoding JSON into a bytes.Buffer.

Instead of just throwing these objects after each use, which would only give the garbage collector more work, we stash them in a pool (sync.Pool). The next time we need something similar, we just grab it from the pool instead of making a new one from scratch.

You’ll also find multiple sync.Pool instances in the net/http package, that are used to optimize I/O operations:

package http

var (

bufioReaderPool sync.Pool

bufioWriter2kPool sync.Pool

bufioWriter4kPool sync.Pool

)

When the server reads request bodies or writes responses, it can quickly pull a pre-allocated reader or writer from these pools, skipping extra allocations. Furthermore, the 2 writer pools, *bufioWriter2kPool and *bufioWriter4kPool, are set up to handle different writing needs.

func bufioWriterPool(size int) *sync.Pool {

switch size {

case 2 << 10:

return &bufioWriter2kPool

case 4 << 10:

return &bufioWriter4kPool

}

return nil

}

Alright, that’s enough of the intro.

Today, we’re diving into what sync.Pool is all about, the definition, how it’s used, what’s going on under the hood, and everything else you might want to know.

By the way, if you want something more practical, there’s a good article from our Go experts showing how we use

sync.Poolin VictoriaMetrics: Performance optimization techniques in time series databases: sync.Pool for CPU-bound operations

What is sync.Pool?

#

To put it simply, sync.Pool in Go is a place where you can keep temporary objects for later reuse.

But here’s the thing, you don’t control how many objects stay in the pool, and anything you put in there can be removed at any time, without any warning and you’ll know why when reading last section.

The good point is, the pool is built to be thread-safe, so multiple goroutines can tap into it simultaneously. Not a big surprise, considering it’s part of the sync package.

“But why do we bother reusing objects?”

When you’ve got a lot of goroutines running at once, they often need similar objects. Imagine running go f() multiple times concurrently.

If each goroutine creates its own objects, memory usage can quickly increase and this puts a strain on the garbage collector because it has to clean up all those objects once they’re no longer needed.

This situation creates a cycle where high concurrency leads to high memory usage, which then slows down the garbage collector. sync.Pool is designed to help break this cycle.

type Object struct {

Data []byte

}

var pool sync.Pool = sync.Pool{

New: func() any {

return &Object{

Data: make([]byte, 0, 1024),

}

},

}

To create a pool, you can provide a New() function that returns a new object when the pool is empty. This function is optional, if you don’t provide it, the pool just returns nil if it’s empty.

In the snippet above, the goal is to reuse the Object struct instance, specifically the slice inside it.

Reusing the slice helps reduce unnecessary growth.

For instance, if the slice grows to 8192 bytes during use, you can reset its length to zero before putting it back in the pool. The underlying array still has a capacity of 8192, so the next time you need it, those 8192 bytes are ready to be reused.

func (o *Object) Reset() {

o.Data = o.Data[:0]

}

func main() {

testObject := pool.Get().(*Object)

// do something with testObject

testObject.Reset()

pool.Put(testObject)

}

The flow is pretty clear: you get an object from the pool, use it, reset it, and then put it back into the pool. Resetting the object can be done either before you put it back or right after you get it from the pool, but it’s not mandatory, it’s a common practice.

If you’re not a fan of using type assertions pool.Get().(*Object), there are a couple of ways to avoid it:

- Use a dedicated function to get the object from the pool:

func getObjectFromPool() *Object {

obj := pool.Get().(*Object)

return obj

}

- Create your own generic version of

sync.Pool:

type Pool[T any] struct {

sync.Pool

}

func (p *Pool[T]) Get() T {

return p.Pool.Get().(T)

}

func (p *Pool[T]) Put(x T) {

p.Pool.Put(x)

}

func NewPool[T any](newF func() T) *Pool[T] {

return &Pool[T]{

Pool: sync.Pool{

New: func() interface{} {

return newF()

},

},

}

}

The generic wrapper gives you a more type-safe way to work with the pool, avoiding type assertions.

Just note that, it adds a tiny bit of overhead due to the extra layer of indirection. In most cases, this overhead is minimal, but if you’re in a highly CPU-sensitive environment, it’s a good idea to run benchmarks to see if it’s worth it.

But wait, there’s more to it.

sync.Pool and Allocation Trap

#

If you’ve noticed from many previous examples, including those in the standard library, what we store in the pool is typically not the object itself but a pointer to the object.

Let me explain why with an example:

var pool = sync.Pool{

New: func() any {

return []byte{}

},

}

func main() {

bytes := pool.Get().([]byte)

// do something with bytes

_ = bytes

pool.Put(bytes)

}

We’re using a pool of []byte. Generally (though not always), when you pass a value to an interface, it may cause the value to be placed on the heap. This happens here too, not just with slices but with anything you pass to pool.Put() that isn’t a pointer.

If you check using escape analysis:

// escape analysis

$ go build -gcflags=-m

bytes escapes to heap

Now, I don’t say our variable bytes moves to the heap, I would say “the value of bytes escapes to the heap through the interface”.

To really get why this happens, we’d need to dig into how escape analysis works (which we might do in another article). However, if we pass a pointer to pool.Put(), there is no extra allocation:

var pool = sync.Pool{

New: func() any {

return new([]byte)

},

}

func main() {

bytes := pool.Get().(*[]byte)

// do something with bytes

_ = bytes

pool.Put(bytes)

}

Run the escape analysis again, you’ll see it’s no longer escapes to the heap. If you want to know more, there is an example in Go source code.

sync.Pool Internals

#

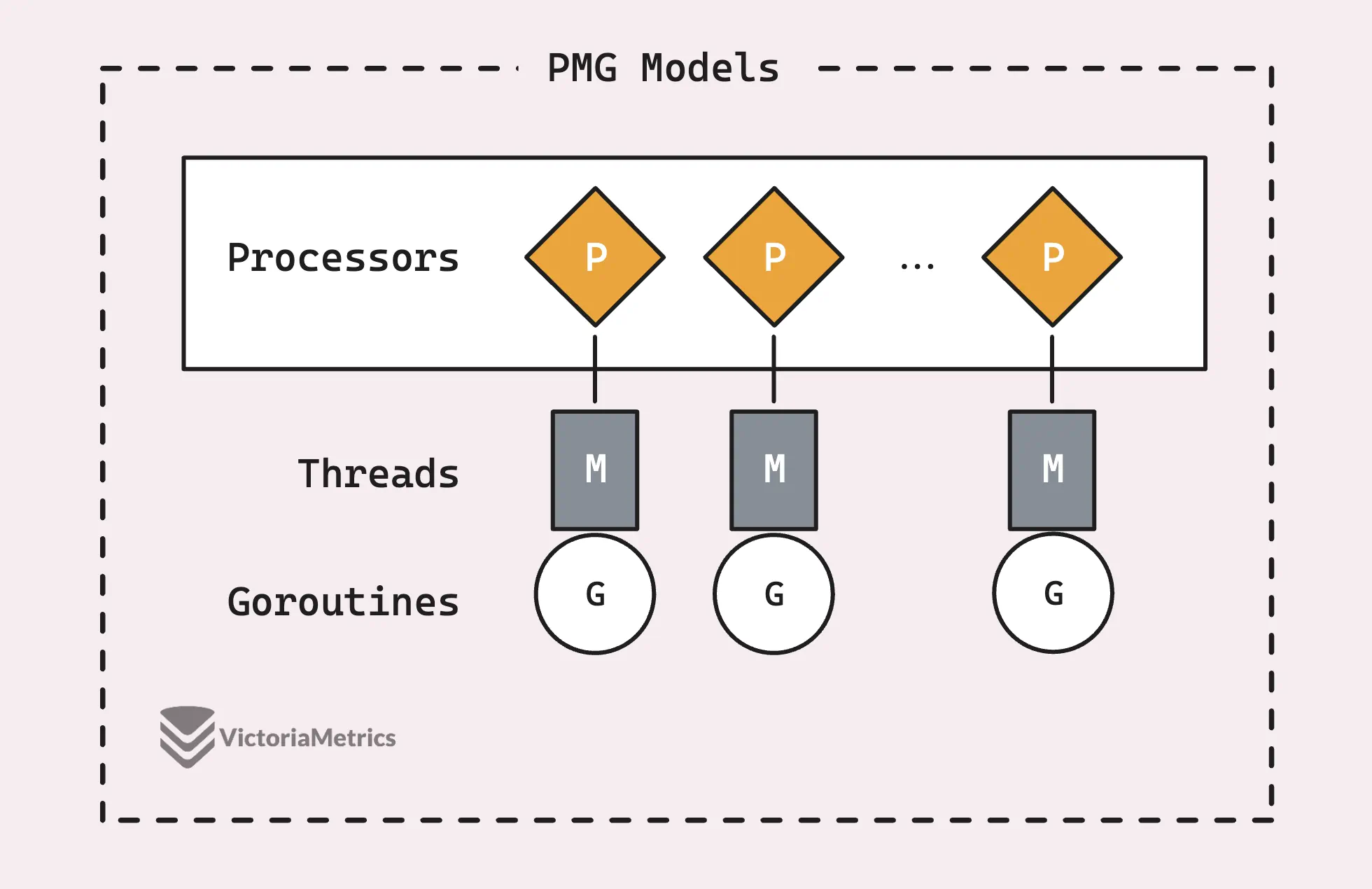

Before we get into how sync.Pool actually works, it’s worth getting a grip on the basics of Go’s PMG scheduling model, this is really the backbone of why sync.Pool is so efficient.

There’s a good article that breaks down the PMG model with some visuals: PMG models in Go

If you’re feeling lazy today and looking for a simplified summary, I’ve got your back:

PMG stands for P (logical processors), M (machine threads), and G (goroutines). The key point is that each logical processor (P) can only have one machine thread (M) running on it at any time. And for a goroutine (G) to run, it needs to be attached to a thread (M).

This boils down to 2 key points:

- If you’ve got n logical processors (P), you can run up to n goroutines in parallel, as long as you’ve got at least n machine threads (M) available.

- At any one time, only one goroutine (G) can run on a single processor (P). So, when a P1 is busy with a G, no other G can run on that P1 until the current G either gets blocked, finishes up, or something else happens to free it up.

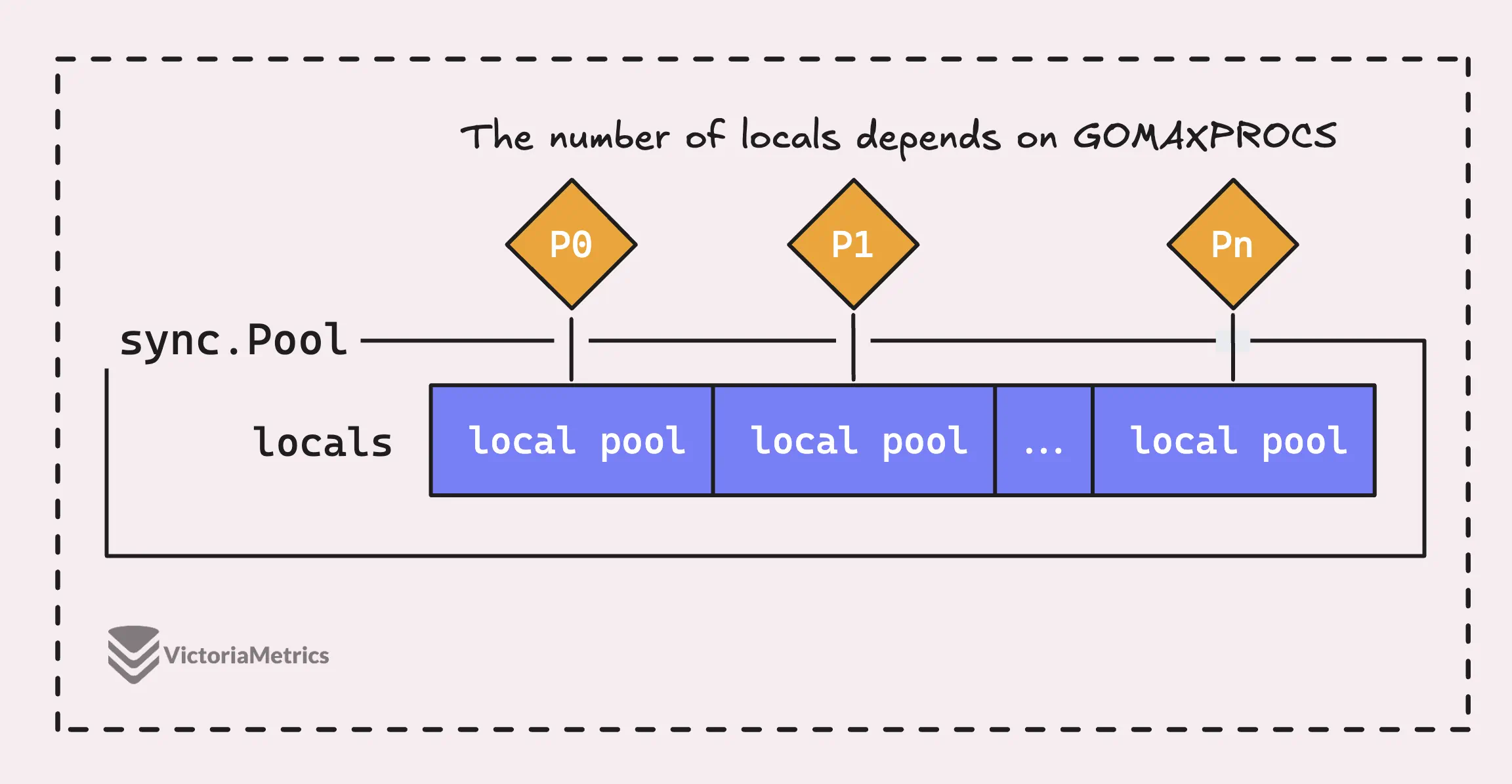

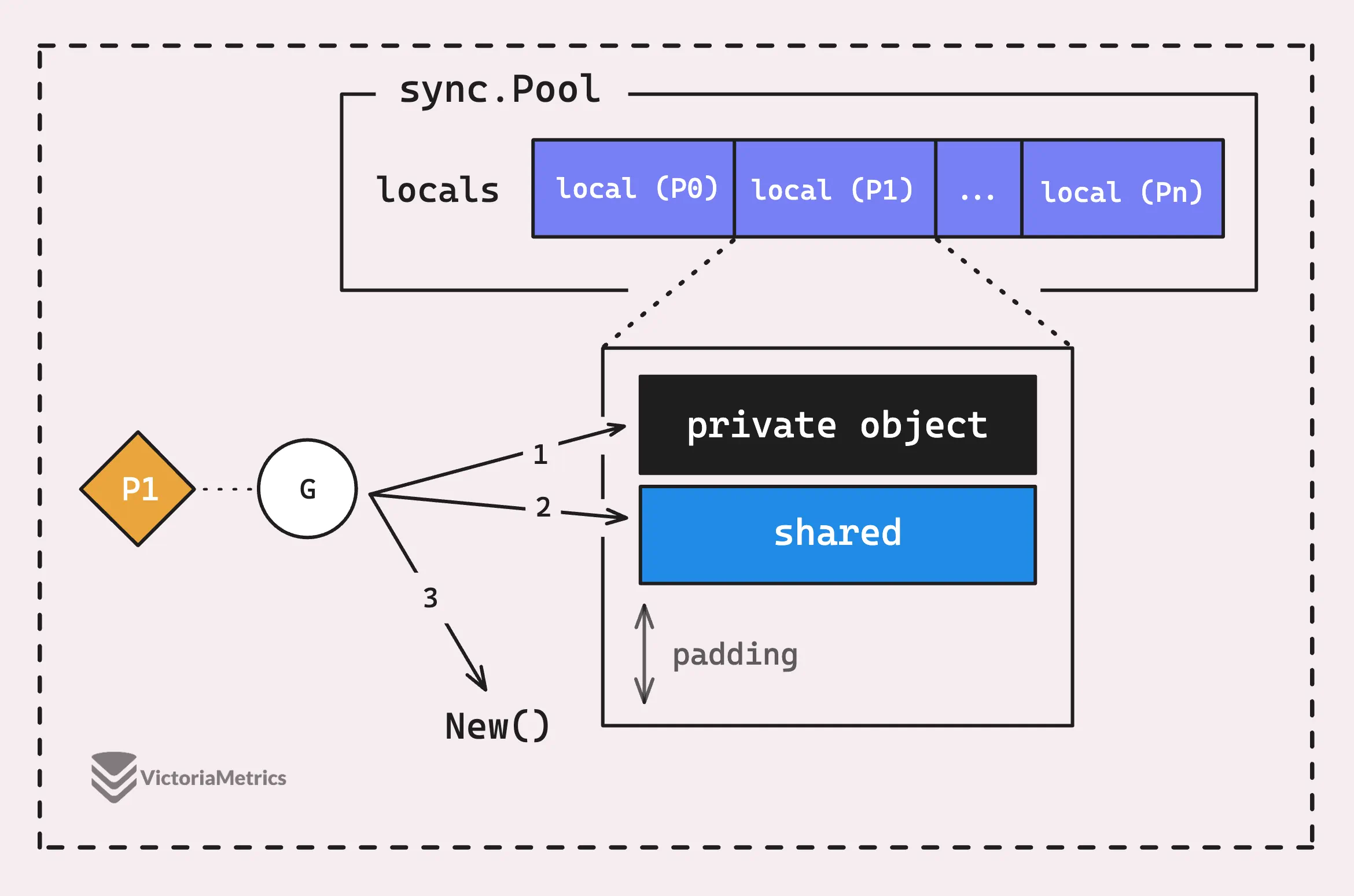

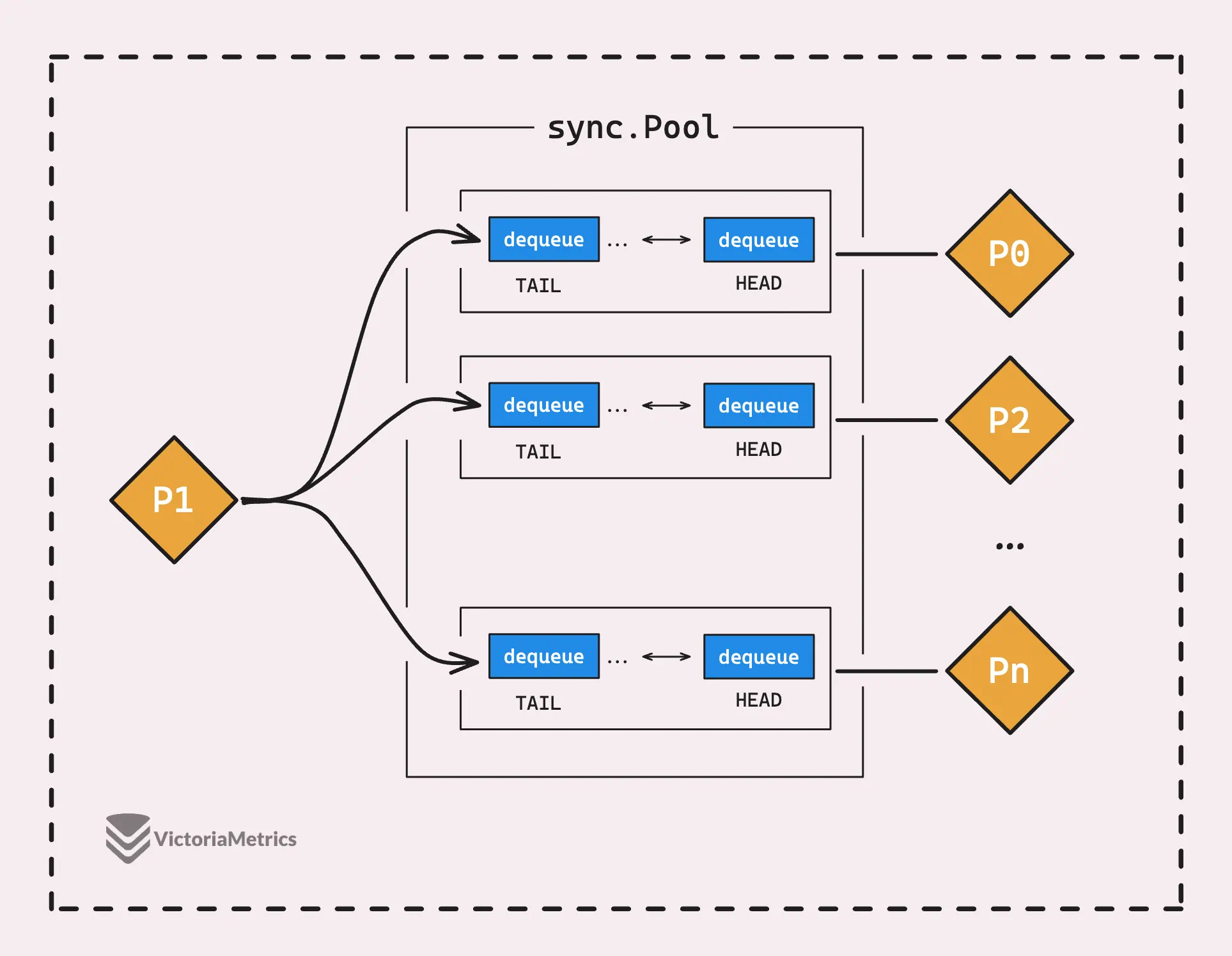

But the thing is, a sync.Pool in Go isn’t just one big pool, it’s actually made up of several ’local’ pools, with each one tied to a specific processor context, or P, that Go’s runtime is managing at any given time.

When a goroutine running on a processor (P) needs an object from the pool, it’ll first check its own P-local pool before looking anywhere else.

This is a smart design choice because it means that each logical processor (P) has its own set of objects to work with. This reduces contention between goroutines since only one goroutine can access its P-local pool at a time.

So, the process is super fast because there’s no chance of two goroutines trying to grab the same object from the same local pool at the same time.

Pool Local & False Sharing Problem

#

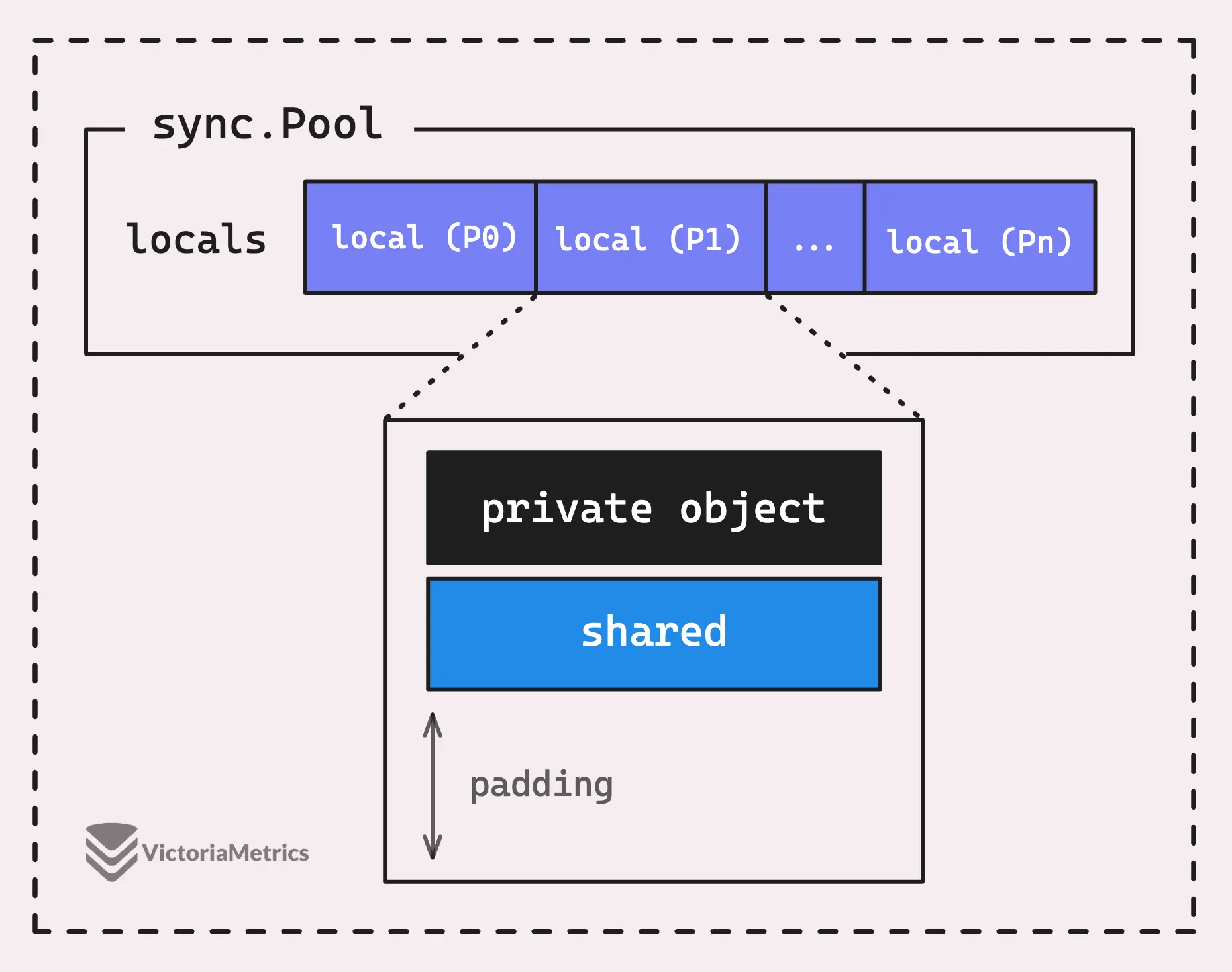

Earlier, we mentioned that ‘Only one goroutine can access the P-local pool at the same time’, but the reality is a bit more nuanced.

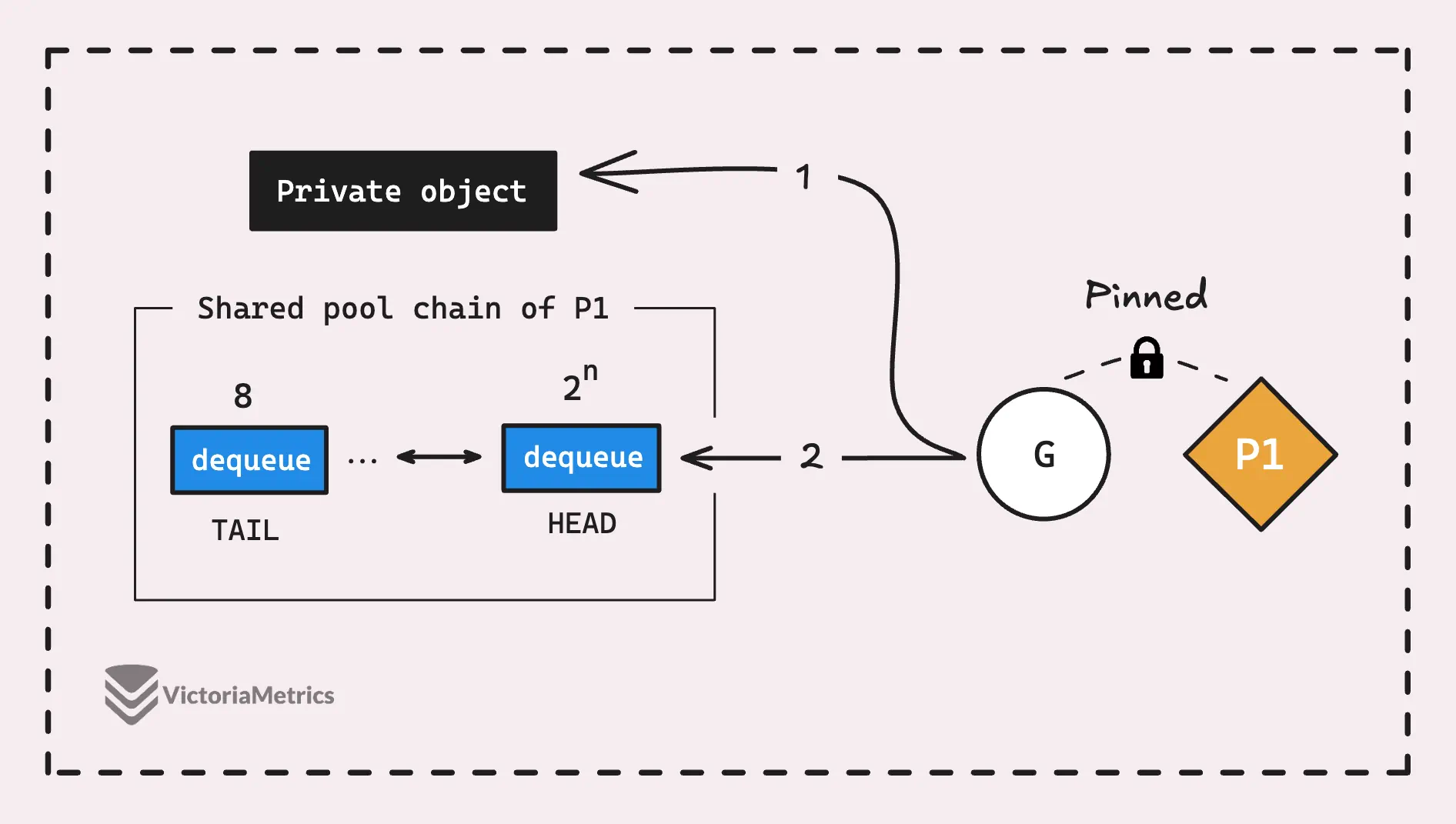

Take a look at the below diagram, each P-local pool actually has two main parts: the shared pool chain (shared) and a private object (private).

Here is the definition of local pool in Go source code:

type poolLocalInternal struct {

private any

shared poolChain

}

type poolLocal struct {

poolLocalInternal

pad [128 - unsafe.Sizeof(poolLocalInternal{})%128]byte

}

The private field is where a single object is stored, and only the P that owns this P-local pool can access it, let’s call it the private object.

It’s designed so a goroutine can quickly grab a reusable object (which is private object) without needing to mess with any mutex or synchronization tricks. In other words, only one goroutine can access its own private object, no other goroutine can compete with it.

But if the private object isn’t available, that’s when the shared pool chain (shared) steps in.

“Why wouldn’t it be available? I thought only one goroutine could get and put the private object back into the pool. So, who’s the competition?”

Good question.

While it’s true that only one goroutine can access the private object of a P at a time, there’s a catch. If Goroutine A grabs the private object and then gets blocked or preempted, Goroutine B might start running on that same P. When that happens, Goroutine B won’t be able to access the private object because Goroutine A still has it.

Now, unlike the simple of private object, the shared pool chain (shared) is a bit more complex.

So the Get() flow could be simply imagined like this:

The above diagram isn’t entirely accurate since it doesn’t account for the victim pool.

If the shared pool chain is empty as well, sync.Pool will either create a new object (assuming you’ve provided a New() function) or just return nil. And, by the way, there’s also a victim mechanism inside the shared pool, but we’ll also cover that in the last.

“Wait, I see the

padfield in the P-local pool. What’s that all about?”

One thing that jumps out when you look at the P-local pool structure is this pad attribute. It’s something that VictoriaMetrics’ CTO, Aliaksandr Valialkin, adjusted in this commit:

type poolLocal struct {

poolLocalInternal

pad [128 - unsafe.Sizeof(poolLocalInternal{})%128]byte

}

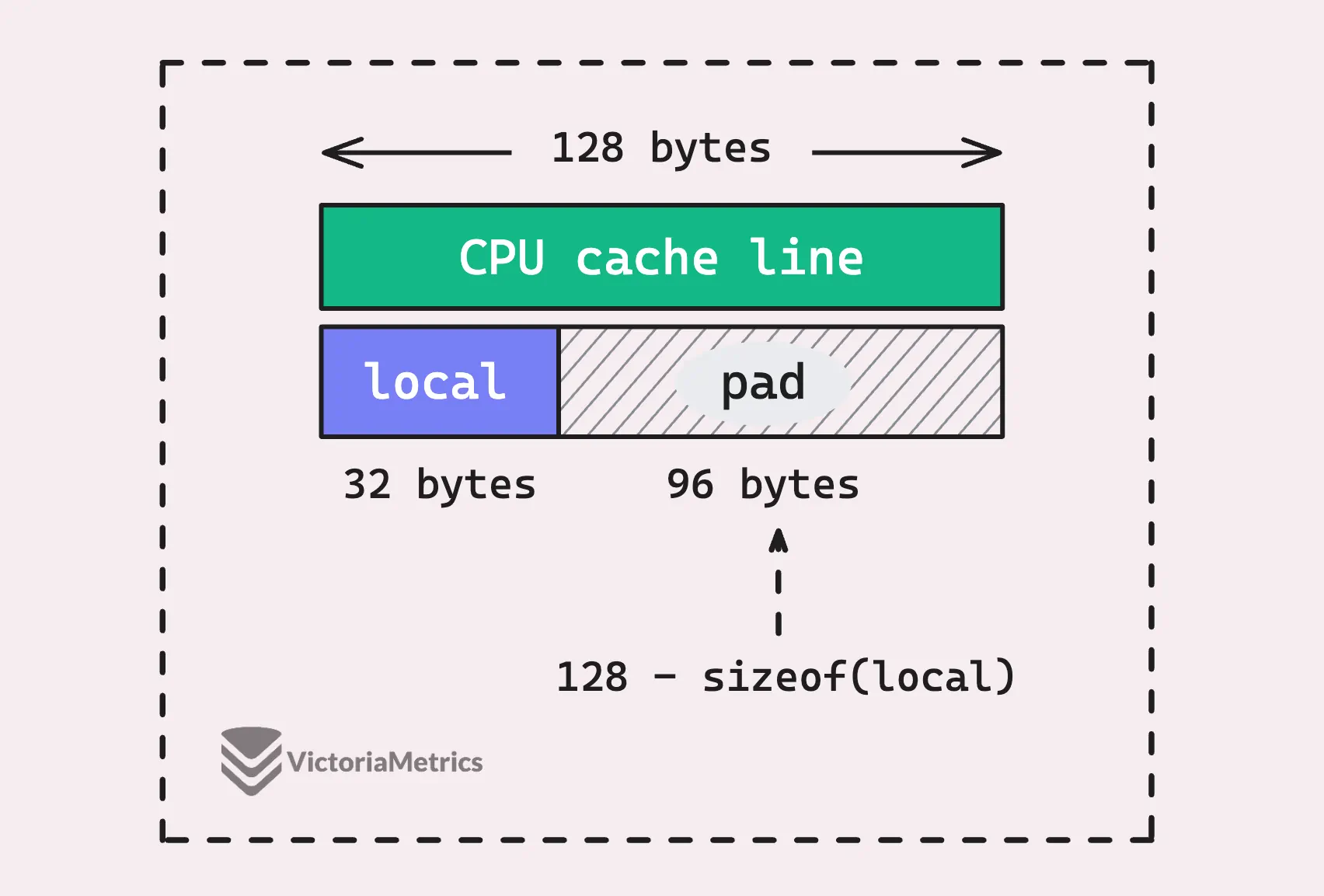

This pad might seem a bit odd since it doesn’t add any direct functionality, but it’s actually there to prevent a problem that can crop up on modern multi-core processors called false sharing.

To get why this matters, we need to dig into how CPUs handle memory and caching. So, brace yourself for a bit of a deep dive into the inner workings of CPUs (but don’t worry, we’ll keep it manageable).

Modern CPUs use a component called the CPU cache to speed up memory access, this cache is divided into units called cache lines, which typically hold either 64 or 128 bytes of data. When the CPU needs to access memory, it doesn’t just grab a single byte or word—it loads an entire cache line.

This means that if two pieces of data are close together in memory, they might end up on the same cache line, even if they’re logically separate.

Now, in the context of Go’s sync.Pool, each logical processor (P) has its own poolLocal, which is stored in an array. If the poolLocal structure is smaller than the size of a cache line, multiple poolLocal instances from different Ps can end up on the same cache line. This is where things can go sideways. If two Ps, running on different CPU cores, try to access their own poolLocal at the same time, they could unintentionally step on each other’s toes.

Even though each P is only dealing with its own poolLocal, these structures might share the same cache line.

When one processor modifies something in a cache line, the entire cache line is invalidated in other processors’ caches, even if they’re working with different variables within that same line. This can cause a serious performance hit because of unnecessary cache invalidations and extra memory traffic.

That’s where the 128 - unsafe.Sizeof(poolLocalInternal{})%128 comes in.

It calculates the number of bytes needed to pad the P-local pool so that its total size is a multiple of 128 bytes. This padding helps each poolLocal gets its own cache line, preventing false sharing and keeping things running faster, free-conflict.

Pool Chain & Pool Dequeue

#

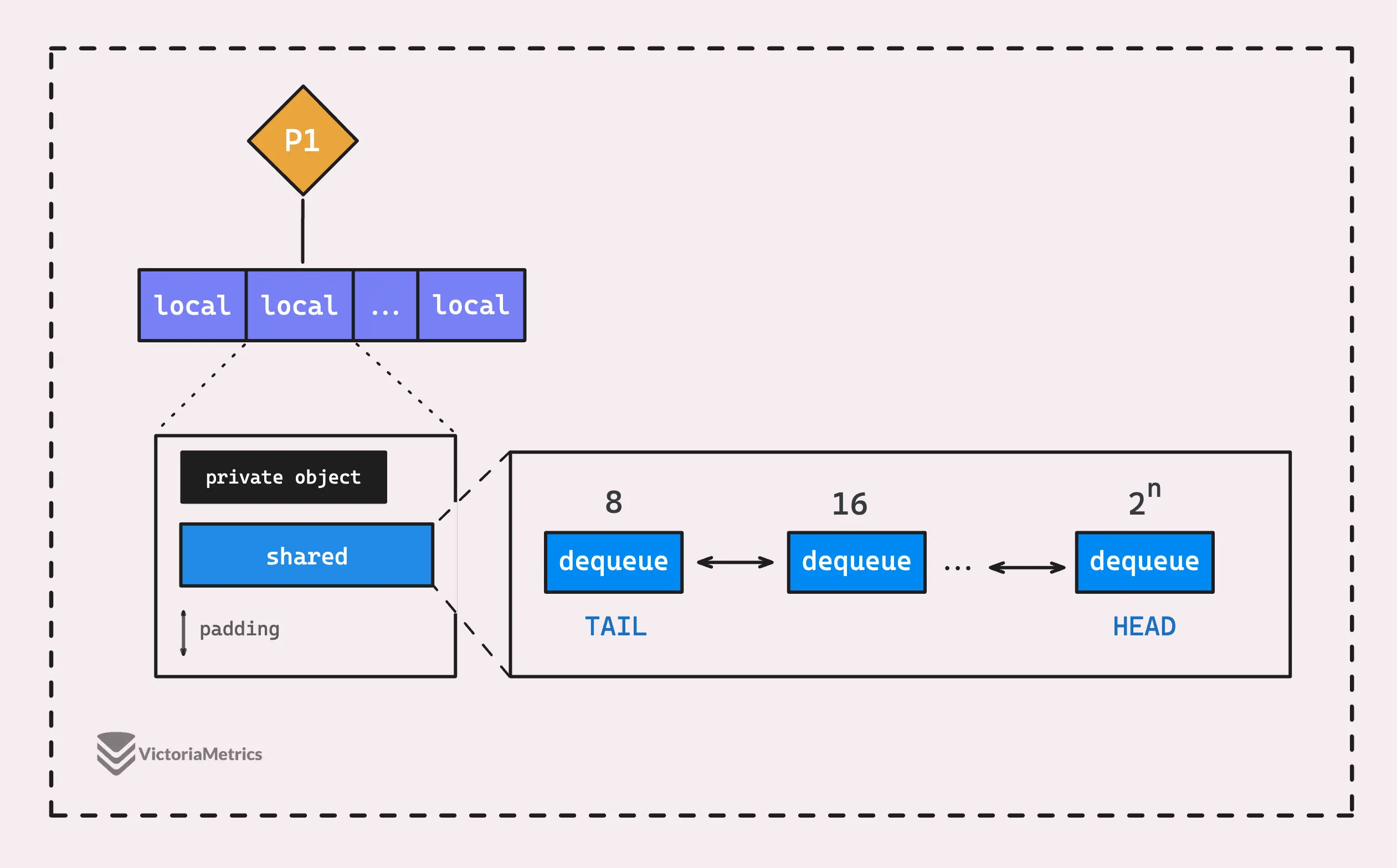

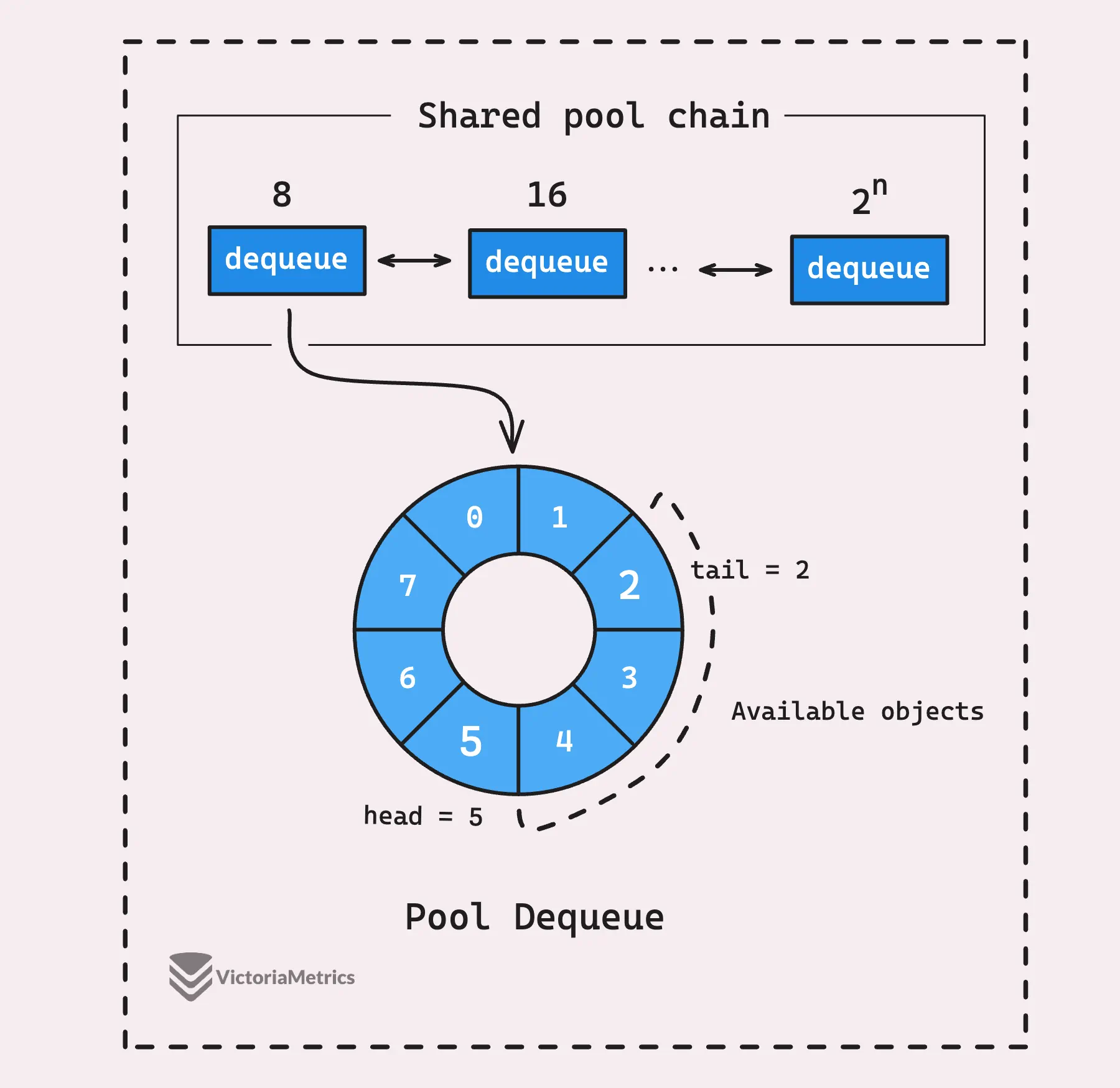

The shared pool chain in sync.Pool is represented by a type called poolChain.

From the name, you might guess it’s a double-linked list, and you’d be right. But here’s the twist: each node in this list isn’t just a reusable object. Instead, it’s another structure called a pool dequeue (poolDequeue).

type poolChain struct {

head *poolChainElt

tail atomic.Pointer[poolChainElt]

}

type poolChainElt struct {

poolDequeue

next, prev atomic.Pointer[poolChainElt]

}

The design of the poolChain is pretty strategic, this diagram below shows us something:

When the current pool dequeue (the one at the head of the list) gets full, a new pool dequeue is created that’s double the size of the previous one. This new, larger pool is then added to the chain.

If you take a look at the poolChain struct, you’ll notice it has two fields: a pointer head *poolChainElt and an atomic pointer tail atomic.Pointer[poolChainElt].

These fields reveal how the mechanism works:

- The producer (the P that owns the current P-local pool) only adds new items to the most recent pool dequeue, which we call the head. Since only the producer is touching the head, there’s no need for locks or any fancy synchronization tricks, so it’s really fast.

- Consumers (other Ps) take items from the pool dequeue at the tail of the list. Since multiple consumers might try to pop items at the same time, access to the tail is synchronized using atomic operations to keep things in order.

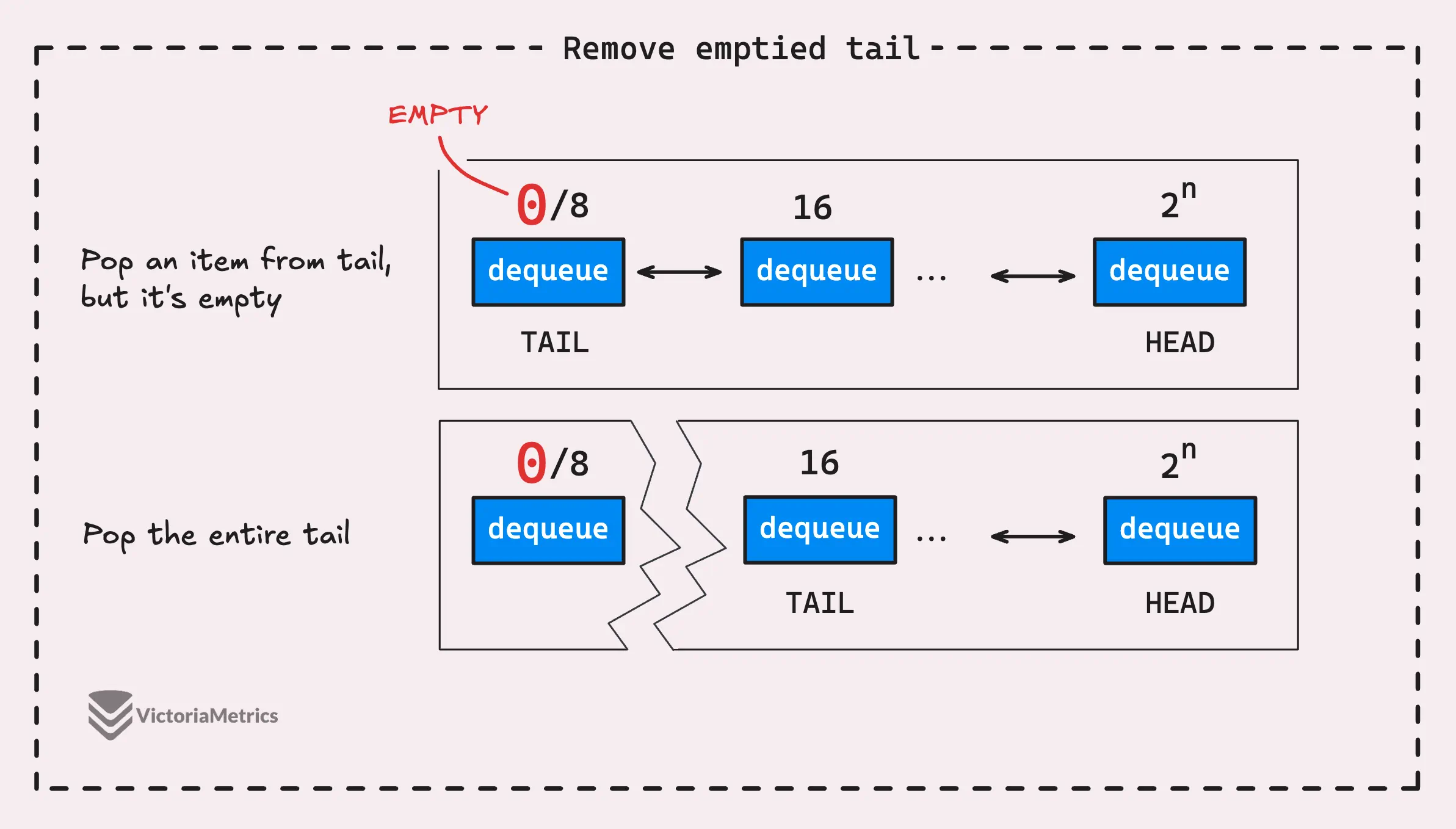

But here’s the key part:

- When the pool dequeue at the tail is completely emptied, it gets removed from the list, and the next pool dequeue in line becomes the new tail. But the situation at the head is a bit different.

- When the pool dequeue at the head runs out of items, it doesn’t get removed. Instead, it stays in place, ready to be refilled when new items are added.

Now, let’s take a look at how the pool dequeue is defined. As the name “dequeue” suggests, it’s a double-ended queue.

Unlike a regular queue where you can only add elements at the back and remove them from the front, a dequeue lets you insert and delete elements at both the front and the back.

Its mechanism is actually quite similar to the pool chain. It’s designed so that one producer can add or remove items from the head, while multiple consumers can take items from the tail.

type poolDequeue struct {

headTail atomic.Uint64

vals []eface

}

The producer (which is the current P) can add new items to the front of the queue or take items from it.

Meanwhile, the consumers only take items from the tail of the queue. This queue is lock-free, which means it doesn’t use locks to manage the coordination between the producer and consumers, only using atomic operations.

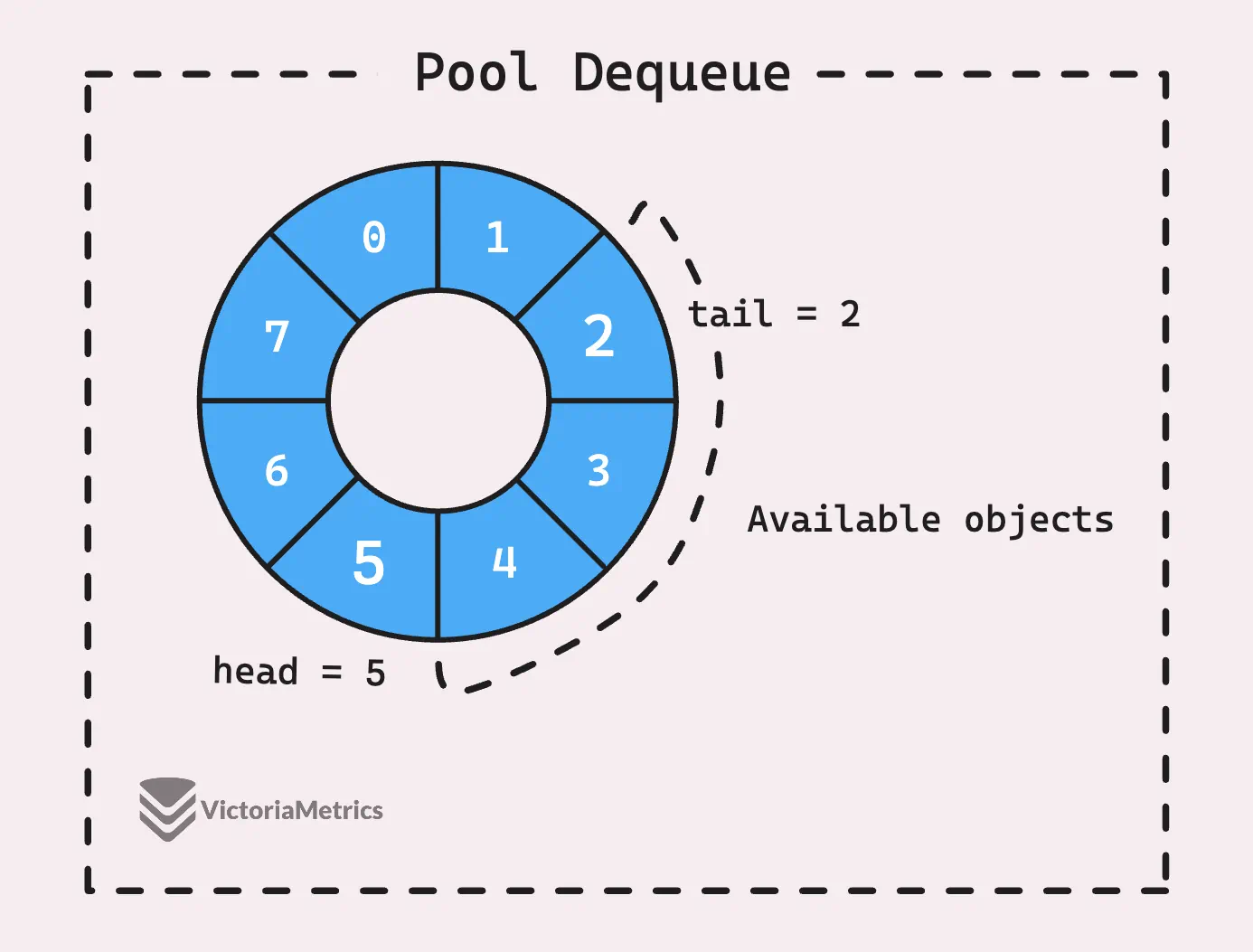

You can think of this queue as a kind of ring buffer.

“What’s a ring buffer?”

A ring buffer, or circular buffer, is a data structure that uses a fixed-size array to store elements in a loop-like fashion. It’s called a “ring” because, in a way, the end of the buffer wraps around to meet the beginning, making it look like a circle.

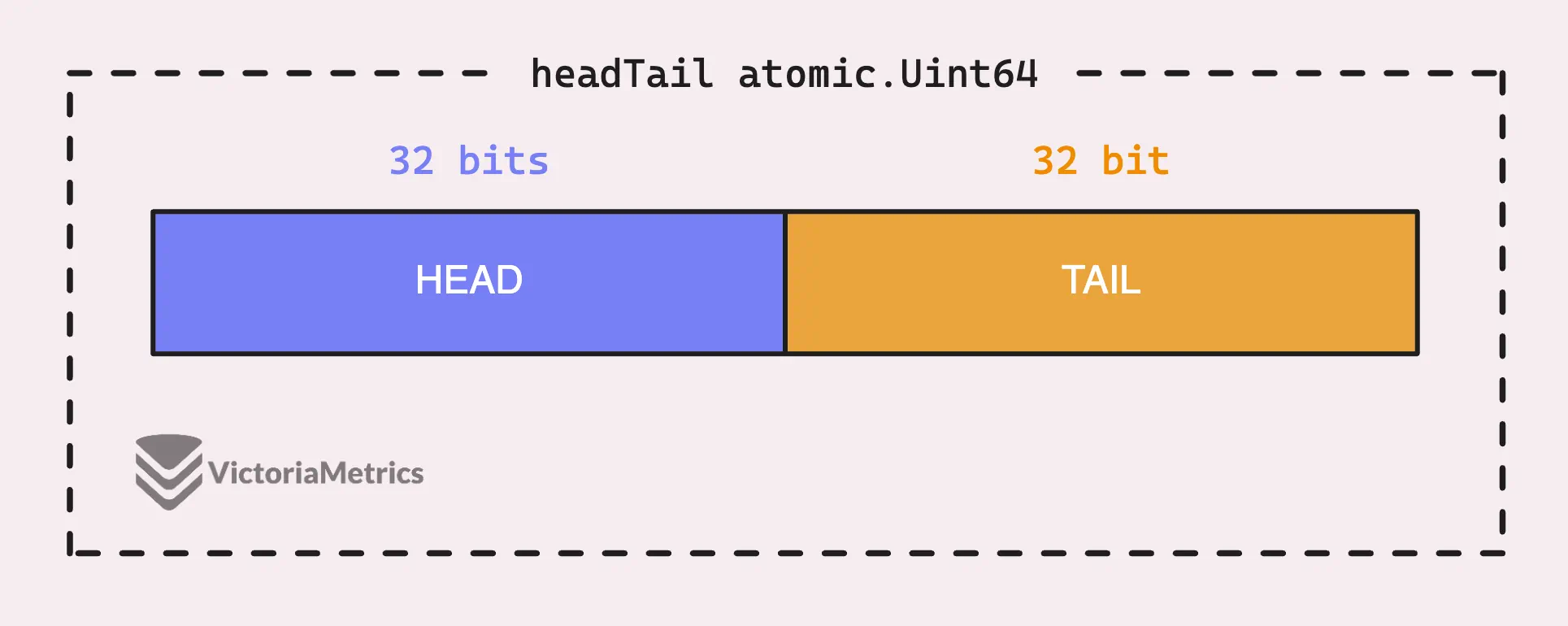

In the context of the pool dequeue we’re talking about, the headTail field is a 64-bit integer that packs two 32-bit indexes into a single value.

These indexes are the head and tail of the queue and help keep track of where data is being stored and accessed in the buffer

- The tail index points to where the oldest item in the buffer is and when consumers (like other goroutines) read from the buffer, they start here and move forward.

- The head index is where the next piece of data will be written. As new data comes in, it’s placed at this head index, and then the index moves to the next available slot.

“But why? why not make 2 fields head and tail?”

By packing the head and tail indices into a single 64-bit value, the code can update both indices in one go, making the operation atomic.

This is especially useful when two consumers (or a consumer and a producer) try to pop an item from the queue at the same time. The CompareAndSwap (CAS) operation, d.headTail.CompareAndSwap(ptrs, ptrs2), ensures that only one of them succeeds. The other one fails and retries, keeping things orderly without any complex locking.

The actual data in the queue is stored in a circular buffer called vals, which has to be a power of two in size.

This design choice makes it easier to handle the queue wrapping around when it reaches the end of the buffer. Each slot in this buffer is an eface value, which is how Go represents an empty interface (interface{}) under the hood.

type eface struct {

typ, val unsafe.Pointer

}

A slot in the buffer stays “in use” until two things happen:

- The tail index moves past the slot, meaning the data in that slot has been consumed by one of the consumers.

- The consumer who accessed that slot sets it to nil, signaling that the producer can now use that slot to store new data.

In short, the pool chain combines a linked list and a ring buffer for each node. When one dequeue fills up, a new, larger one is created and linked to the head of the chain. This setup helps manage a high volume of objects efficiently.

Now, it’s time to dive into the flow: how objects are taken out, put back in, and automatically deallocated. This will clarify Go’s statement about sync.Pool: “Any item stored in the Pool may be removed automatically at any time without notification.”

Pool.Put()

#

Let’s start with the Put() flow because it’s a bit more straightforward than Get(), plus it ties into another process: pinning a goroutine to a P.

When a goroutine calls Put() on a sync.Pool, the first thing it tries to do is store the object in the private spot of the P-local pool for the current P. If that private spot is already occupied, the object gets pushed to the head of the pool chain, which is the shared part.

func (p *Pool) Put(x interface{}) {

// If the object is nil, it will do nothing

if x == nil {

return

}

// Pin the current P's P-local pool

l, _ := p.pin()

// If the private pool is not there, create it and set the object to it

if l.private == nil {

l.private = x

x = nil

}

// If the private object is there, push it to the head of the shared chain

if x != nil {

l.shared.pushHead(x)

}

// Unpin the current P

runtime_procUnpin()

}

We haven’t talked about the pin() or runtime_procUnpin() functions yet, but they’re important for both Get() and Put() operations because they ensure the goroutine stays “pinned” to the current P. Here is what I mean:

Starting with Go 1.14, Go introduced preemptive scheduling, which means the runtime can pause a goroutine if it’s been running on a processor P for too long, usually around 10ms, to give other goroutines a chance to run.

This is generally good for keeping things fair and responsive, but it can cause issues when dealing with sync.Pool.

Operations like Put() and Get() in sync.Pool assume that the goroutine stays on the same processor (say, P1) throughout the entire operation. If the goroutine is preempted in the middle of these operations and then resumed on a different processor (P2), the local data it was working with could end up being from the wrong processor.

So, what does the pin() function do? Here’s a comment from the Go source code that explains it:

// pin pins the current goroutine to P, disables preemption and

// returns poolLocal pool for the P and the P's id.

// Caller must call runtime_procUnpin() when done with the pool.

func (p *Pool) pin() (*poolLocal, int) { ... }

Basically, pin() temporarily disables the scheduler’s ability to preempt the goroutine while it’s putting an object into the pool.

Even though it says “pins the current goroutine to P,” what’s actually happening is that the current thread (M) is locked to the processor (P), which prevents it from being preempted. As a result, the goroutine running on that thread will also not be preempted.

As a side effect, pin() also updates the number of processors (Ps) if you happen to change GOMAXPROCS(n) (which controls the number of Ps) at runtime. However, that’s not the main focus here.

How about the shared pool chain?

When you need to add an item to the chain, the operation first checks the head of the chain. Remember the head *poolChainElt pointer? That’s the most recent pool dequeue in the list.

Depending on the situation, here’s what can happen:

- If the head buffer of the chain is

nil, meaning there’s no pool dequeue in the chain yet, a new pool dequeue is created with an initial buffer size of 8. The item is then placed into this brand-new pool dequeue. - If the head buffer of the chain isn’t

niland that buffer isn’t full, the item is simply added to the buffer at the head position. - If the head buffer of the chain isn’t

nil, but that buffer is full, meaning the head index has wrapped around and caught up with the tail index, then a new pool dequeue is created. This new pool has a buffer size that’s double the size of the current head. The item is placed into this new pool dequeue, and the head of the pool chain is updated to point to this new pool.

And that’s pretty much it for the Put() flow. It’s a relatively simple process because it doesn’t involve interacting with the local pool other processors (Ps); everything happens within the current head of the pool chain.

Now, let’s get into the more complex part sync.Pool.Get()

sync.Pool.Get()

#

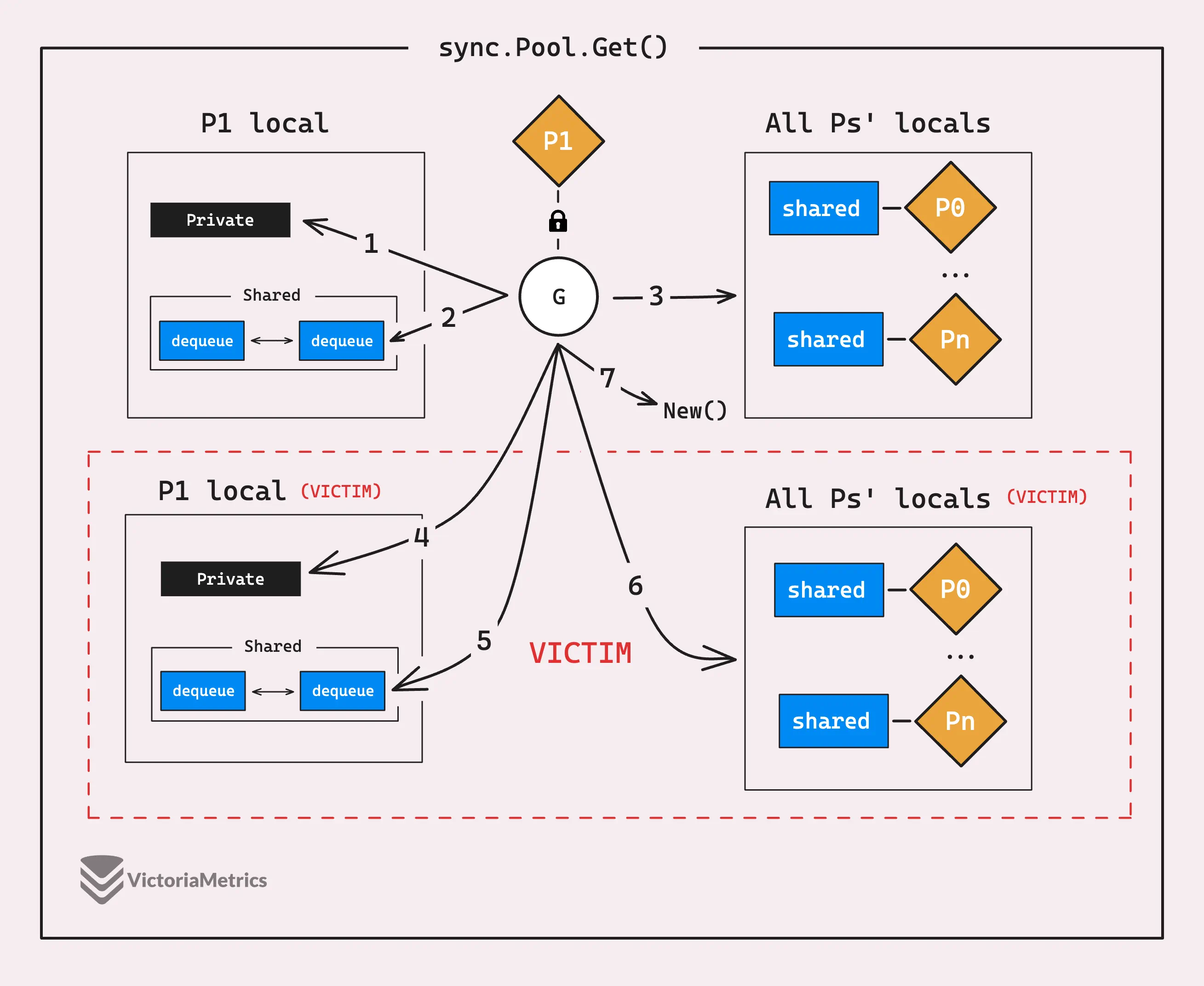

At first glance, the Get() function seems pretty similar to Put().

It starts by pinning the current goroutine to its P to prevent preemption, then checks and grabs the private object from its P-local pool without needing any synchronization. If the private object isn’t there, it checks the shared pool chain and pops the head of the chain.

Only the goroutine running on the current P-local pool can access the head of the chain, which is why we use popHead():

func (p *Pool) Get() interface{} {

// Pin the current P's P-local pool

l, pid := p.pin()

// Get the private object from the current P-local pool

x := l.private

l.private = nil

// If the private object is not there, pop the head of the shared pool chain

if x == nil {

x, _ = l.shared.popHead()

// Steal from other P's cache

if x == nil {

x = p.getSlow(pid)

}

}

runtime_procUnpin()

// If the object is still not there, create a new object from the factory function

if x == nil && p.New != nil {

x = p.New()

}

return x

}

Unlike in p.pin() for Put(), here we also get the pid, which is the ID of the P that the current goroutine is running on. We need this for the stealing process, which comes into play if the fast path fails.

The fast path is when the object is available in the current P’s cache. But if that doesn’t work out, meaning the private object and the head of the shared chain are both empty, the slow path (getSlow) takes over.

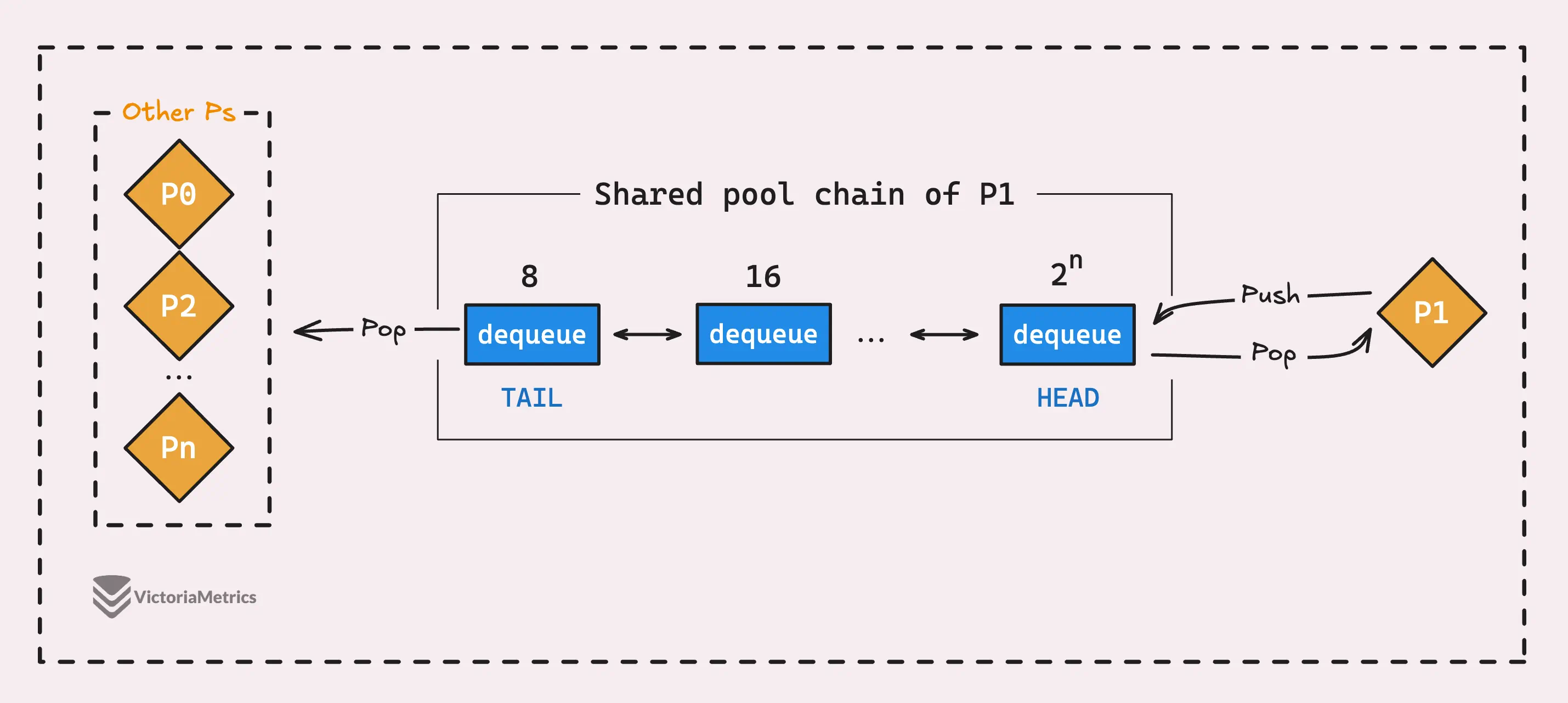

In the slow path, we try to steal objects from the cache pools of other processors (Ps).

The idea behind stealing is to reuse objects that might be sitting idle in the caches of other processors, instead of creating new objects from scratch. If another P has extra objects in its cache pool, the current P can grab those objects and put them to use.

The stealing process basically loops through all the Ps, except the current one (pid), and tries to grab an object from each P’s shared pool chain:

for i := 0; i <int(size); i++ {

l := indexLocal(locals, (pid+i+1)%int(size))

if x, _ := l.shared.popTail(); x != nil {

return x

}

}

As we’ve talked about before, in a poolChain, the provider (the current P) pushes and pops at the head, while multiple consumers (other Ps) pop from the tail.

So, popTail looks at the last pool dequeue in the linked list and tries to grab data from the end of that pool dequeue.

- If it finds data, the steal is successful, and the data is returned.

- If it doesn’t find any data in that pool dequeue, the tail index increases, and that pool dequeue gets removed from the chain.

This process continues until it either successfully steals some data or runs out of options in all the pool chains.

“So if the stealing process fails, does it create a new object using

New()?”

Not quite.

If, after all the stealing attempts, it still can’t find any data, the function then tries to get data from what’s called the “victim.” This is a new concept related to how sync.Pool cleans up objects, and we’ll get into the details of the victim mechanism in the next section.

Let brief what we’ve talked about so far.

We’re trying to grab an object in every possible way, and if nothing is found, it finally creates a new object using New(). But if New() is nil, then it just returns nil. Simple as that.

Now, after the attempt with the victim pool, it is atomically marked as empty (though concurrent accesses may still retrieve from it). Subsequent Get() operations will skip checking the victim cache until it’s filled up again.

So, what is the victim pool?

Victim Pool

#

Even though sync.Pool is built for better manage resources, it doesn’t give us, developers, direct tools to clean up or manage object lifecycles. Instead, sync.Pool handles cleanup behind the scenes to avoid unchecked growth, which could lead to memory leaks.

The primary way this cleanup happens is through Go’s garbage collector (GC).

Remember when we talked about pin()? It turns out pin() has another side effect. Every time a sync.Pool calls pin() for the first time (or after the number of Ps has changed via GOMAXPROCS), it gets added to a global slice called allPools in the sync package:

package sync

var (

allPoolsMu Mutex

// allPools is the set of pools that have non-empty primary

// caches. Protected by either 1) allPoolsMu and pinning or 2)

// STW.

allPools []*Pool

// oldPools is the set of pools that may have non-empty victim

// caches. Protected by STW.

oldPools []*Pool

)

This allPools []*Pool slice keeps track of all the active sync.Pool instances in your application.

Before each garbage collection (GC) cycle starts, Go’s runtime triggers a cleanup process that clears out the allPools slice. Here’s how it works:

- Before the GC kicks in, it calls

clearPool, which transfers all the objects in thesync.Pool, including the private objects and shared pool chains, over to what’s called the victim area. - These objects aren’t immediately thrown away, they’re held in this victim area for now.

- Meanwhile, the objects that were already in the victim area from the last GC cycle get fully cleared out during the current GC cycle.

Or you may interested to look at the source code:

func poolCleanup() {

// Drop victim caches from all pools.

for _, p := range oldPools {

p.victim = nil

p.victimSize = 0

}

// Move primary cache to victim cache.

for _, p := range allPools {

p.victim = p.local

p.victimSize = p.localSize

p.local = nil

p.localSize = 0

}

// The pools with non-empty primary caches now have non-empty

// victim caches and no pools have primary caches.

oldPools, allPools = allPools, nil

}

But why do we need this victim mechanism? Why does it take up to two GC cycles to clear all the objects in the pool?

The reason for using the victim mechanism in sync.Pool is to avoid suddenly and completely emptying the pool right after a GC cycle. If the pool were emptied all at once, it could lead to performance issues, as any new requests for objects would require them to be recreated from scratch. So we move objects to the victim area first, sync.Pool ensures there’s a buffer period where objects can still be reused before they’re fully discarded.

To sum up, an object in sync.Pool takes at least 2 GC cycles to be fully removed.

This could be a problem for programs with a low GOGC value, which controls how frequently the GC runs to clean up unused objects. If GOGC is set too low, the cleanup process might remove unused objects too quickly, leading to more cache misses.

Final words: Even with

sync.Pool, if you’re dealing with extremely high concurrency and slow GC, you might experience more overhead. In this case, a good solution could be to implement rate limiting onsync.Poolusage.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Inside Go’s Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus