- Blog /

- Go sync.Cond, the Most Overlooked Sync Mechanism

Go sync.Cond, the Most Overlooked Sync Mechanism

This post is part of a series about handling concurrency in Go:

- Go sync.Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- Go sync.WaitGroup and The Alignment Problem

- Go sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It

- Go sync.Cond, the Most Overlooked Sync Mechanism (We’re here)

- Go sync.Map: The Right Tool for the Right Job

- Go Sync.Once is Simple… Does It Really?

- Go Singleflight Melts in Your Code, Not in Your DB

In Go, sync.Cond is a synchronization primitive, though it’s not as commonly used as its siblings like sync.Mutex or sync.WaitGroup. You’ll rarely see it in most projects or even in the standard libraries, where other sync mechanisms tend to take its place.

That said, as a Go engineer, you don’t really want to find yourself reading through code that uses sync.Cond and not have a clue what’s going on, because it is part of the standard library, after all.

So, this discussion will help you close that gap, and even better, it’ll give you a clearer sense of how it actually works in practice.

What is sync.Cond?

#

So, let’s break down what sync.Cond is all about.

When a goroutine needs to wait for something specific to happen, like some shared data changing, it can “block,” meaning it just pauses its work until it gets the go-ahead to continue. The most basic way to do this is with a loop, maybe even adding a time.Sleep to prevent the CPU from going crazy with busy-waiting.

Here’s what that might look like:

// wait until condition is true

for !condition {

}

// or

for !condition {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

}

Now, this isn’t really efficient as that loop is still running in the background, burning through CPU cycles, even when nothing’s changed.

That’s where sync.Cond steps in, a better way to let goroutines coordinate their work. Technically, it’s a “condition variable” if you’re coming from a more academic background.

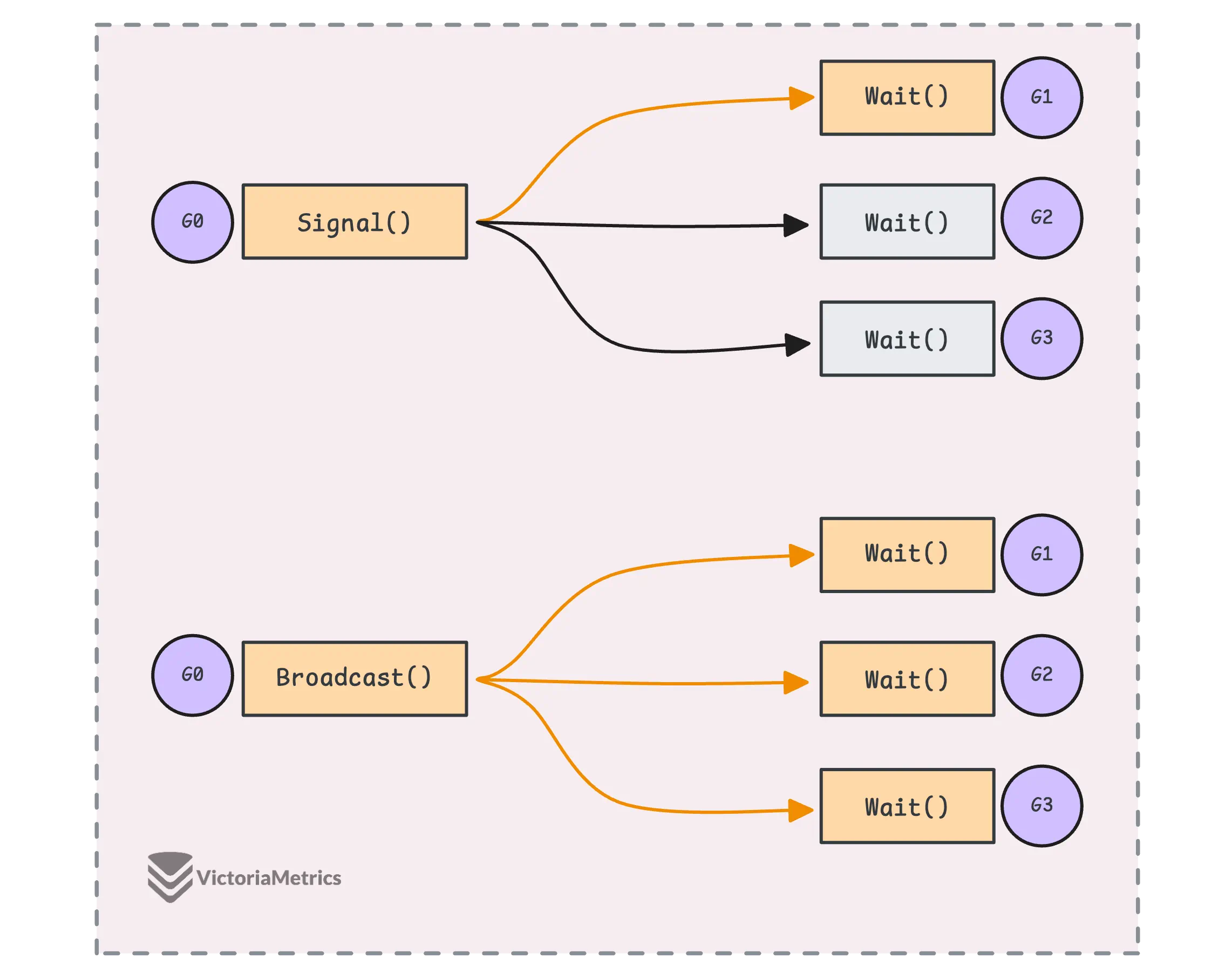

- When one goroutine is waiting for something to happen (waiting for a certain condition to become true), it can call

Wait(). - Another goroutine, once it knows that the condition might be met, can call

Signal()orBroadcast()to wake up the waiting goroutine(s) and let them know it’s time to move on.

Here’s the basic interface sync.Cond provides:

// Suspends the calling goroutine until the condition is met

func (c *Cond) Wait() {}

// Wakes up one waiting goroutine, if there is one

func (c *Cond) Signal() {}

// Wakes up all waiting goroutines

func (c *Cond) Broadcast() {}

Alright, let’s check out a quick pseudo-example. This time, we’ve got a Pokémon theme going on, imagine we’re waiting for a specific Pokémon, and we want to notify other goroutines when it shows up.

var pokemonList = []string{"Pikachu", "Charmander", "Squirtle", "Bulbasaur", "Jigglypuff"}

var cond = sync.NewCond(&sync.Mutex{})

var pokemon = ""

func main() {

// Consumer

go func() {

cond.L.Lock()

defer cond.L.Unlock()

// waits until Pikachu appears

for pokemon != "Pikachu" {

cond.Wait()

}

println("Caught" + pokemon)

pokemon = ""

}()

// Producer

go func() {

// Every 1ms, a random Pokémon appears

for i := 0; i < 100; i++ {

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond)

cond.L.Lock()

pokemon = pokemonList[rand.Intn(len(pokemonList))]

cond.L.Unlock()

cond.Signal()

}

}()

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond) // lazy wait

}

// Output:

// Caught Pikachu

In this example, one goroutine is waiting for Pikachu to show up, while another one (the producer) randomly selects a Pokémon from the list and signals the consumer when a new one appears.

When the producer sends the signal, the consumer wakes up and checks if the right Pokémon has appeared. If it has, we catch the Pokémon, if not, the consumer goes back to sleep and waits for the next one.

The problem is, there’s a gap between the producer sending the signal and the consumer actually waking up. In the meantime, the Pokémon could change, because the consumer goroutine might wake up later than 1ms (rarely) or other goroutine modifies the shared pokemon. So sync.Cond is basically saying: ‘Hey, something changed! Wake up and check it out, but if you’re too late, it might change again.’

If the consumer wakes up late, the Pokémon might run away, and the goroutine will go back to sleep.

“Huh, I could use a channel to send the pokemon name or signal to the other goroutine”

Absolutely. In fact, channels are generally preferred over sync.Cond in Go because they’re simpler, more idiomatic, and familiar to most developers.

In the case above, you could easily send the Pokémon name through a channel, or just use an empty struct{} to signal without sending any data. But our issue isn’t just about passing messages through channels, it’s about dealing with a shared state.

Our example is pretty simple, but if multiple goroutines are accessing the shared pokemon variable, let’s look at what happens if we use a channel:

- If we use a channel to send the Pokémon name, we’d still need a mutex to protect the shared pokemon variable.

- If we use a channel just to signal, a mutex is still necessary to manage access to the shared state.

- If we check for Pikachu in the producer and then send it through the channel, we’d also need a mutex. On top of that, we’d violate the separation of concerns principle, where the producer is taking on the logic that really belongs to the consumer.

That said, when multiple goroutines are modifying shared data, a mutex is still necessary to protect it. You’ll often see a combination of channels and mutexes in these cases to ensure proper synchronization and data safety.

“Okay, but what about broadcasting signals?”

Good question! You can indeed mimic a broadcast signal to all waiting goroutines using a channel by simply closing it (close(ch)). When you close a channel, all goroutines receiving from that channel get notified. But keep in mind, a closed channel can’t be reused, once it’s closed, it stays closed.

By the way, there’s actually been talk about removing sync.Cond in Go 2: proposal: sync: remove the Cond type.

“So, what’s sync.Cond good for, then?”

Well, there are certain scenarios where sync.Cond can be more appropriate than channels.

- With a channel, you can either send a signal to one goroutine by sending a value or notify all goroutines by closing the channel, but you can’t do both.

sync.Condgives you more fine-grained control. You can call Signal() to wake up a single goroutine orBroadcast()to wake up all of them. - And you can call

Broadcast()as many times as you need, which channels can’t do once they’re closed (closing a closed channel will trigger a panic). - Channels don’t provide a built-in way to protect shared data—you’d need to manage that separately with a mutex. sync.Cond, on the other hand, gives you a more integrated approach by combining locking and signaling in one package (and better performance).

“Why is the Lock embedded in sync.Cond?”

In theory, a condition variable like sync.Cond doesn’t have to be tied to a lock for its signaling to work.

You could have the users manage their own locks outside of the condition variable, which might sound like it gives more flexibility. It’s not really a technical limitation but more about human error.

Managing it manually can easily lead to mistakes because the pattern isn’t really intuitive, you have to unlock the mutex before calling Wait(), then lock it again when the goroutine wakes up. This process can feel awkward and is pretty prone to errors, like forgetting to lock or unlock at the right time.

But why does the pattern seem a little off?

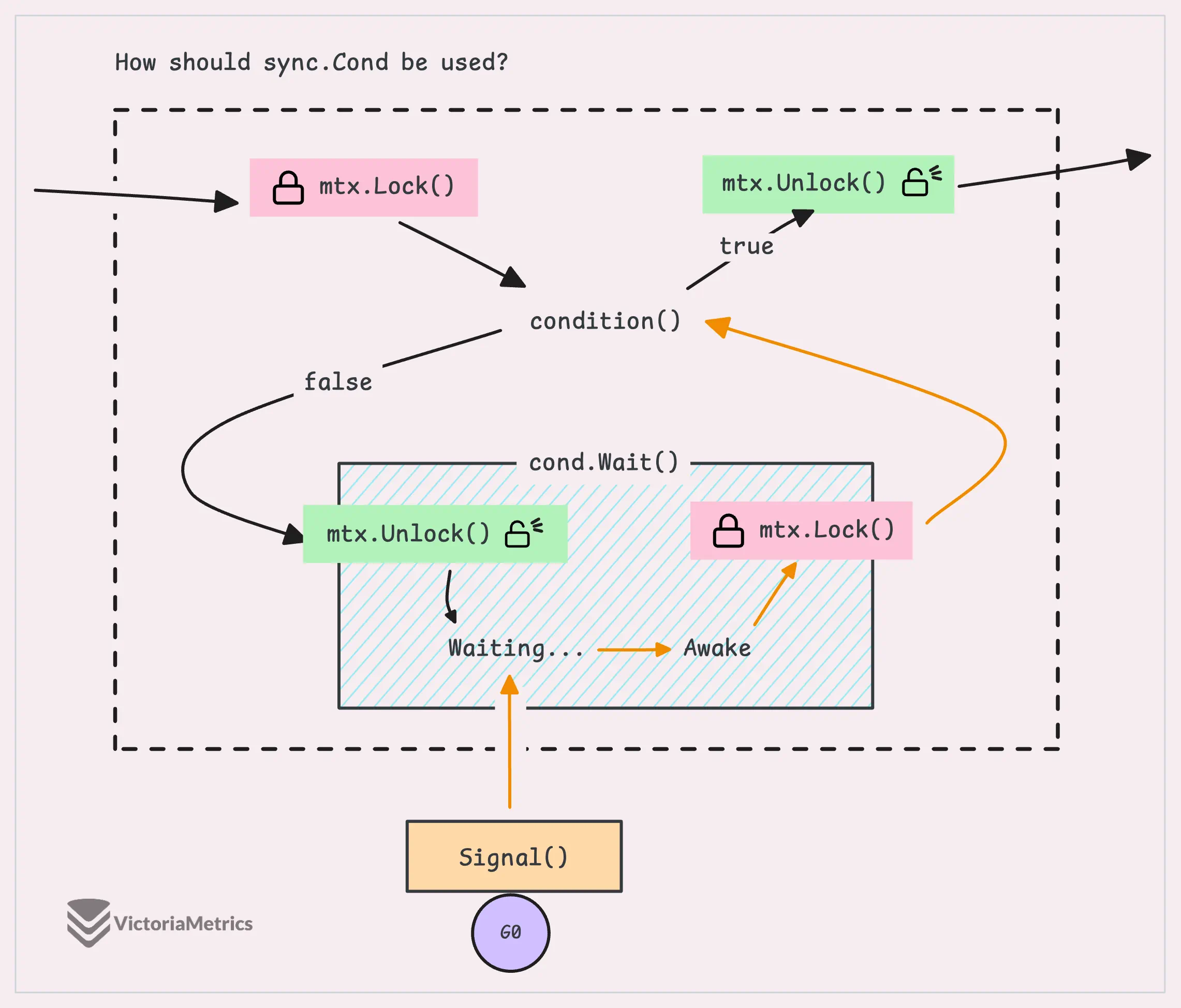

Typically, goroutines that call cond.Wait() need to check some shared state in a loop, like this:

for !checkSomeSharedState() {

cond.Wait()

}

The lock embedded in sync.Cond helps handle the lock/unlock process for us, making the code cleaner and less error-prone, we will discuss the pattern in detail soon.

How to use it?

#

If you look closely at the previous example, you’ll notice a consistent pattern in consumer: we always lock the mutex before waiting (.Wait()) on the condition, and we unlock it after the condition is met.

Plus, we wrap the waiting condition inside a loop, here’s a refresher:

// Consumer

go func() {

cond.L.Lock()

defer cond.L.Unlock()

// waits until Pikachu appears

for pokemon != "Pikachu" {

cond.Wait()

}

println("Caught" + pokemon)

}()

Cond.Wait()

#

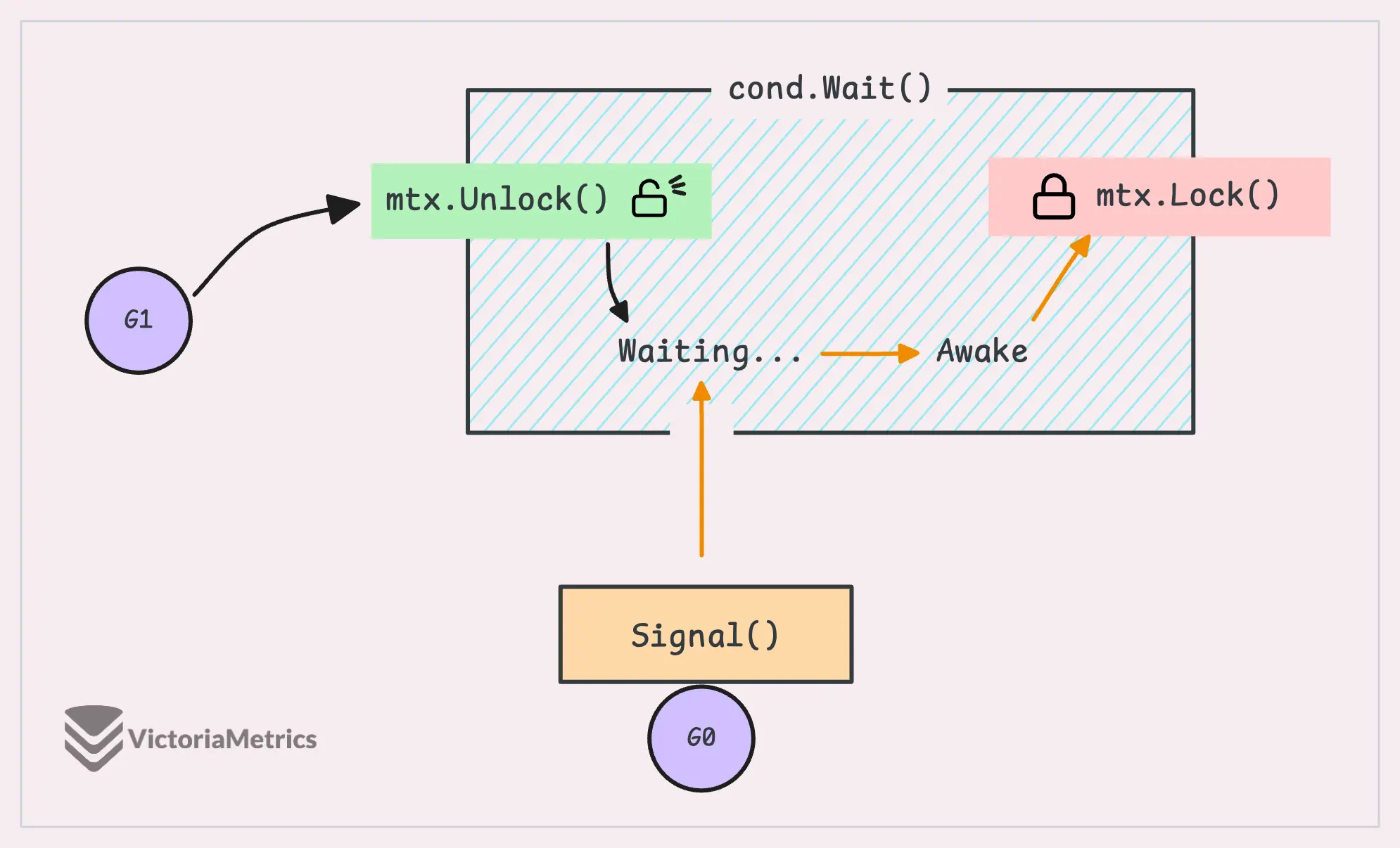

When we call Wait() on a sync.Cond, we’re telling the current goroutine to hang tight until some condition is met.

Here’s what’s happening behind the scenes:

- The goroutine gets added to a list of other goroutines that are also waiting on this same condition. All these goroutines are blocked, meaning they can’t continue until they’re “woken up” by either a

Signal()orBroadcast()call. - The key part here is that the mutex must be locked before calling

Wait()becauseWait()does something important, it automatically releases the lock (callsUnlock()) before putting the goroutine to sleep. This allows other goroutines to grab the lock and do their work while the original goroutine is waiting. - When the waiting goroutine gets woken up (by

Signal()orBroadcast()), it doesn’t immediately resume work. First, it has to re-acquire the lock (Lock()).

Here’s a look at how Wait() works under the hood:

func (c *Cond) Wait() {

// Check if Cond has been copied

c.checker.check()

// Get the ticket number

t := runtime_notifyListAdd(&c.notify)

// Unlock the mutex

c.L.Unlock()

// Suspend the goroutine until being woken up

runtime_notifyListWait(&c.notify, t)

// Re-lock the mutex

c.L.Lock()

}

Even though it’s simple, we can take away 4 main points:

- There’s a checker to prevent copying the

Condinstance, it would be panic if you do so. - Calling

cond.Wait()immediately unlocks the mutex, so the mutex must be locked before callingcond.Wait(), otherwise, it will panic. - After being woken up,

cond.Wait()re-locks the mutex, which means you’ll need to unlock it again after you’re done with the shared data. - Most of

sync.Cond’s functionality is implemented in the Go runtime with an internal data structure callednotifyList, which uses a ticket-based system for notifications.

Because of this lock/unlock behavior, there’s a typical pattern you’ll follow when using sync.Cond.Wait() to avoid common mistakes:

c.L.Lock()

for !condition() {

c.Wait()

}

// ... make use of condition ...

c.L.Unlock()

“Why not just use

c.Wait()directly without a loop?”

When Wait() returns, we can’t just assume that the condition we’re waiting for is immediately true. While our goroutine is waking up, other goroutines could’ve messed with the shared state and the condition might not be true anymore. So, to handle this properly, we always want to use Wait() inside a loop.

We also mentioned this delay issue in the Pokémon example.

The loop keeps things in check by continuously testing the condition, and only when that condition is true does your goroutine move forward.

Cond.Signal() & Cond.Broadcast()

#

The Signal() method is used to wake up one goroutine that’s currently waiting on a condition variable.

- If there are no goroutines currently waiting,

Signal()doesn’t do anything, it’s basically a no-op in that case. - If there are goroutines waiting,

Signal()wakes up the first one in the queue. So if you’ve fired off a bunch of goroutines, like from 0 to n, the 0th goroutine will be the first one woken up by theSignal()call.

Let’s walk through a quick example:

func main() {

cond := sync.NewCond(&sync.Mutex{})

for i := range 10 {

go func(i int) {

cond.L.Lock()

defer cond.L.Unlock()

cond.Wait()

fmt.Println(i)

}(i)

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond)

}

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond) // wait for goroutines to be ready

cond.Signal()

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond) // wait for goroutines to be woken up

}

// Output:

// 0

The idea here is that Signal() is used to wake up one goroutine and tell it that the condition might be satisfied. Here’s what the Signal() implementation looks like:

func (c *Cond) Signal() {

c.checker.check()

runtime_notifyListNotifyOne(&c.notify)

}

You don’t have to lock the mutex before calling Signal(), but it’s generally a good idea to do so, especially if you’re modifying shared data and it’s being accessed concurrently.

How about cond.Broadcast()?

func (c *Cond) Broadcast() {

c.checker.check()

runtime_notifyListNotifyAll(&c.notify)

}

When you call Broadcast(), it wakes up all the waiting goroutines and removes them from the queue. The internal logic here is still pretty simple, hidden behind the runtime_notifyListNotifyAll() function.

func main() {

cond := sync.NewCond(&sync.Mutex{})

for i := range 10 {

go func(i int) {

cond.L.Lock()

defer cond.L.Unlock()

cond.Wait()

fmt.Println(i)

}(i)

}

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond) // wait for goroutines to be ready

cond.Broadcast()

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond) // wait for goroutines to be woken up

}

// Output:

// 8

// 6

// 3

// 2

// 4

// 5

// 1

// 0

// 9

// 7

This time, all the goroutines are woken up within the 100 milliseconds, but there’s no specific order to how they’re woken up.

When Broadcast() is called, it marks all the waiting goroutines as ready to run, but they don’t run immediately, they’re picked based on the Go scheduler’s underlying algorithm, which can be a bit unpredictable.

How It Works Internally

#

In all our Go blog posts, we like to include a section on how things work under the hood. It’s always helpful to understand the reasoning behind design choices and what kind of problems they’re trying to solve.

Copy checker

#

The copy checker (copyChecker) in the sync package is designed to catch if a Cond object has been copied after it’s been used for the first time. The “first time” could be any of the public methods like Wait(), Signal(), or Broadcast().

If the Cond gets copied after that first use, the program will panic with the error: “sync.Cond is copied”.

You might have seen something similar in sync.WaitGroup or sync.Pool, where they use a noCopy field to prevent copying, but in those cases, it just avoids the issue without causing a panic.

Now, this copyChecker is actually just a uintptr, which is basically an integer that holds a memory address, here’s how it works:

- After the first time you use

sync.Cond, thecopyCheckerstores the memory address of itself, basically pointing to thecond.copyCheckerobject. - If the object gets copied, the memory address of the copy checker (

&cond.copyChecker) changes (since the new copy lives in a different location in memory), but theuintptrthat the copy checker holds doesn’t change.

The check is simple: compare the memory addresses. If they’re different, boom, there’s a panic.

Even though this logic is simple, the implementation might seem a bit tricky if you’re not familiar with Go’s atomic operations and the unsafe package.

// copyChecker holds back pointer to itself to detect object copying.

type copyChecker uintptr

func (c *copyChecker) check() {

if uintptr(*c) != uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(c)) &&

!atomic.CompareAndSwapUintptr((*uintptr)(c), 0, uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(c))) &&

uintptr(*c) != uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(c)) {

panic("sync.Cond is copied")

}

}

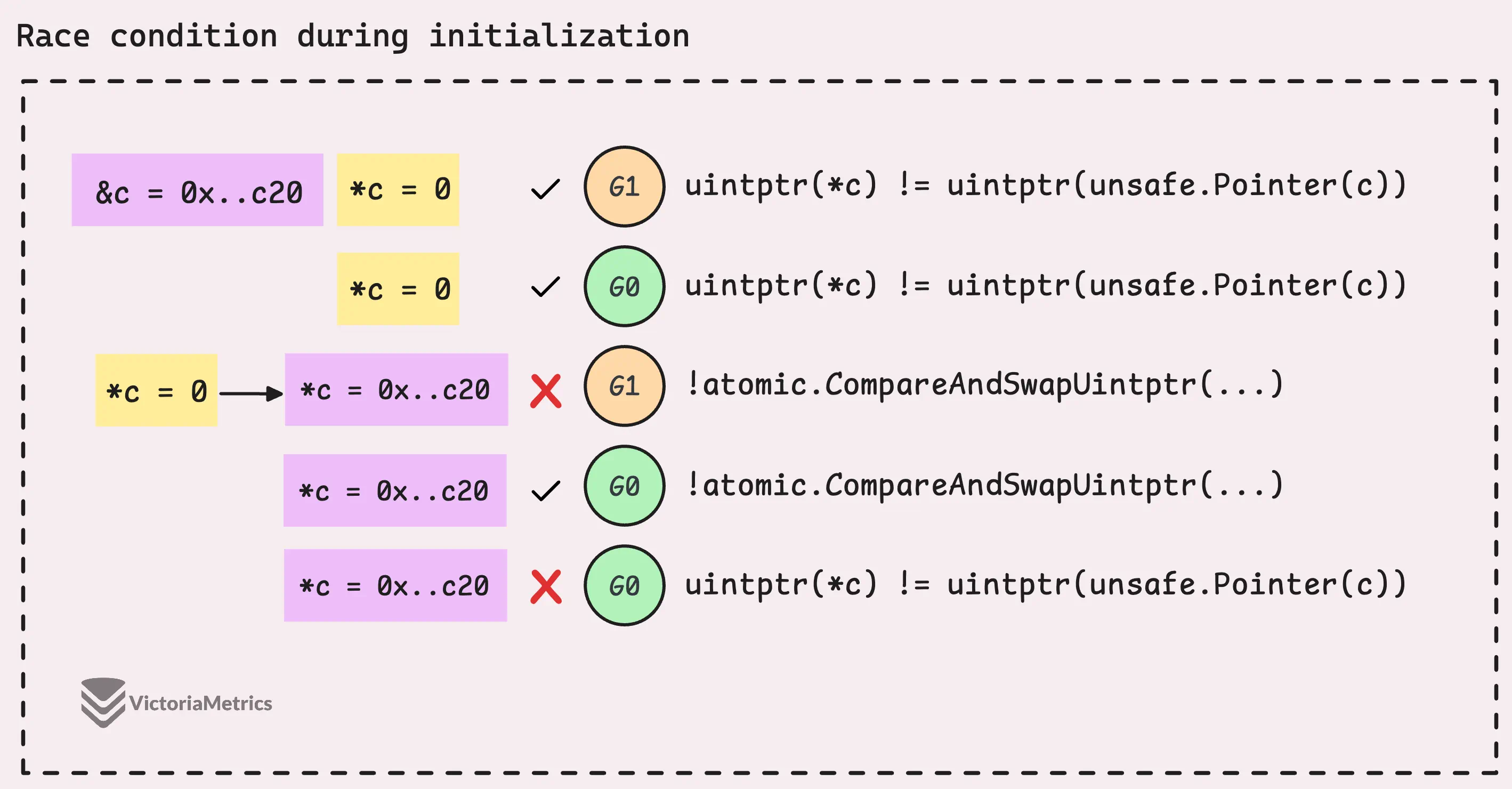

Let’s break this down into two main checks, since the first and last checks are doing pretty much the same thing.

The first check, uintptr(*c) != uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(c)), looks to see if the memory address has changed. If it has, the object’s been copied. But, there’s a catch, if this is the first time the copyChecker is being used, it’ll be 0 since it’s not initialized yet.

The second check, !atomic.CompareAndSwapUintptr((*uintptr)(c), 0, uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(c))), is where we use a Compare-And-Swap (CAS) operation to handle both initialization and checking:

- If CAS succeeds, it means the

copyCheckerwas just initialized, so the object hasn’t been copied yet, and we’re good to go. - If CAS fails, it means the

copyCheckerwas already initialized, and we need to do that final check (uintptr(*c) != uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(c))) to make sure the object hasn’t been copied.

The final check uintptr(*c) != uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(c)) (it’s the same as the first check) makes sure that the object hasn’t been copied after all that.

“Why the extra check at the end? Isn’t two checks enough to panic?”

The reason for the third check is that the first and second checks aren’t atomic.

If this is the first time the copyChecker is being used, it hasn’t been initialized yet, and its value will be zero. In that case, the check will pass incorrectly, even though the object hasn’t been copied but just hasn’t been initialized.

notifyList - Tick-based Notification List

#

Beyond the locking and copy-checking mechanisms, one of the other important parts of sync.Cond is the notifyList.

type Cond struct {

noCopy noCopy

L Locker

notify notifyList

checker copyChecker

}

type notifyList struct {

wait uint32

notify uint32

lock uintptr

head unsafe.Pointer

tail unsafe.Pointer

}

Now, the notifyList in the sync package and the one in the runtime package are different but share the same name and memory layout (in purpose). To really understand how it works, we’ll need to look at the version in the runtime package:

type notifyList struct {

wait atomic.Uint32

notify uint32

lock mutex

head *sudog

tail *sudog

}

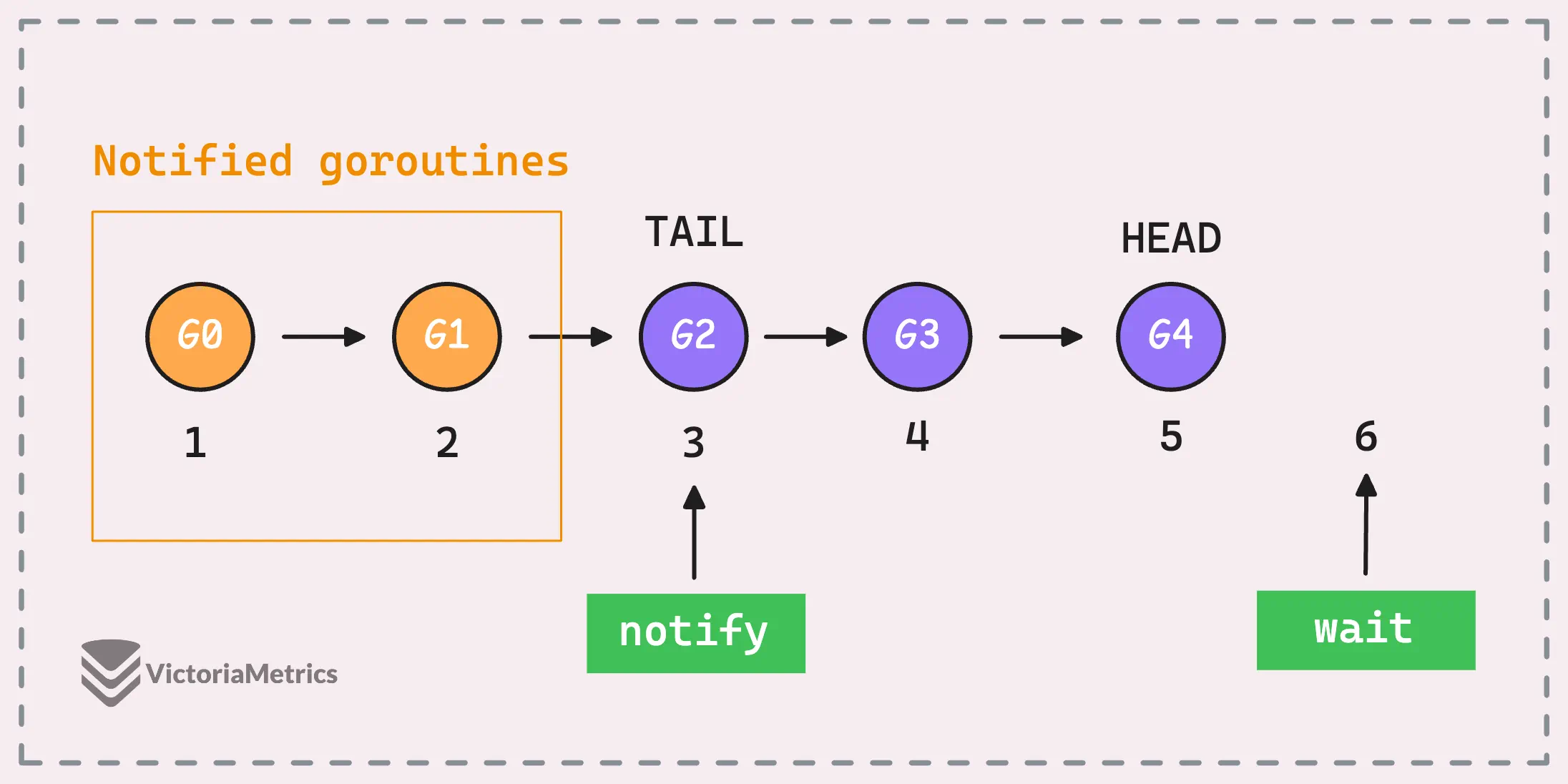

If you look at the head and tail, you probably guess this is some kind of linked list, and you’d be right. It’s a linked list of sudog (short for “pseudo-goroutine”), which represents a goroutine waiting on synchronization events, like waiting to receive or send data on a channel or waiting on a condition variable.

The head and tail are pointers to the first and last goroutine in this list. Meanwhile, the wait and notify fields act as “ticket” numbers that are continuously increasing, each representing a position in the queue of waiting goroutines.

wait: This number represents the next ticket that’s going to be issued to a waiting goroutine.notify: This tracks the next ticket number that’s supposed to be notified, or woken up.

And that’s the core idea behind notifyList, let’s put them together to see how it works.

notifyListAdd()

#

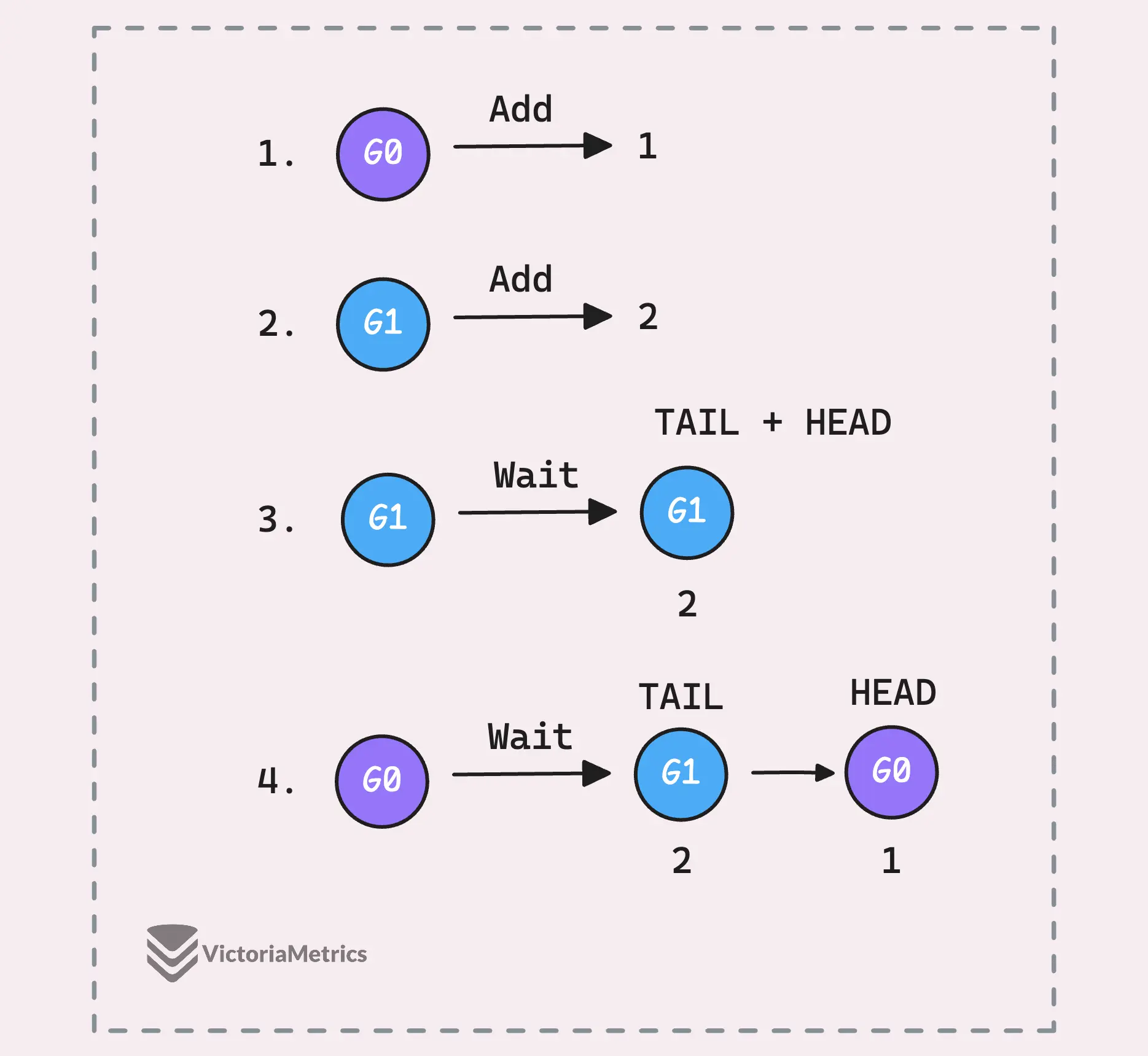

When a goroutine is about to wait for a notification, it calls notifyListAdd() to get its “ticket” first.

func (c *Cond) Wait() {

c.checker.check()

// Get the ticket number

t := runtime_notifyListAdd(&c.notify)

c.L.Unlock()

// Add the goroutine to the list and suspend it

runtime_notifyListWait(&c.notify, t)

c.L.Lock()

}

func notifyListAdd(l *notifyList) uint32 {

return l.wait.Add(1) - 1

}

The ticket assignment is handled by an atomic counter. So when a goroutine calls notifyListAdd(), that counter ticks up, and the goroutine is handed the next available ticket number.

Every goroutine gets its own unique ticket number, and this process happens without any lock. This means that multiple goroutines can request tickets at the same time without waiting for each other.

For example, if the current ticket counter is sitting at 5, the goroutine that calls notifyListAdd() next will get ticket number 5, and the wait counter will then bump up to 6, ready for the next one in line. The wait field always points to the next ticket number that’ll be issued.

But here’s where things get a little tricky.

Since many goroutines can grab a ticket at the same time, there’s a small gap between when they call notifyListAdd() and when they actually enter notifyListWait(). Their order isn’t necessarily guaranteed, even though the ticket numbers are issued sequentially, the order in which the goroutines get added to the linked list might not be 1, 2, 3. Instead, it could end up being 3, 2, 1, or 2, 1, 3, it all depends on the timing.

After getting its ticket, the next step for the goroutine is to “wait” for its turn to be notified. This happens when the goroutine calls notifyListWait(t), where t is the ticket number it just got.

func notifyListWait(l *notifyList, t uint32) {

lockWithRank(&l.lock, lockRankNotifyList)

// Return right away if this ticket has already been notified.

if less(t, l.notify) {

unlock(&l.lock)

return

}

// Enqueue itself.

s := acquireSudog()

...

if l.tail == nil {

l.head = s

} else {

l.tail.next = s

}

l.tail = s

goparkunlock(&l.lock, waitReasonSyncCondWait, traceBlockCondWait, 3)

...

releaseSudog(s)

}

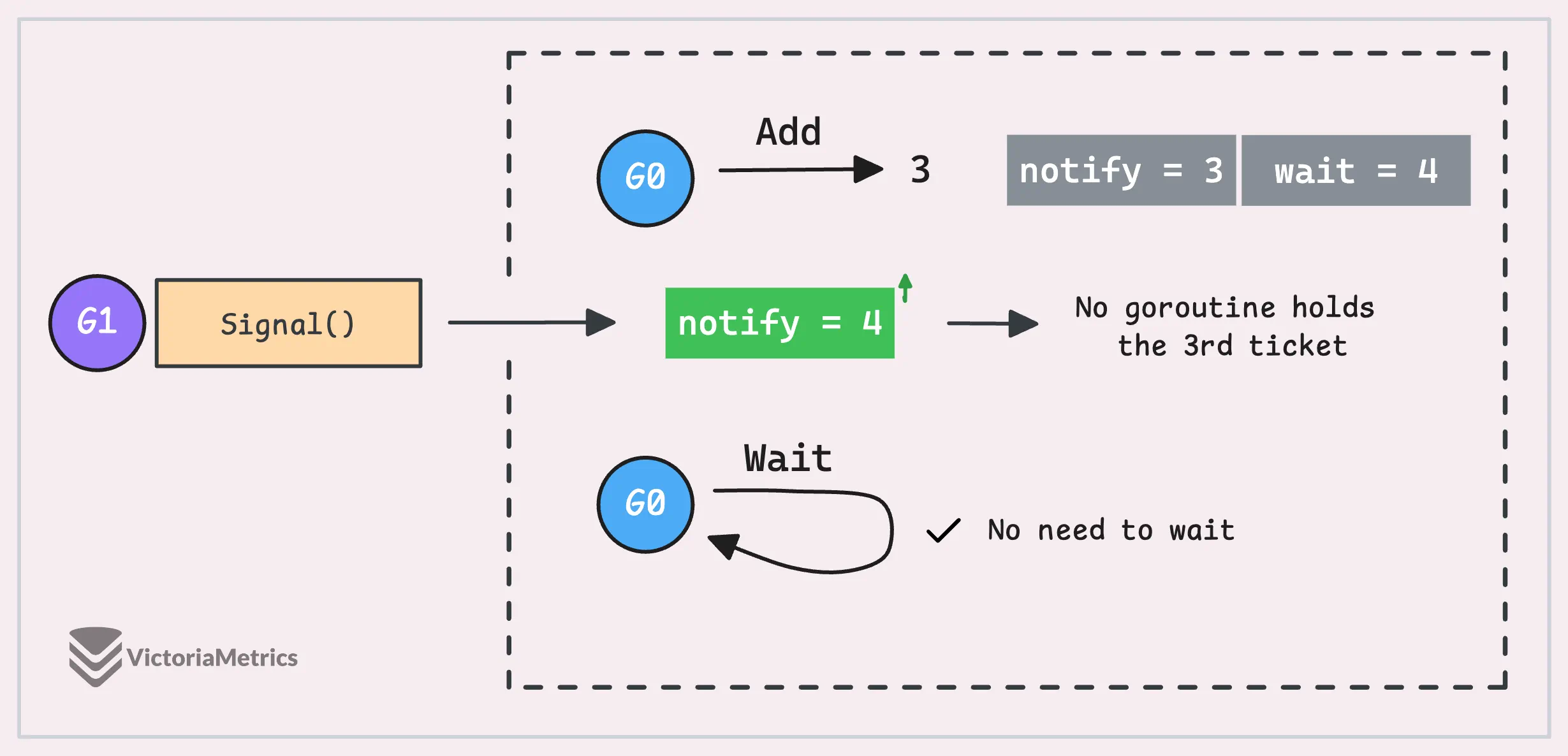

Before doing anything else, the goroutine checks if its ticket has already been notified.

It compares its own ticket (t) with the current notify number. If the notify number has already passed the goroutine’s ticket, it doesn’t have to wait at all—it can jump straight to the shared resource and get to work

It turns out, This quick check is really important, especially when we dive into how Signal() and Broadcast() work. But if the goroutine’s ticket hasn’t been notified yet, it adds itself to the waiting list and then goes to sleep, or “parks,” until being notified.

notifyListNotifyOne()

#

When it’s time to notify waiting goroutines, the system starts with the smallest ticket number that hasn’t been notified yet, this is tracked by l.notify.

func notifyListNotifyOne(l *notifyList) {

// Fast path: If there are no new waiters, do nothing.

if l.wait.Load() == atomic.Load(&l.notify) {

return

}

lockWithRank(&l.lock, lockRankNotifyList)

// Re-check under the lock to make sure there's something to do.

t := l.notify

if t == l.wait.Load() {

unlock(&l.lock)

return

}

// Move to the next ticket to notify.

atomic.Store(&l.notify, t+1)

// Find the goroutine with the matching ticket in the list.

for p, s := (*sudog)(nil), l.head; s != nil; p, s = s, s.next {

if s.ticket == t {

// Found the goroutine with the ticket.

n := s.next

if p != nil {

p.next = n

} else {

l.head = n

}

if n == nil {

l.tail = p

}

unlock(&l.lock)

s.next = nil

readyWithTime(s, 4) // Mark the goroutine as ready.

return

}

}

unlock(&l.lock)

}

Remember how we talked about the ticket order not being guaranteed?

You might have goroutines with tickets 2, 1, 3, but the notify number is always increasing sequentially. So, when the system is ready to wake up a goroutine, it loops through the linked list, looking for the goroutine holding the next ticket in line (the 1st). Once it finds it, it removes the goroutine from the list and marks it as ready to run.

But here’s where it gets interesting, there’s sometimes a timing issue. Let’s say a goroutine has grabbed a ticket, but it hasn’t yet been added to the list of waiting goroutines by the time this function runs.

What happens then? For example, the sequence could go like this: notifyListAdd() -> notifyListNotifyOne() -> notifyListWait().

In that case, the function scans through the list but doesn’t find a goroutine with the matching ticket. No worries, though, notifyListWait() takes care of this situation when the goroutine eventually calls it.

Remember that important check I mentioned earlier? The one in the notifyListWait() function: if less(t, l.notify) { ... }?

This check is important because it allows a goroutine holding a ticket number less than the current l.notify value to realize, “Hey, my turn’s already passed, I can go now.” In that case, the goroutine skips waiting and immediately proceeds to access the shared resource.

So, even if the goroutine hasn’t entered the linked list yet, it can still be notified if it’s holding a valid ticket. This is what makes the design so smooth, each goroutine can grab its ticket right away, without having to wait for others or for its turn to be added to the list. It keeps everything moving without unnecessary blocking.

notifyListNotifyAll()

#

Now, let’s talk about the last piece, Broadcast() or notifyListNotifyAll(). This one is a lot simpler compared to notifyListNotifyOne():

func notifyListNotifyAll(l *notifyList) {

// Fast path: If there are no new waiters, do nothing.

if l.wait.Load() == atomic.Load(&l.notify) {

return

}

lockWithRank(&l.lock, lockRankNotifyList)

s := l.head

l.head = nil

l.tail = nil

atomic.Store(&l.notify, l.wait.Load())

unlock(&l.lock)

// Ready all waiters in the list.

for s != nil {

next := s.next

s.next = nil

readyWithTime(s, 4)

s = next

}

}

The code is pretty simple, and I think you’ve got the gist already. Basically, Broadcast() goes through the entire list of waiting goroutines, marks all of them as ready, and clears out the list.

Let’s wrap up the article with a final warning: it’s very hard to get this right, very easy to misuse sync.Cond and bring in some tricky, hard-to-debug issues. After covering the technical side, I’d recommend checking out the proposal: sync: remove the Cond type as the next step from an engineering perspective.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Inside Go’s Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

- Go Sync.Once is Simple… Does It Really?

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus