- Blog /

- Go sync.Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

Go sync.Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

This post is part of a series about handling concurrency in Go:

- Go sync.Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode (We’re here)

- Go sync.WaitGroup and The Alignment Problem

- Go sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It

- Go sync.Cond, the Most Overlooked Sync Mechanism

- Go sync.Map: The Right Tool for the Right Job

- Go Sync.Once is Simple… Does It Really?

- Go Singleflight Melts in Your Code, Not in Your DB

Mutex, or MUTual EXclusion, in Go is basically a way to make sure that only one goroutine is messing with a shared resource at a time. This resource can be a piece of code, an integer, a map, a struct, a channel, or pretty much anything.

Now, the explanation above isn’t strictly the ‘academic’ definition, but it’s a useful way to understand the concept.

In today’s discussion, we’re still going from the problem, moving on to the solution, and then diving into how it’s actually put together under the hood.

Why we need sync.Mutex?

#

If you’ve spent enough time messing around with maps in Go, you might run into a nasty error like this:

fatal error: concurrent map read and map write

This happens because we’re not protecting our map from multiple goroutines trying to access and write to it at the same time.

Now, we could use a map with a mutex or a sync.Map, but that’s not our focus today. The star of the show here is sync.Mutex, and it’s got three main operations: Lock, Unlock, and TryLock (which we won’t get into right now).

When a goroutine locks a mutex, it’s basically saying, ‘Hey, I’m going to use this shared resource for a bit,’ and every other goroutine has to wait until the mutex is unlocked. Once it’s done, it should unlock the mutex so other goroutines can get their turn.

Simple as that, Let’s see how it works with a simple counter example:

var counter = 0

var wg sync.WaitGroup

func incrementCounter() {

counter++

wg.Done()

}

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go incrementCounter()

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println(counter)

}

So, we’ve got this counter variable that’s shared between 1000 goroutines. A newcomer to Go would think the result should be 1000, but it never is. This is because of something called a “race condition.”

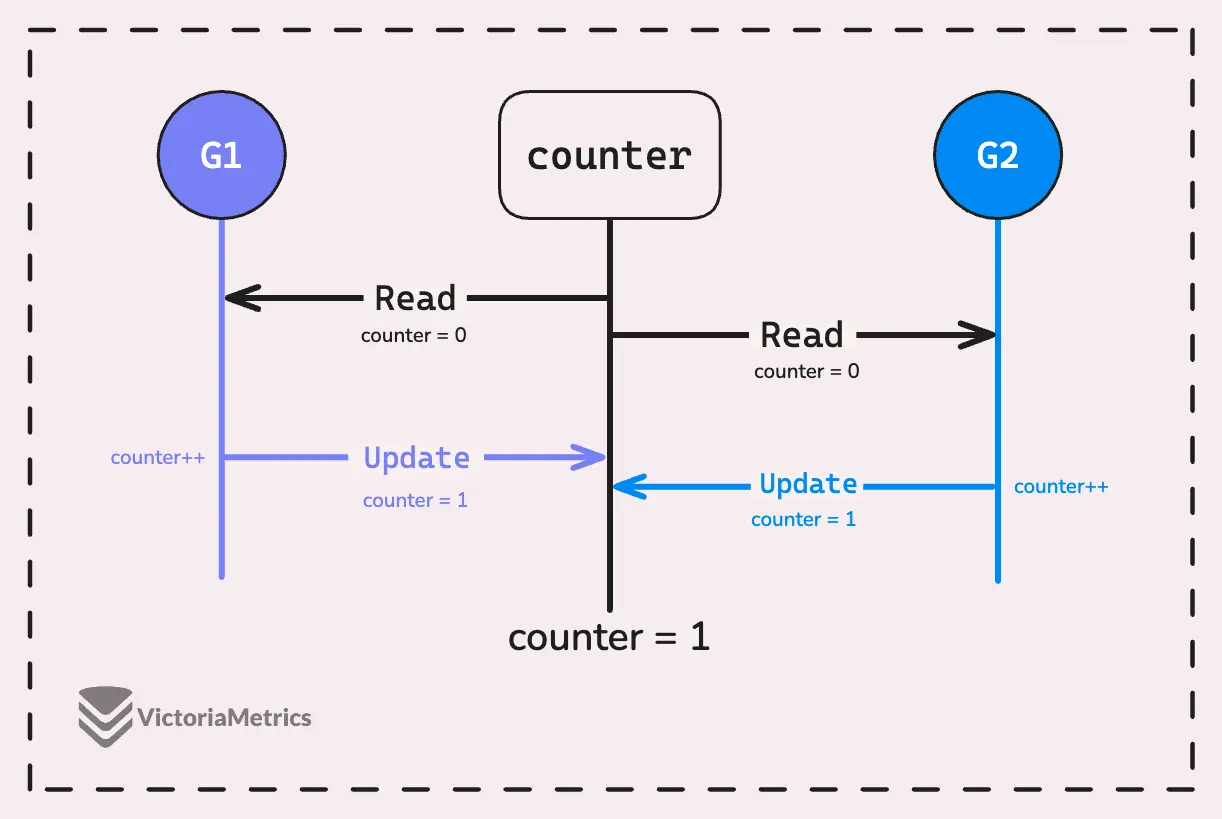

A race condition happens when multiple goroutines try to access and change shared data at the same time without proper synchronization. In this case, the increment operation (counter++) isn’t atomic.

It’s made up of multiple steps, below is the Go assembly code for counter++ in ARM64 architecture:

MOVD main.counter(SB), R0

ADD $1, R0, R0

MOVD R0, main.counter(SB)

The counter++ is a read-modify-write operation and these steps above aren’t atomic, meaning they’re not executed as a single, uninterruptible action.

For instance, goroutine G1 reads the value of counter, and before it writes the updated value, goroutine G2 reads the same value. Both then write their updated values back, but since they read the same original value, one increment is practically lost.

Using the atomic package is a good way to handle this, but today let’s focus on how a mutex solves this problem:

var counter = 0

var wg sync.WaitGroup

var mutex sync.Mutex

func incrementCounter() {

mutex.Lock()

counter++

mutex.Unlock()

wg.Done()

}

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 1000; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go incrementCounter()

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println(counter)

}

Now, the result is 1000, just as we expected. Using a mutex here is super straightforward: wrap the critical section with Lock and Unlock. But watch out, if you call Unlock on an already unlocked mutex, it’ll cause a fatal error sync: unlock of unlocked mutex.

It’s usually a good idea to use defer

mutex.Unlock()to ensure the unlock happens, even if something goes wrong. We’ve also got an article about Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps.

Also, you could set GOMAXPROCS to 1 by running runtime.GOMAXPROCS(1), and the result would still be correct at 1000. This is because our goroutines wouldn’t be running in parallel, and the function is simple enough not to be preempted while running.

Mutex Structure: The Anatomy

#

Before we dive into how the lock and unlock flow works in Go’s sync.Mutex, let’s break down the structure, or anatomy, of the mutex itself:

package sync

type Mutex struct {

state int32

sema uint32

}

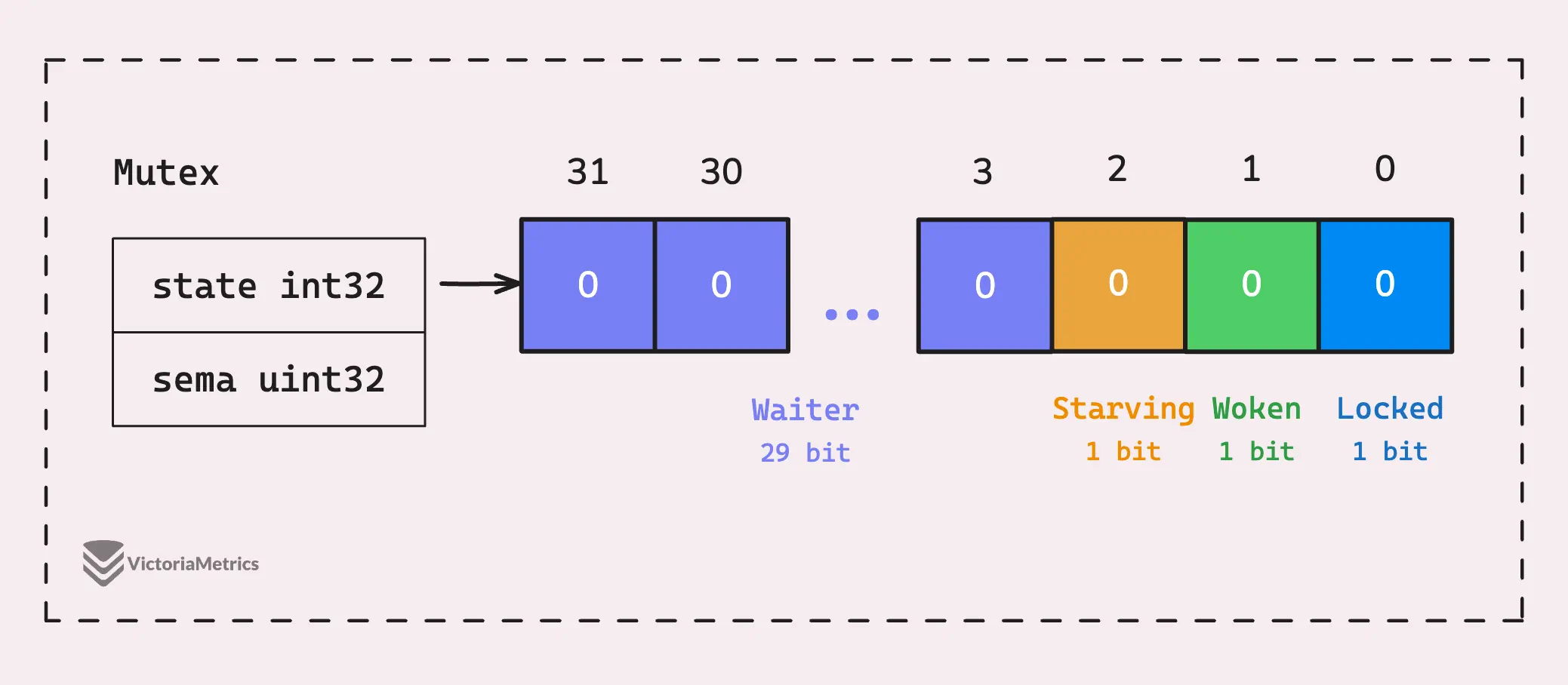

At its core, a mutex in Go has two fields: state and sema. They might look like simple numbers, but there’s more to them than meets the eye.

The state field is a 32-bit integer that shows the current state of the mutex. It’s actually divided into multiple bits that encode various pieces of information about the mutex.

Let’s make a rundown of state from the image:

- Locked (bit 0): Whether the mutex is currently locked. If it’s set to 1, the mutex is locked and no other goroutine can grab it.

- Woken (bit 1): Set to 1 if any goroutine has been woken up and is trying to acquire the mutex. Other goroutines shouldn’t be woken up unnecessarily.

- Starvation (bit 2): This bit shows if the mutex is in starvation mode (set to 1). We’ll dive into what this mode means in a bit.

- Waiter (bit 3-31): The rest of the bits keep track of how many goroutines are waiting for the mutex.

The other field, sema, is a uint32 that acts as a semaphore to manage and signal waiting goroutines. When the mutex is unlocked, one of the waiting goroutines is woken up to acquire the lock.

Unlike the state field, sema doesn’t have a specific bit layout and relies on runtime internal code to handle the semaphore logic.

Mutex Lock Flow

#

In the mutex.Lock function, there are two paths: the fast path for the usual case and the slow path for handling the unusual case.

func (m *Mutex) Lock() {

// Fast path: grab unlocked mutex.

if atomic.CompareAndSwapInt32(&m.state, 0, mutexLocked) {

if race.Enabled {

race.Acquire(unsafe.Pointer(m))

}

return

}

// Slow path (outlined so that the fast path can be inlined)

m.lockSlow()

}

The fast path is designed to be really quick and is expected to handle most lock acquisitions where the mutex isn’t already in use. This path is also inlined, meaning it’s embedded directly into the calling function:

$ go build -gcflags="-m"

./main.go:13:12: inlining call to sync.(*Mutex).Lock

./main.go:15:14: inlining call to sync.(*Mutex).Unlock

FYI, this inlined fast path is a neat trick that utilizes Go’s inline optimization, and it’s used a lot in Go’s source code.

When the CAS (Compare And Swap) operation in the fast path fails, it means the state field wasn’t 0, so the mutex is currently locked.

The real concern here is the slow path m.lockSlow, which does most of the heavy lifting. We won’t dive too deep into the source code since it requires a lot of knowledge about Go’s internal workings.

I’ll discuss the mechanism and maybe a bit of the internal code to keep things clear. In the slow path, the goroutine keeps actively spinning to try to acquire the lock, it doesn’t just go straight to the waiting queue.

“What do you mean by spinning?”

Spinning means the goroutine enters a tight loop, repeatedly checking the state of the mutex without giving up the CPU.

In this case, it is not a simple for loop but low-level assembly instructions to perform the spin-wait. Let’s take a quick peek at this code on ARM64 architecture:

TEXT runtime·procyield(SB),NOSPLIT,$0-0

MOVWU cycles+0(FP), R0

again:

YIELD

SUBW $1, R0

CBNZ R0, again

RET

The assembly code runs a tight loop for 30 cycles (runtime.procyield(30)), repeatedly yielding the CPU and decrementing the spin counter.

After spinning, it tries to acquire the lock again. If it fails, it has three more chances to spin before giving up. So, in total, it tries for up to 120 cycles. If it still can’t get the lock, it increases the waiter count, puts itself in the waiting queue, goes to sleep, waits for a signal to wake up and try again.

Why do we need spinning?

The idea behind spinning is to wait a short while in hopes that the mutex will free up soon, letting the goroutine grab the mutex without the overhead of a sleep-wake cycle.

If our computer doesn’t have multiple cores, spinning isn’t enabled because it would just waste CPU time.

“But what if another goroutine is already waiting for the mutex? It doesn’t seem fair if this goroutine takes the lock first.”

That’s why our mutex has two modes: Normal and Starvation mode. Spinning doesn’t work in Starvation mode.

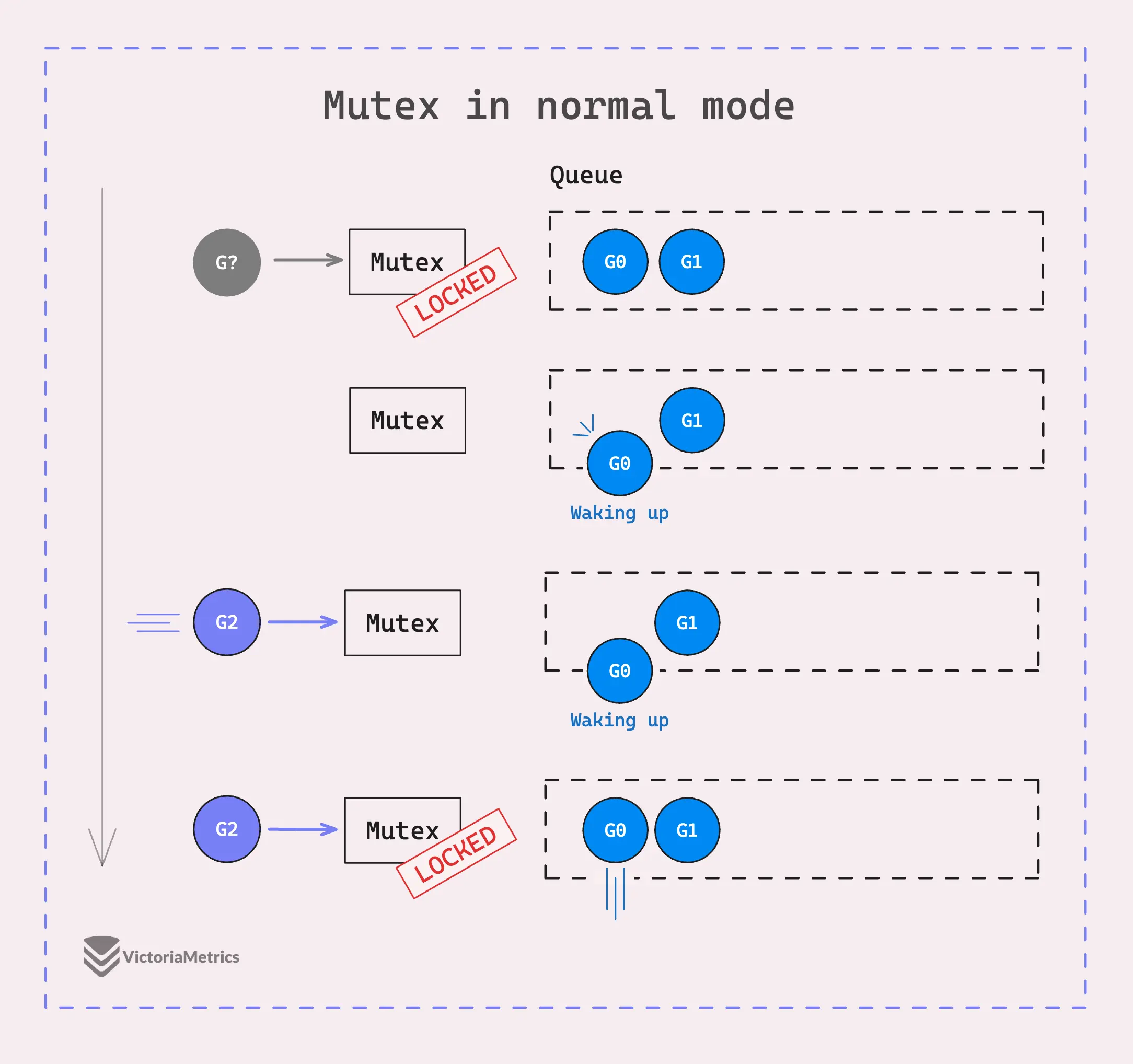

In normal mode, goroutines waiting for the mutex are organized in a first-in, first-out (FIFO) queue. When a goroutine wakes up to try and grab the mutex, it doesn’t get control immediately. Instead, it has to compete with any new goroutines that also want the mutex at that time.

This competition is tilted in favor of the new goroutines because they’re already running on the CPU and can quickly try to grab the mutex, while the queued goroutine is still waking up.

As a result, the goroutine that just woke up might frequently lose the race to the new contenders and get put back at the front of the queue.

“What if that goroutine is unlucky and always wakes up when a new goroutine arrives?”

Good question. If that happens, it never acquires the lock. That’s why we need to switch the mutex into starvation mode. There’s an issue #13086 that discussed the unfairness of the previous design.

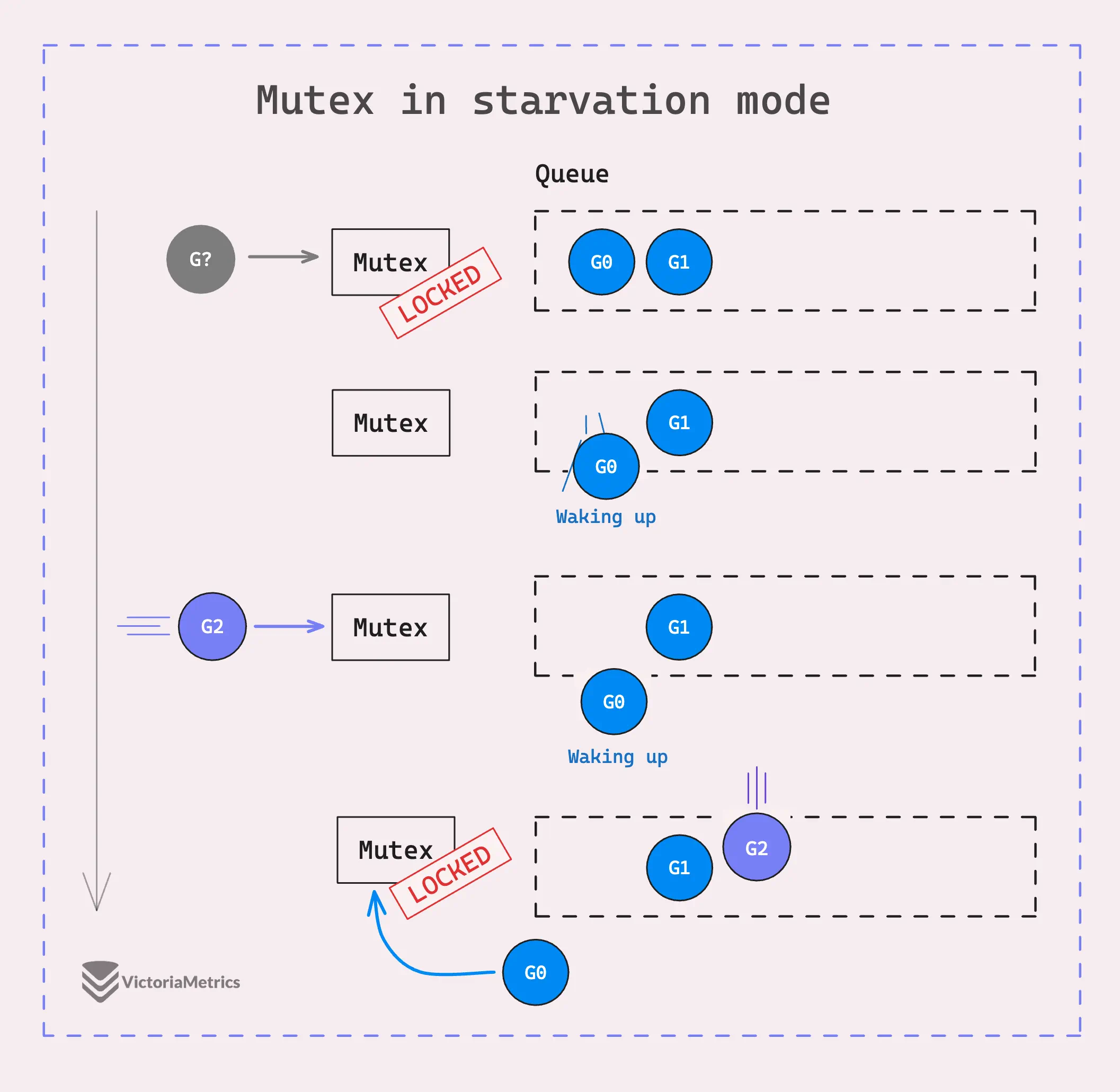

Starvation mode kicks in if a goroutine fails to acquire the lock for more than 1 millisecond. It’s designed to make sure that waiting goroutines eventually get a fair chance at the mutex.

In this mode, when a goroutine releases the mutex, it directly passes control to the goroutine at the front of the queue. This means no competition, no race, from new goroutines. They don’t even try to acquire it and just join the end of the waiting queue.

In the image above, the mutex continues giving the access to G1, G2, and so on. Each goroutine that has been waiting gets control and checks two conditions:

- If it is the last goroutine in the waiting queue.

- If it had to wait for less than one millisecond.

If either of these conditions is true, the mutex switches back to normal mode.

Mutex Unlock Flow

#

The unlock flow is simpler than the lock flow. We still have two paths: the fast path, which is inlined, and the slow path, which handles unusual cases.

The fast path drops the locked bit in the state of the mutex. If you remember the anatomy of a mutex, this is the first bit of mutex.state. If dropping this bit makes the state zero, it means no other flags are set (like waiting goroutines), and our mutex is now completely free.

But what if the state isn’t zero?

That’s where the slow path comes in and it needs to know if our mutex is in normal mode or starvation mode. Here’s a look at the slow path implementation:

func (m *Mutex) unlockSlow(new int32) {

// 1. Attempting to unlock an already unlocked mutex

// will cause a fatal error.

if (new+mutexLocked)&mutexLocked == 0 {

fatal("sync: unlock of unlocked mutex")

}

if new&mutexStarving == 0 {

old := new

for {

// 2. If there are no waiters, or if the mutex is already locked,

// or woken, or in starvation mode, return.

if old>>mutexWaiterShift == 0 || old&(mutexLocked|mutexWoken|mutexStarving) != 0 {

return

}

// Grab the right to wake someone.

new = (old - 1<<mutexWaiterShift) | mutexWoken

if atomic.CompareAndSwapInt32(&m.state, old, new) {

runtime_Semrelease(&m.sema, false, 1)

return

}

old = m.state

}

} else {

// 3. If the mutex is in starvation mode, hand off the ownership

// to the first waiting goroutine in the queue.

runtime_Semrelease(&m.sema, true, 1)

}

}

In normal mode, if there are waiters and no other goroutine has been woken or acquired the lock, the mutex tries to decrement the waiter count and turn on the mutexWoken flag atomically. If successful, it releases the semaphore to wake up one of the waiting goroutines to acquire the mutex.

In starvation mode, it atomically increments the semaphore (mutex.sem) and hands off mutex ownership directly to the first waiting goroutine in the queue. The second argument of runtime_Semrelease determines if the handoff is true.

And that’s all for today’s discussion. Thanks for joining us, and happy coding.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Inside Go’s Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus