- Blog /

- Go sync.Map: The Right Tool for the Right Job

Go sync.Map: The Right Tool for the Right Job

This post is part of a series about handling concurrency in Go:

- Go sync.Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- Go sync.WaitGroup and The Alignment Problem

- Go sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It

- Go sync.Cond, the Most Overlooked Sync Mechanism

- Go sync.Map: The Right Tool for the Right Job (We’re here)

- Go Sync.Once is Simple… Does It Really?

- Go Singleflight Melts in Your Code, Not in Your DB

A regular Go map isn’t concurrency safe when you’re reading and writing at the same time.

So, you’ll often see people using a combo of sync.Mutex or sync.RWMutex with a map to keep things in check. But should we jump to the conclusion that this setup is worse than sync.Map — a sync primitive built right into Go standard library?

Well, not really. In fact, both have their place depending on what you’re trying to do.

The thing to keep in mind is, sync.Map isn’t some magic replacement for all concurrent map scenarios. Most of the time, you’re probably better off sticking with a native Go map, combined with locking or other coordination strategies.

Now, if your service is dealing with more writes than reads, or if you need to do more complex operations that sync.Map just doesn’t handle well, you might actually see some performance dips—both in memory and CPU.

This happens because sync.Map is using two maps behind the scenes.

Another thing: with a regular map, you get better type safety. sync.Map, on the other hand, stores keys and values as interface{}, so you lose some of those type guarantees.

What is sync.Map?

#

So as we touched on earlier, using a regular map for concurrent access is risky business:

func main() {

m := make(map[string]int)

go func() {

for {

m["blog"] = 1

}

}()

go func() {

for {

fmt.Println(m["blog"])

}

}()

select{} // block-forever trick

}

// fatal error: concurrent map read and map write

Yeah, this crashes because Go doesn’t let you read and write to a regular map from multiple goroutines at the same time without throwing a fit.

Now, here’s where sync.Map steps in.

When you’ve got multiple goroutines reading or writing, sync.Map takes care of all that locking (or atomic operations) for you—so no manual locking needed, and no worrying about race conditions.

Plus, things like reading, writing, and deleting keys generally happen faster compared to a regular map with a mutex:

func main() {

var syncMap sync.Map

// store a key-value pair

syncMap.Store("blog", "VictoriaMetrics")

// load a value by key "blog"

value, ok := syncMap.Load("blog")

fmt.Println(value, ok)

// delete a key-value pair by key "blog"

syncMap.Delete("blog")

value, ok = syncMap.Load("blog")

fmt.Println(value, ok)

}

// Output:

// VictoriaMetrics true

// <nil> false

And there you go, sync.Map keeps things easy with simple operations, just like a regular map, but with concurrency handled behind the scenes.

When you write to a sync.Map, that write operation actually synchronizes before any future reads. So in Go’s memory model, once you write something, it’s guaranteed that subsequent reads will see those changes and there’s no way a goroutine will read old data before another goroutine finishes writing.

But what exactly does ‘read’ and ‘write’ mean here? Let’s break it down by looking at the methods sync.Map offers:

func (m *Map) Load(key any) (value any, ok bool)

func (m *Map) Store(key, value any)

func (m *Map) LoadOrStore(key, value any) (actual any, loaded bool)

func (m *Map) Delete(key any)

func (m *Map) LoadAndDelete(key any) (value any, loaded bool)

func (m *Map) CompareAndDelete(key, old any) (deleted bool)

func (m *Map) Swap(key, value any) (previous any, loaded bool)

func (m *Map) CompareAndSwap(key, old, new any) (swapped bool)

func (m *Map) Range(f func(key, value any) bool)

func (m *Map) Clear()

Here’s the lowdown on what these methods do:

Load,Store,Delete, andClear: These are the basics, and they work just like a regular Go map.Swap: This replaces the old value and returns what the previous value was. It’s also what powers the Store() method behind the scenes.LoadOrStore: This one’s handy — it checks if a key already exists. If it does, it returns the existing value without modifying anything, andloadedwill betrue. If the key doesn’t exist, it stores the new value and returns that, withloadedasfalse.LoadAndDelete: This tries to load a value by key, and if it exists, it removes the key from the map and returns the value.loadedwill betrueif the key was found and deleted, orfalseif it wasn’t there.CompareAndDeleteandCompareAndSwap: These are conditional. They’ll only delete or swap a key if its current value matches the old value. If the comparison succeeds, it removes or updates the key and returnstrue; otherwise, it does nothing and returnsfalse.Range(f): This is how you iterate through the map. It applies a functionfto each key-value pair. If the function returnsfalseat any point, the iteration stops, just likebreakin a for-loop.

All these methods are atomic, but Range is a bit of a special case.

Range doesn’t lock the map for the entire iteration and that means while you’re looping through the map, other goroutines can still add, update, or delete entries.

“So how does this help in a concurrent environment?”

We’ve all heard about how native maps can throw fatal errors if you try to read and write at the same time. But what a lot of people don’t realize is that even just iterating over a map isn’t safe when there’s concurrent access going on.

func main() {

m := make(map[string]int)

go func() {

for {

m["blog"] = 1

}

}()

go func() {

for {

for range m {

fmt.Println("iterating")

}

}

}()

select{} // block-forever trick

}

// fatal error: concurrent map iteration and map write

And that’s where sync.Map shines, right?

With sync.Map.Range, it’s designed to handle concurrent reads and writes during iteration without locking up the entire map. The trade-off, though, is that you might not get a perfectly consistent snapshot of the map while you’re iterating.

Now, I know some of you might be thinking: “Wait, isn’t something missing?”

Yes, there’s no Len() method for sync.Map to tell you how many entries it has. If you need that, you’ll have to roll your own solution using the Range method to count them up.

Also, sync.Map has gotten a little more feature-packed compared to earlier versions. If you’ve been using it for a while, you might notice some new additions, like the CompareAndDelete, CompareAndSwap, and Swap methods (introduced in Go 1.20). And then you’ve got Clear(), which were added in Go 1.23.

How sync.Map Works

#

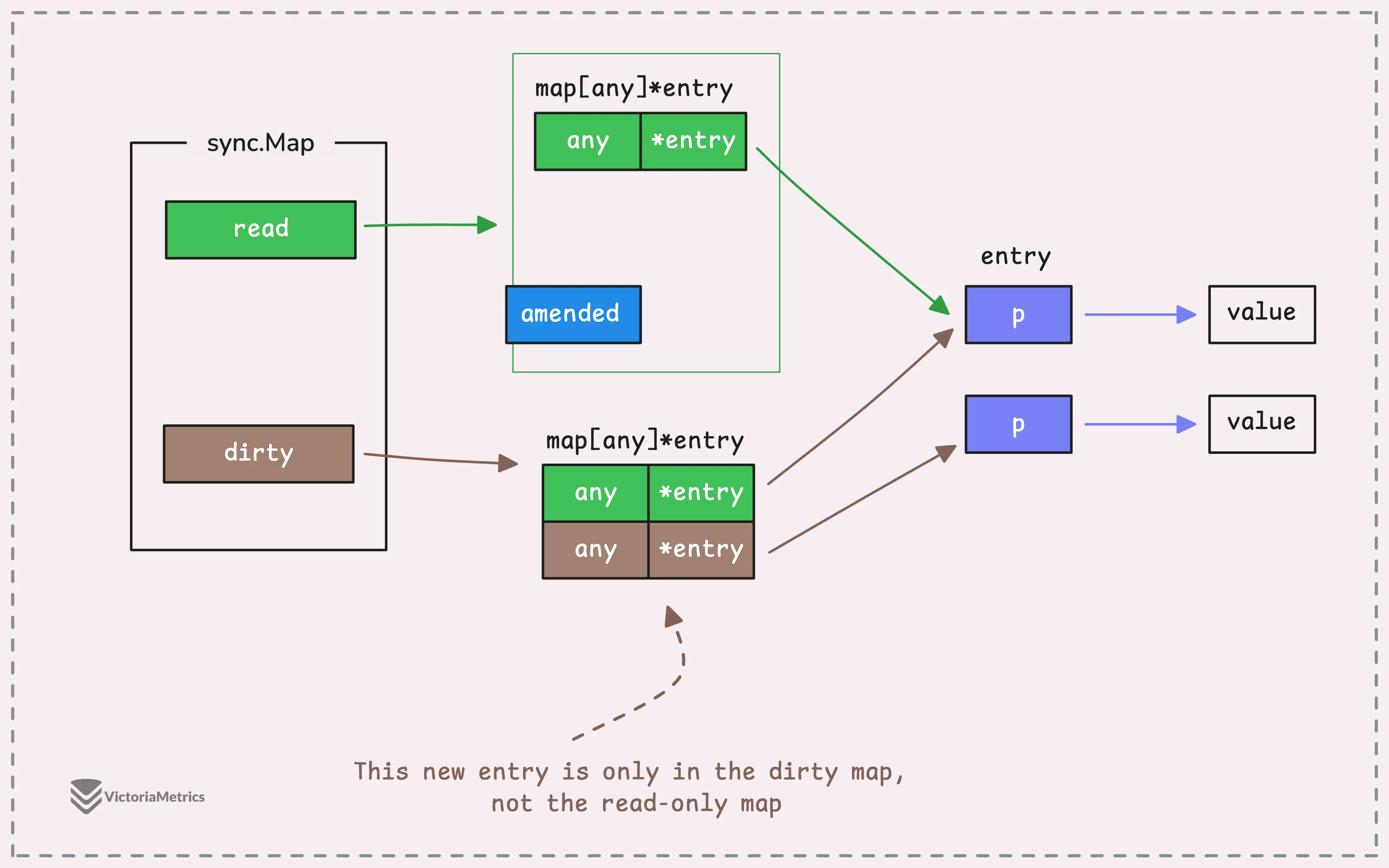

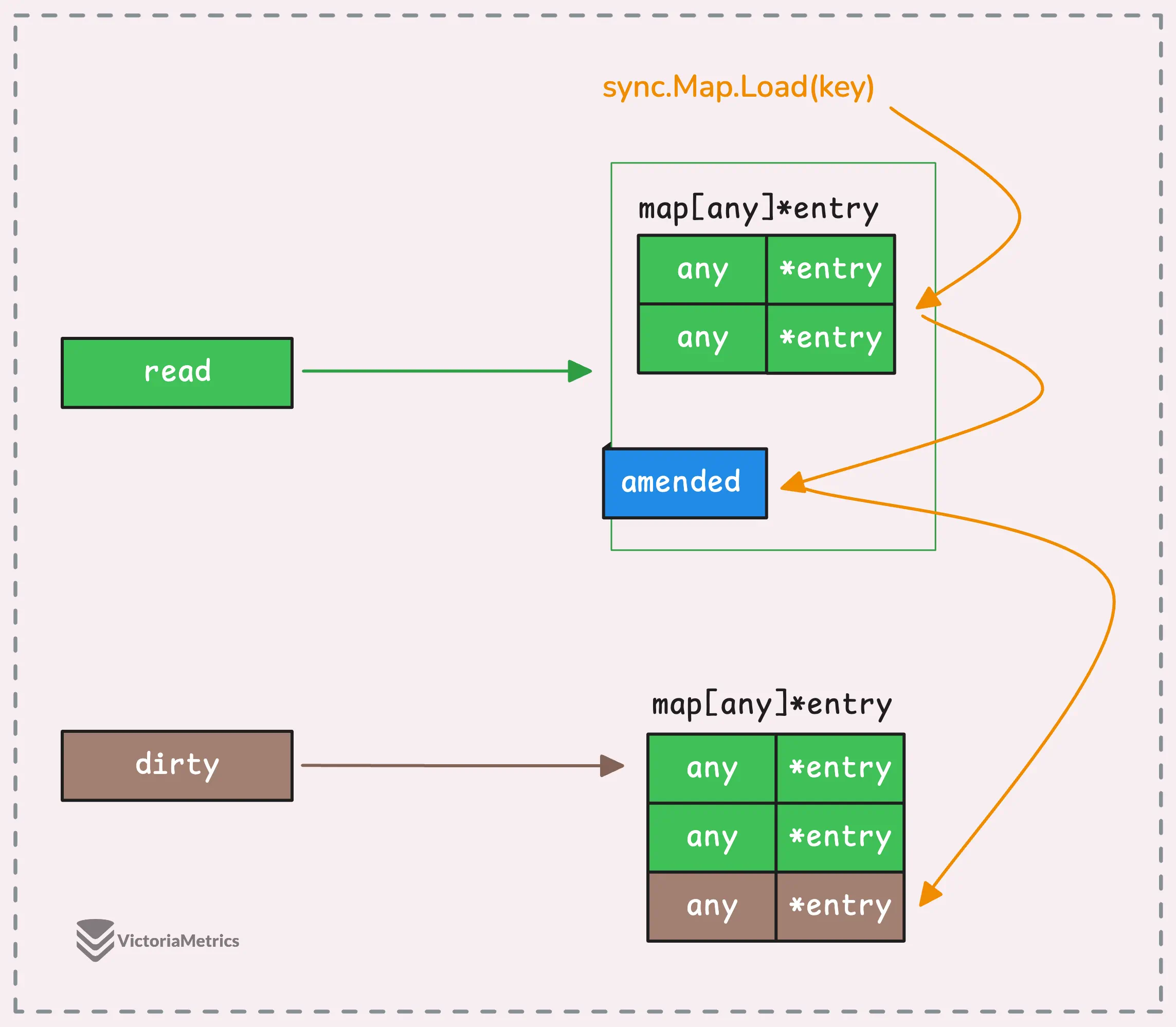

The magic behind sync.Map comes from its use of two separate native maps: the readonly map and the dirty map.

type Map struct {

mu Mutex

read atomic.Pointer[readOnly]

dirty map[any]*entry

misses int

}

The readonly map is where the fast, lock-free lookups happen.

It’s built around an atomic.Pointer, which lets multiple goroutines access it without needing to lock anything. This makes it ideal for scenarios where data is mostly being read and not frequently modified. But here’s the catch, the readonly map might not always hold the most up-to-date data, especially when new data has just been added.

That’s where the dirty map comes in.

The dirty map stores any new entries that get added while the readonly map is still being used for lookups. When you need to read or modify data that’s only in the dirty map, it requires using a mutex to prevent race conditions, as you can see from the structure of sync.Map, the dirty map is just a regular Go map without any built-in concurrency protection.

The readonly map has an extra trick up its sleeve: a flag (amended) that tells you if it’s out of date. If the flag is set to true, it means there’s at least one key-value pair in the dirty map that’s not in the readonly map yet.

type readOnly struct {

m map[any]*entry

amended bool // true if the dirty map contains some key not in m.

}

In short, sync.Map tries to keep the readonly map fast and lock-free, while the dirty map handles newer data, falling back to mutex locks in slow path.

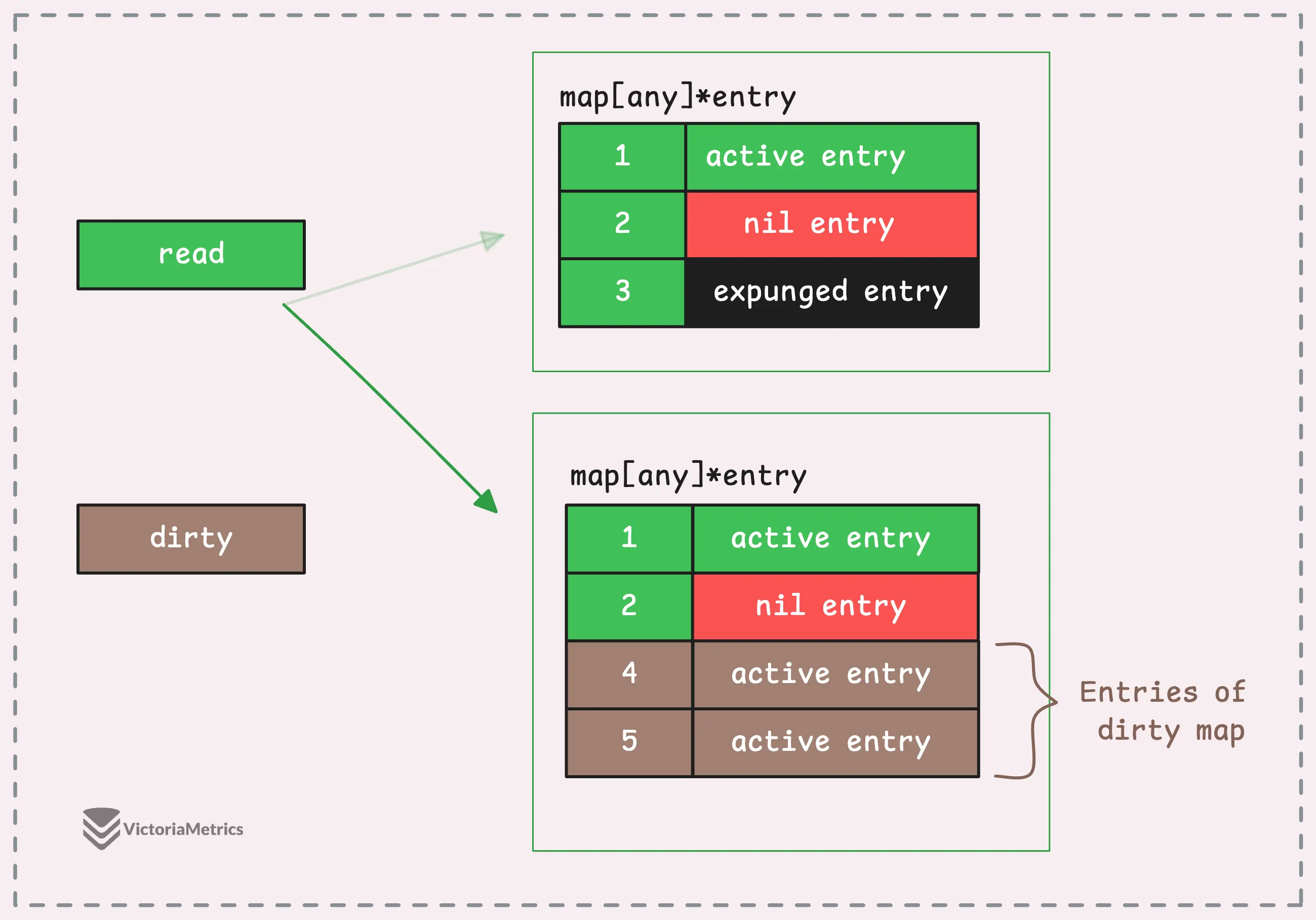

“So the dirty map is an expanded key-value store of the readonly map?”

Yes, but not exactly.

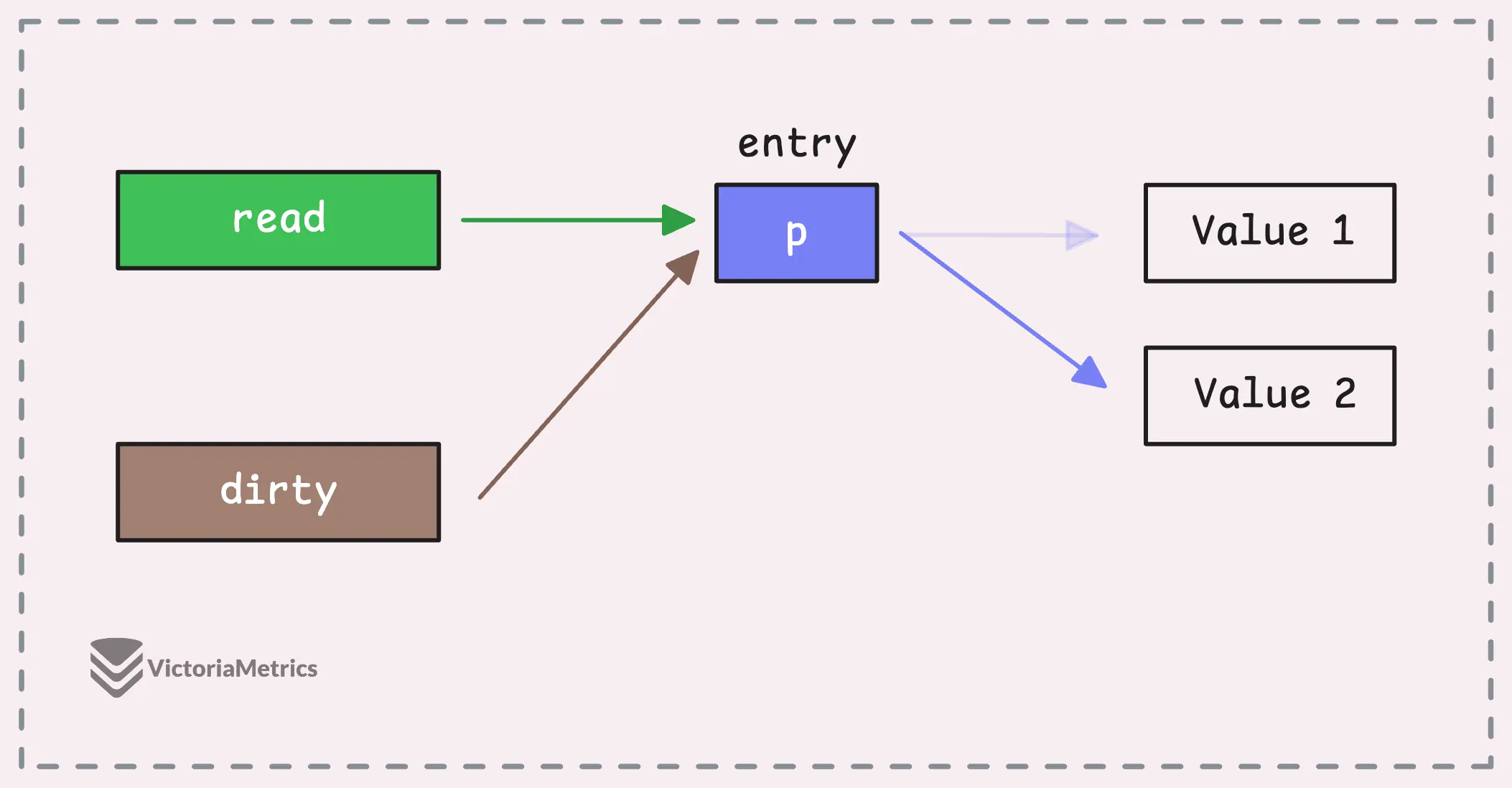

The dirty map contains all the data from the readonly map, along with any new entries that haven’t yet been promoted to the readonly map. However, this doesn’t mean you need to update both maps separately when you change a value in the readonly map or dirty map.

That’s because Go doesn’t store your value type directly in the map. Instead, Go uses a pointer to an entry struct to hold the value, which looks like this:

type entry struct {

p atomic.Pointer[any]

}

This entry struct contains a pointer (p) to the actual data.

So when you update a value, all you need to do is update this pointer. Since both the readonly and dirty maps point to the same entry, they’ll both see the updated value automatically.

It might seem simple struct, but there are some interesting details here.

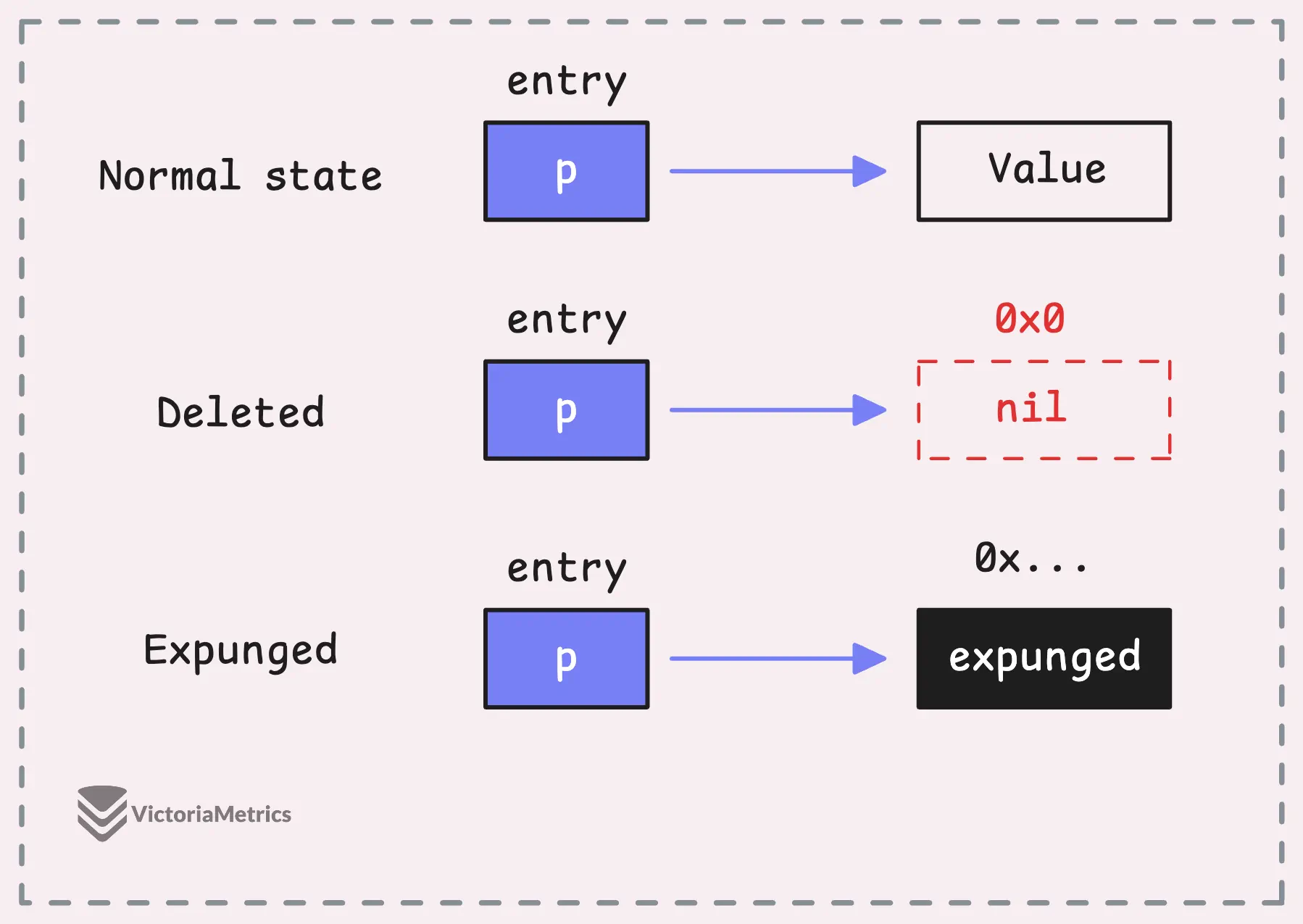

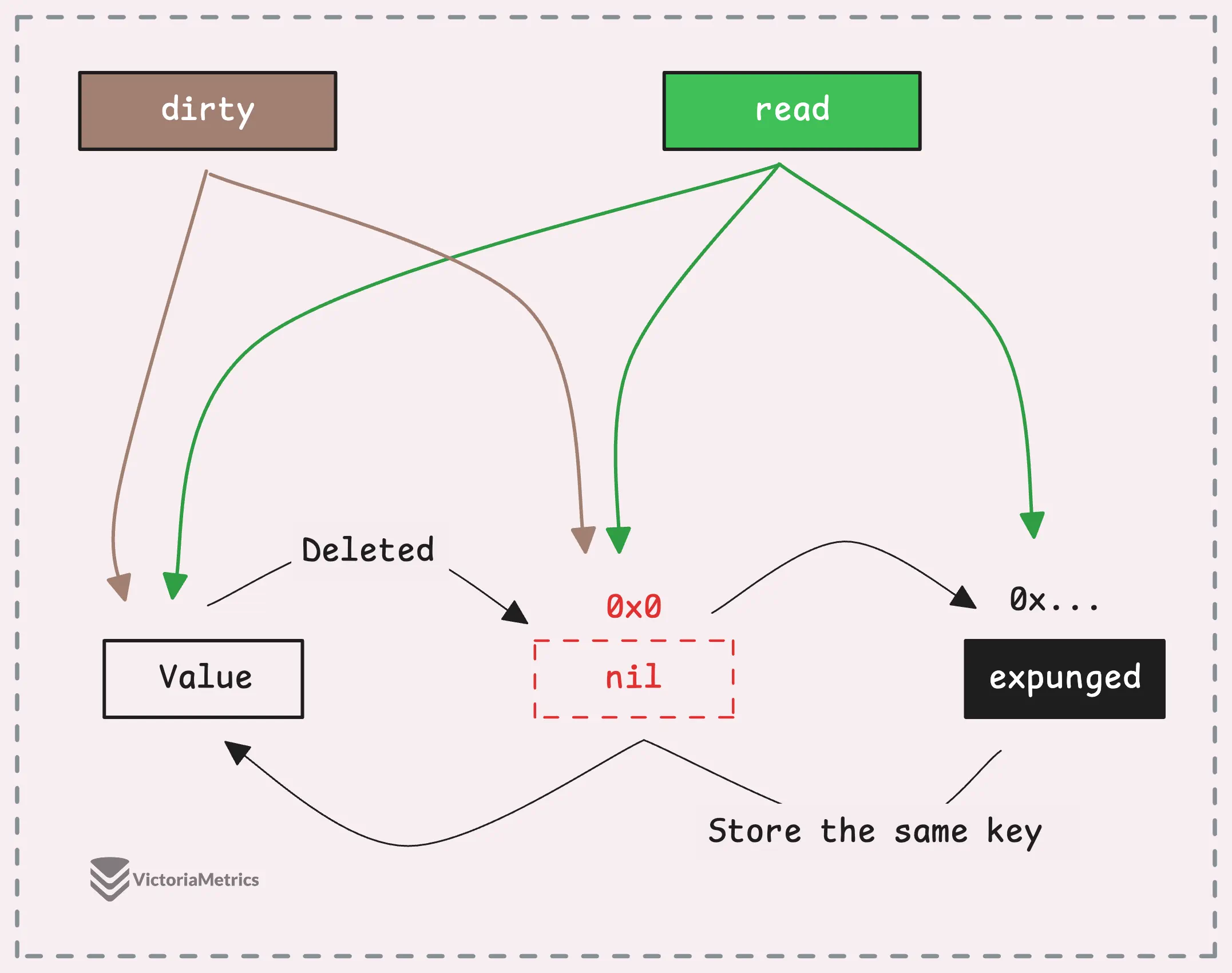

The behavior of the pointer in the entry struct defines the state of the entry in the map, and there are 3 possible states:

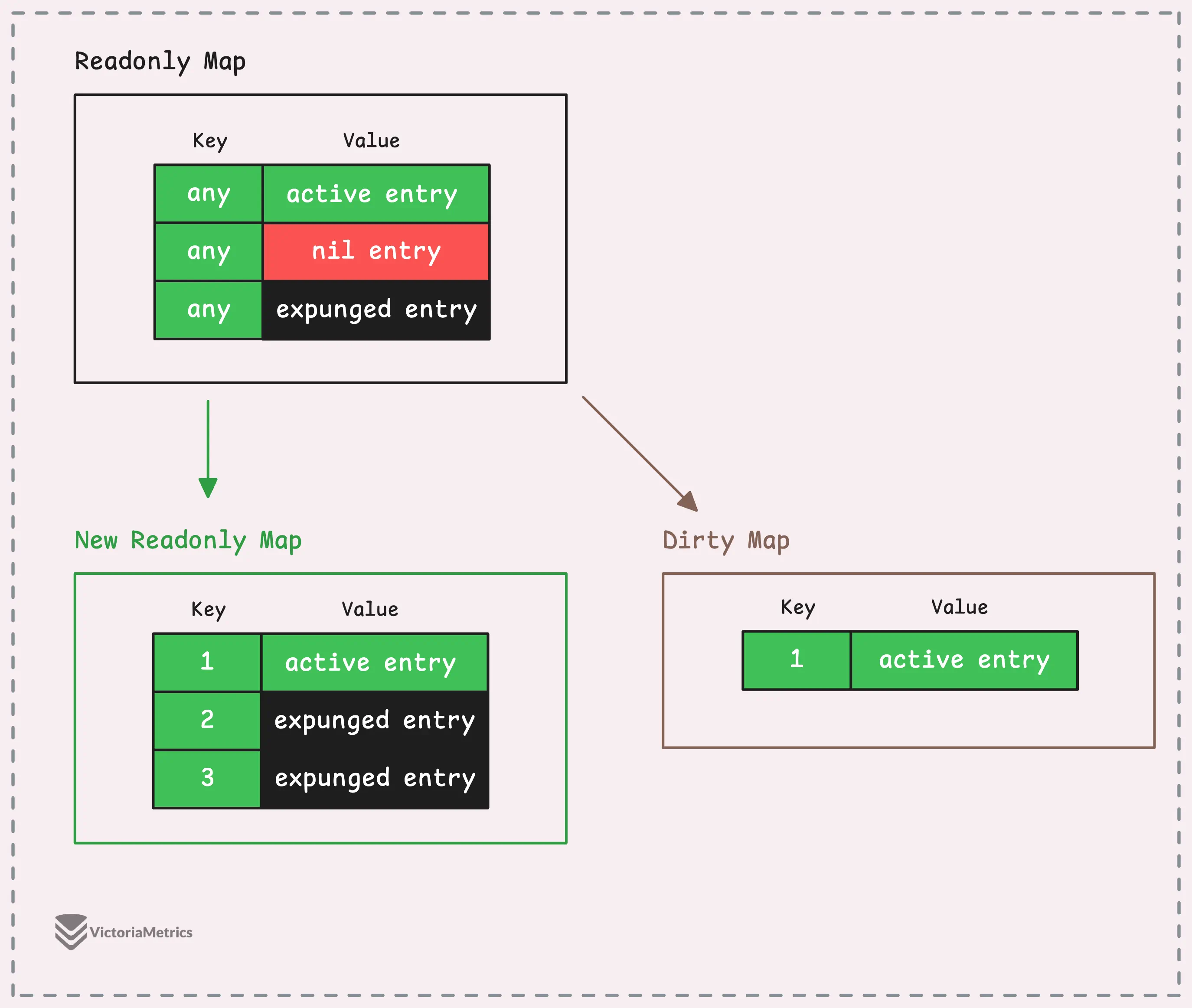

- Normal state: This is when the entry is valid. The pointer

pis pointing to a real value, and the entry exists in those maps, meaning it’s actively in use and can be read without any issues. - Deleted state: When an entry is deleted from a

sync.Map, it’s not immediately removed from the readonly maps. Instead, the pointerpis simply set tonil, signaling that the entry has been deleted but still exists in the maps. - Expunged state: This is a special state where the key is fully removed. The entry is marked with a special sentinel value that indicates it’s been completely deleted.

var expunged = new(any)

To break down the difference between these states, let’s go over their properties:

- Normal state: This is the active state. Both the readonly map and the dirty map share the same active entries, though the dirty map may contain more active entries than the readonly map. When an active entry is deleted, it transitions to the deleted state.

- Deleted state: An entry in the deleted state is shared between both the readonly and dirty maps. Internally, there’s a mechanism that eventually moves all deleted entries to the expunged state.

- Expunged state: Once an entry reaches the expunged state, it only exists in the readonly map, not the dirty map. When the dirty map is promoted to replace the readonly map (i.e.,

read = dirty), these expunged entries are completely removed. - Revival: Both deleted and expunged entries can be revived if the same key is added again. This means they return to the normal state and are active once more.

- A key can’t move directly from the normal state to the expunged state, or vice versa. It has to go through the deleted state first.

This concept might seem a bit complex, but as we dive deeper into the inner workings of sync.Map, we’ll explore how these state transitions happen and how sync.Map manages them.

Load: How sync.Map Loads Data & Promotes Dirty Map

#

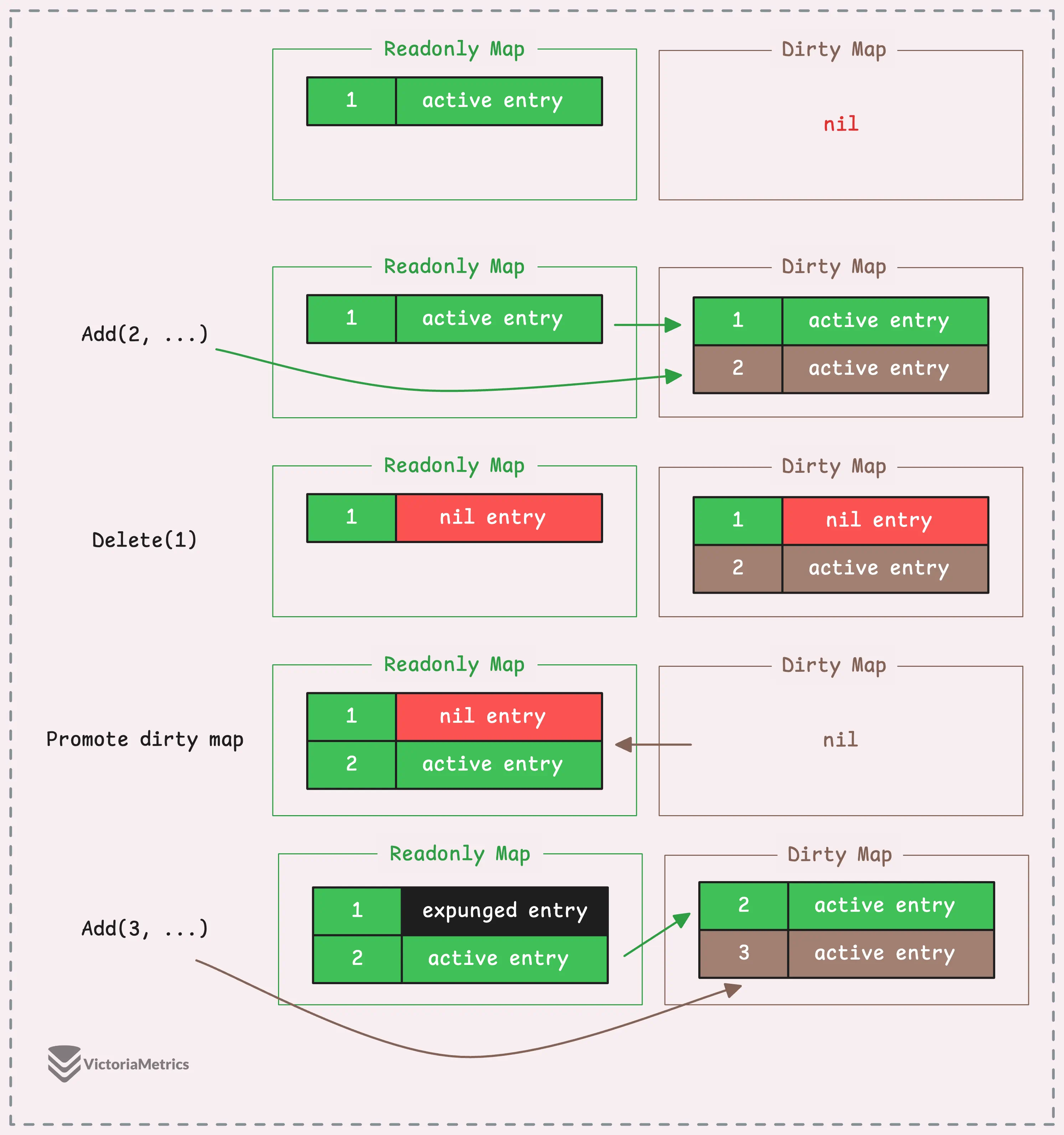

When you load (or get) data from a sync.Map, it always starts by checking the readonly map.

If the key is found there, great—you’re done, and the value is returned right away. But if the key isn’t found, things get a little more interesting. At this point, the system checks if the readonly map has been “amended”, meaning some data might be sitting in the dirty map.

Now we’re taking the slow path: sync.Map grabs a mutex and checks the dirty map to see if the key is there.

Every time the system has to go to the dirty map (whether it finds the data or not), it counts that as a “miss.” sync.Map keeps track of these misses with the map.misses counter.

If there are too many misses, it’s a signal that the readonly map is falling behind—it’s outdated and missing too many lookups. At that point, the system decides to promote the dirty map, meaning the dirty map becomes the new readonly map, and the old readonly map is replaced.

The dirty map then gets reset to nil.

Once the found key has been deleted (entry pointer set to nil or expunged), the load operation will ignore that entry and return like the key doesn’t exist, which makes sense as the key isn’t valid anymore.

The key takeaway here?

If you’re frequently adding new key-value pairs, the readonly map will eventually become outdated. When that happens, the system will have to keep falling back to the slow path to handle lookups many times, this triggers a lot of maintenance behind the scenes.

Store/Swap: Expunged State

#

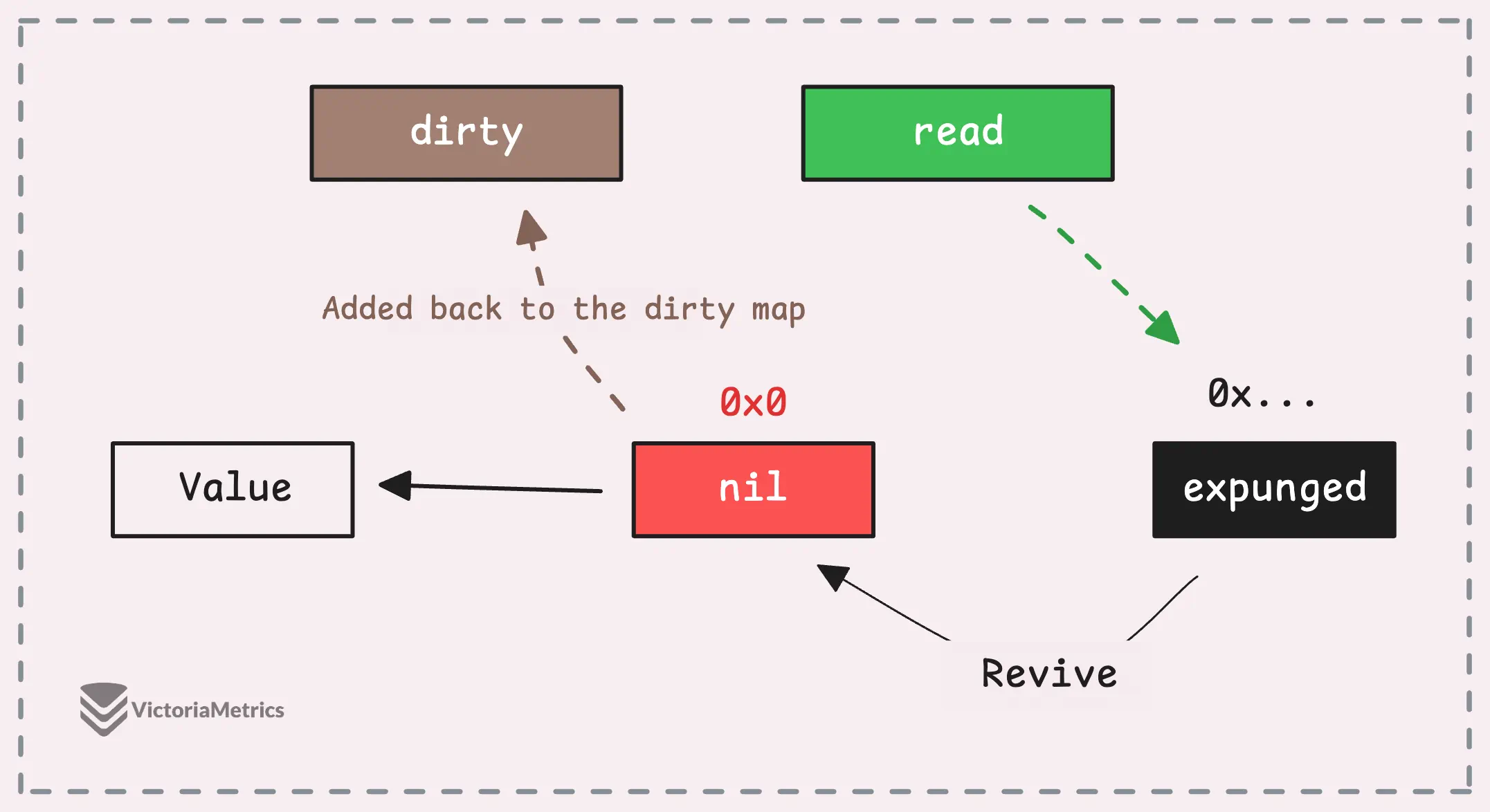

When you’re using Store (or Swap) in a sync.Map, it can either add a new key or update an existing one, depending on whether the key is already in those maps (It could be deleted but still exist in these maps).

Like with loading, there’s a fast path and a slow path.

If the key is luckily in the readonly map and hasn’t been expunged, it’s the fast path—everything happens without locking, and you’re good to go.

But if the key is in the readonly map and has been expunged, we have to ‘revive’ or unexpunge the key. This means we first set its pointer to nil and add it back to the dirty map before assigning the new value.

A deleted key can be in one of the following states as we discussed:

- Recently deleted: The pointer

pof entry is set tonil, meaning the key was deleted recently but still exists in both readonly and dirty map. - Expunged: This is when the key has been deleted for a while and is fully removed from the dirty map. Reviving an expunged key takes a bit more work compared to a recently deleted one because it’s no longer hanging around in the dirty map.

In short, expunged keys are more “gone” than recently deleted ones.

“Then why do we need the expunged state?”

There are two main reasons for the expunged state:

First, when a key is deleted, it’s represented by a nil pointer, but the key itself still exists in both the read and dirty maps. Over time, these “soft-deleted” keys can pile up and bloat the sync.Map, with no way to reclaim the space they take up.

That’s where the expunged state comes in, it serves as a middle phase that allows these entries to be cleaned up.

Once a key is marked as expunged, it only exists in the readonly map, and when the dirty map gets promoted to replace the readonly map, those expunged keys are fully removed.

Second, instead of removing those keys immediately from both maps, sync.Map takes a more lazy strategy, allowing them to be cleaned up in batches later on, instead of one-by-one.

“But when does a key go from the nil state to the expunged state?”

Now, to answer this, let’s get back to how storing operations flow.

If the key doesn’t exist in either the readonly or dirty maps, the new key-value pair gets added to the dirty map. This is something we’ve mentioned before, the readonly map isn’t always up to date, which is why new entries first land in the dirty map.

But what if the map was just promoted and the dirty map is currently nil?

As we mentioned earlier, the dirty map is an expanded version of the readonly map, including both old and new entries. In this stage, the entire readonly map is copied into the dirty map—except for the deleted keys (nil state & expunged state), then the nil entries will be marked as expunged.

func (m *Map) dirtyLocked() {

if m.dirty != nil {

return

}

read := m.loadReadOnly()

m.dirty = make(map[any]*entry, len(read.m))

for k, e := range read.m {

if !e.tryExpungeLocked() { // nil -> expunged

m.dirty[k] = e

}

}

}

After this, the dirty map is clean with no deleted keys and all the deleted keys in the readonly map have been marked as expunged.

If you’re still feeling a bit confused, the diagram below should help clarify things:

Delete: How sync.Map Deletes Data

#

When you need to delete a key-value pair from the readonly map, there’s no need to grab any locks.

Thanks to Go’s atomic package and a little spinlock trick, the pointer is updated to nil in a loop until it succeeds (or fails if another goroutine already deleted it).

This is done in a lock-free way:

func (e *entry) delete() (value any, ok bool) {

for {

p := e.p.Load()

if p == nil || p == expunged {

return nil, false

}

if e.p.CompareAndSwap(p, nil) {

return *p, true

}

}

}

In this code, e.p is the pointer for the entry in the readonly map. When we find the key-value pair, we try to set that pointer to nil—and if that works, the key is now in a “deleted” state.

Simple enough.

But what if the key-value pair is in the dirty map? That’s even easier. Instead of dealing with nil or expunged states, we can straight-up remove the entry from the dirty map using Go’s native delete(m, key) function. No fuss, no extra steps—just a clean removal from the map.

“Why not just set it to nil? It will eventually be expunged and removed by the system, right?”

The reason we don’t just rely on setting entry’s pointer to nil is that if you’re in a pattern where you’re constantly deleting and then storing keys—without triggering a Load(), the dirty map can bloat with entries.

The promotion of the dirty map to the readonly map is triggered by the misses counter, which goes up when you call Load() (or other LoadXXX methods).

So if you’re only deleting and storing, without any Load() operations, that promotion might never happen, and your dirty map will keep growing.

There’s actually an issue related to this: sync.Map keys will never be garbage collected. It shows that if your code focuses heavily on storing and deleting but doesn’t use Load() often, the dirty map can get bloated.

This kind of usage goes against the general recommendation for sync.Map, which is designed more for frequent reads.

And that’s is, we go through all the basic operations of sync.Map coressponding to the native map.

“How about other operations like Range()?”

Interestingly, though, Load() isn’t the only way to trigger promotion of the dirty map. The Range() operation can also do this.

When you use Range() to iterate over a sync.Map, it first checks if the readonly map is up-to-date. If the readonly map is fine, the iteration happens over that map.

But if the readonly map is outdated (amended), instead of dealing with both the readonly and dirty maps, the system promotes the dirty map to replace the readonly map, and then iterates over the promoted map.

You might be thinking: “Why not implement a Len() method that works the same way? Promote the dirty map and just return len(read)?”

Sounds logical, but it’s a bit more complicated than that.

Remember, both nil pointers and expunged entries (deleted keys) still hang around in the map, and they don’t count as actual data. You’d have to do extra work to filter out those deleted keys if you want an accurate count. Now, we go back to iterating over the map and counting the actual data.

Phew… that’s all for our discussion today. sync.Map is undoubtedly a great tool, but it can significantly increase your memory usage, as you’ve seen how many objects are created behind the scenes to maintain map stability and optimize for fast, read-heavy operations.

Happy mapping!

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus