New developers often think slices are pretty simple to get, just a dynamic array that can change size compared to a regular array. But honestly, it’s trickier than it seems when it comes to how they change size.

So, let’s say we have a slice variable a, and you assign it to another variable b. Now, both a and b are pointing to the same underlying array. If you make any changes to the slice a, you’re gonna see those changes reflected in b too.

But that’s not always the case.

The link between a and b isn’t all that strong, and in Go, you can’t count on every change in a showing up in b.

Experienced Go developers think of a slice as a pointer to an array, but here’s the catch: that pointer can change without notice, which makes slices tricky if you don’t fully understand how they work. In this discussion, we’ll cover everything from the basics to how slices grow and how they’re allocated in memory.

Before we get into the details, I’d suggest checking out how arrays work first.

How Slice is Structured

#

Once you declare an array with a specific length, that length is “locked” in as part of its type. For example, an array of [1024]byte is a completely different type from an array of [512]byte.

Now, slices are way more flexible than arrays since they’re basically a layer on top of an array. They can resize dynamically, and you can use append() to add more elements.

There are quite a few ways you can create a slice:

// a is a nil slice

var a []byte

// slice literal

b := []byte{1, 2, 3}

// slice from an array

c := b[1:3]

// slice with make

d := make([]byte, 1, 3)

// slice with new

e := *new([]byte)

That last one isn’t really common, but it’s legit syntax.

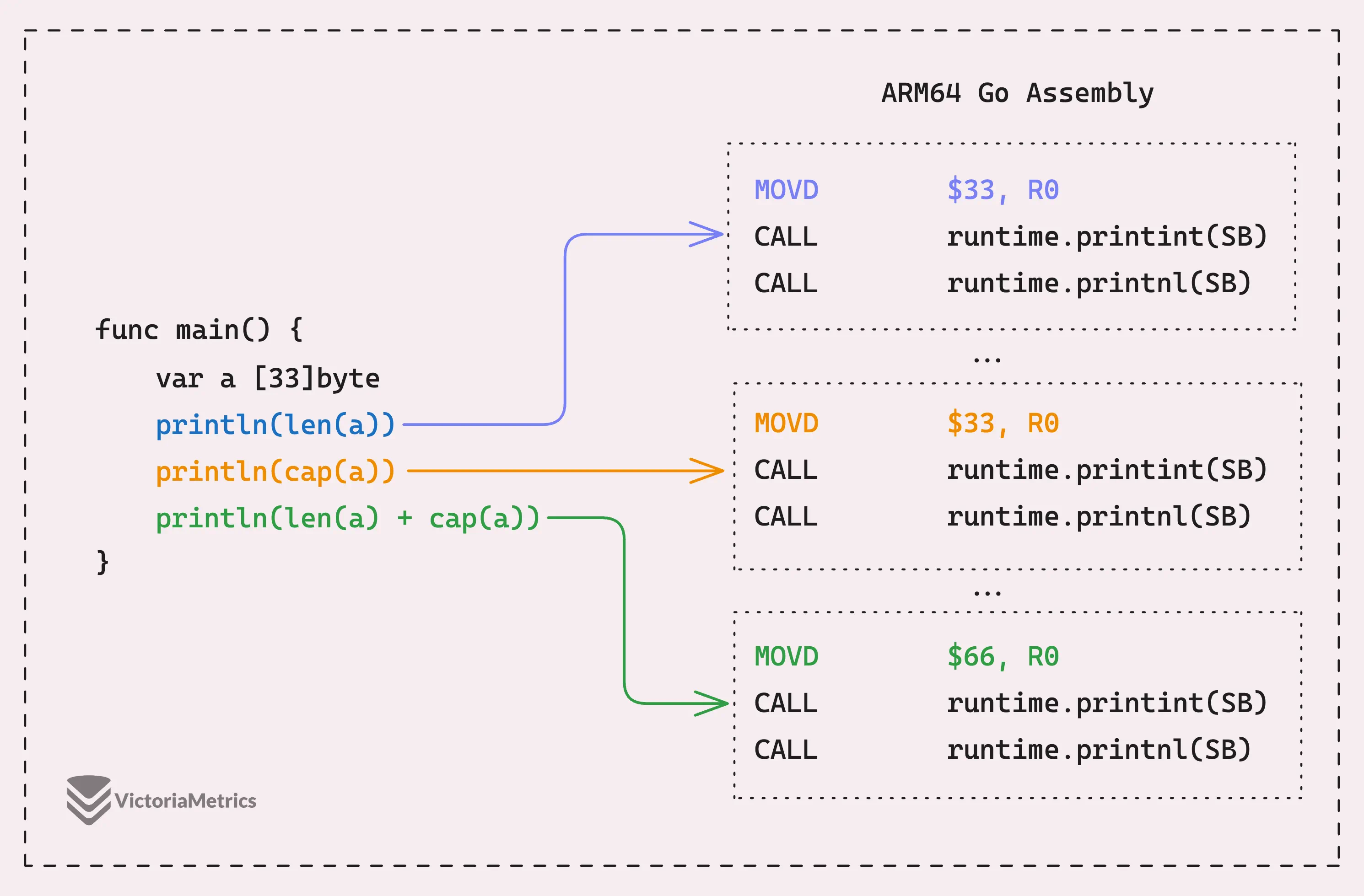

Unlike arrays, where len and cap are constants and always equal, slices are different. In arrays, the Go compiler knows the length and capacity ahead of time and even bakes that into the Go assembly code.

But with slices, len and cap are dynamic, meaning they can change at runtime.

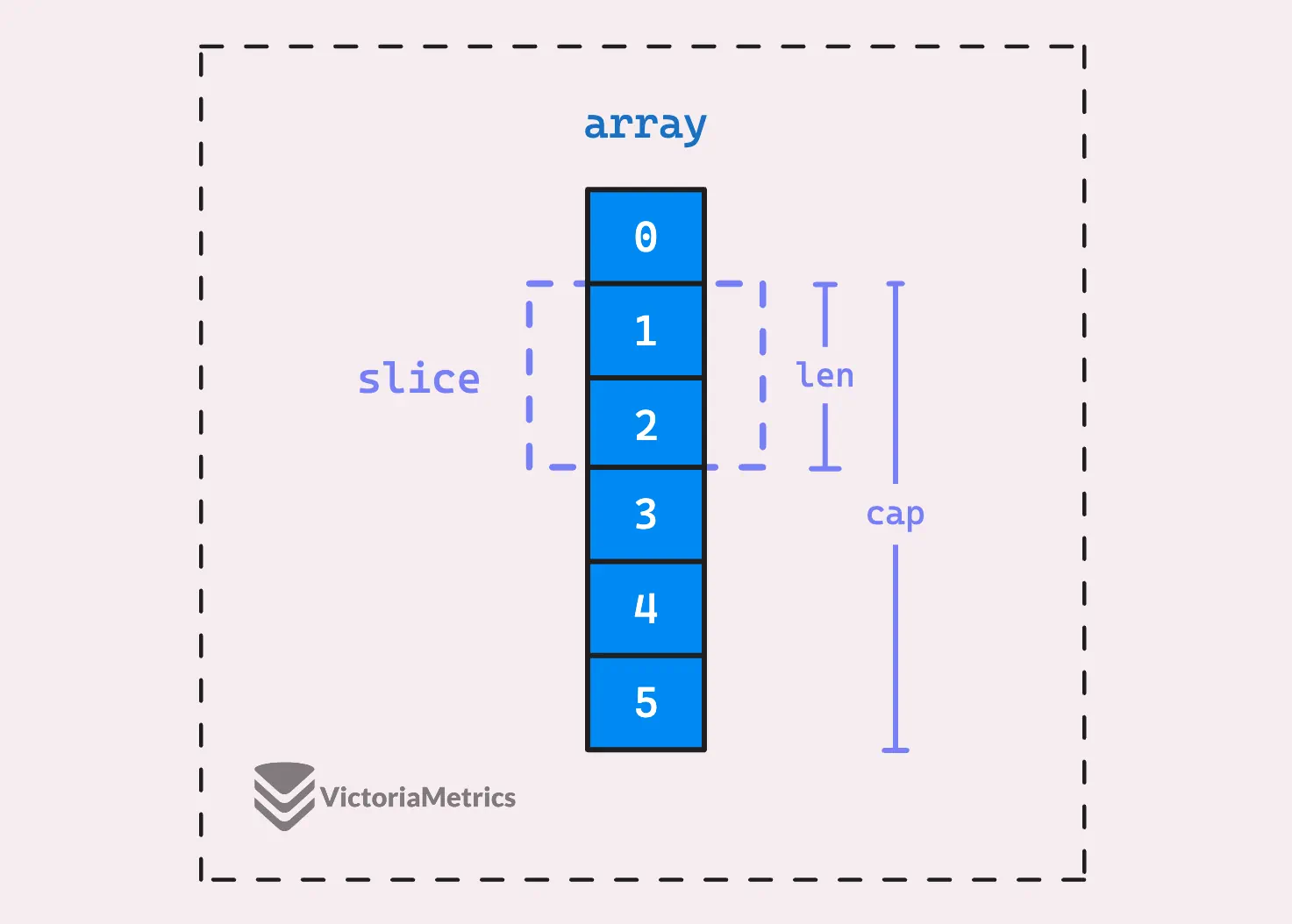

Slices are really just a way to describe a ‘slice’ of the underlying array.

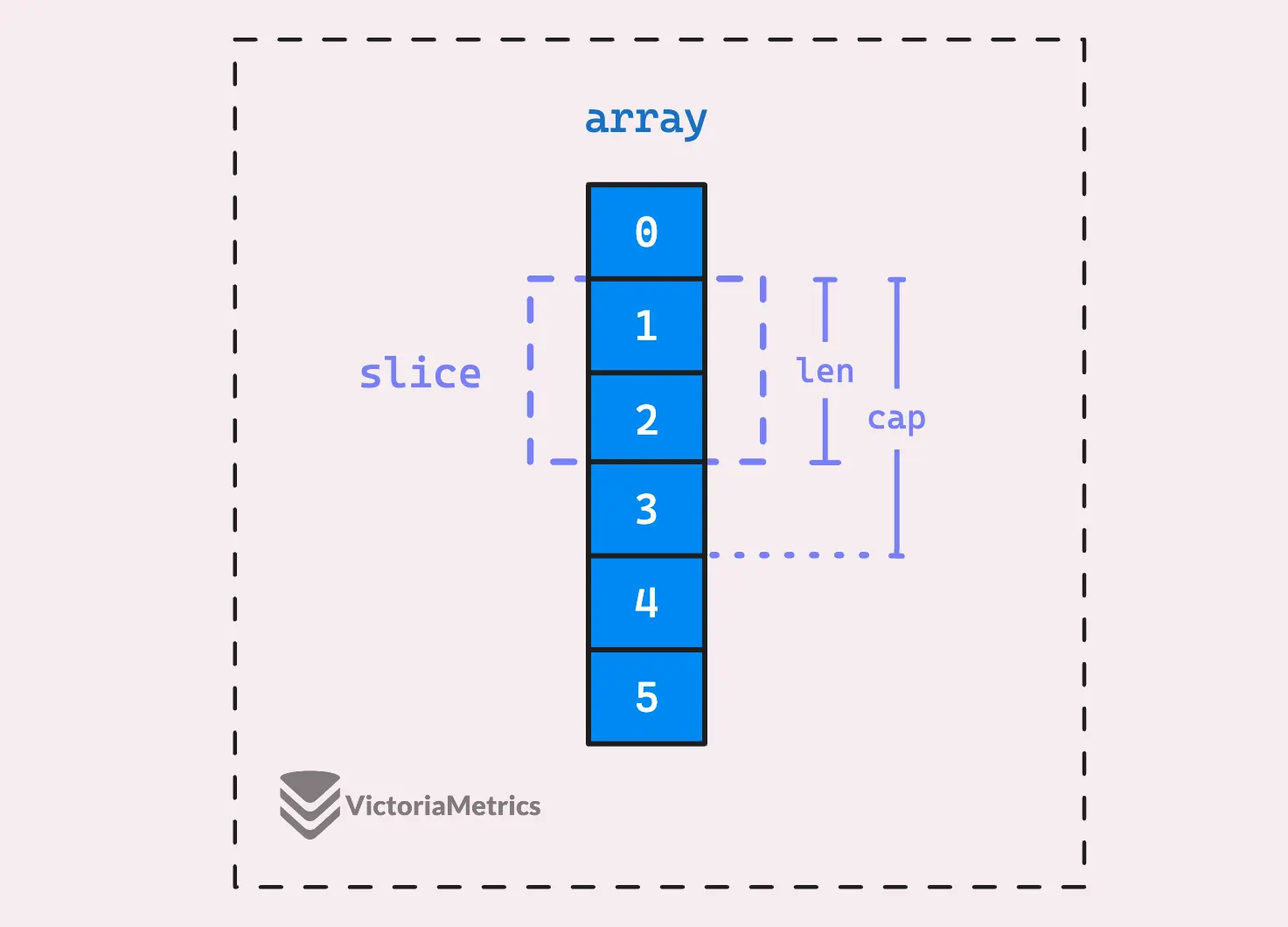

For example, if you have a slice like [1:3], it starts at index 1 and ends just before index 3, so the length is 3 - 1 = 2.

func main() {

array := [6]int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

slice := array[1:3]

fmt.Println(slice, len(slice), cap(slice))

}

// Output:

// [1 2] 2 5

The situation above could be represented as the following diagram.

The len of a slice is simply how many elements are in it. In this case, we have 2 elements [1, 2]. The cap is basically the number of elements from the start of the slice to the end of the underlying array.

That definition of capacity above is a bit inaccurate, we will talk about it in growing section.

Since a slice points to the underlying array, any changes you make to the slice will also change the underlying array.

“I know the length and capacity of a slice through the

lenandcapfunctions, but how do I figure out where the slice actually starts?”

Let me show you 3 ways to find the start of a slice by looking in its internal representation.

Instead of using fmt.Println, you can use println to get the raw values of the slice:

func main() {

array := [6]byte{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

slice := array[1:3]

println("array:", &array)

println("slice:", slice, len(slice), cap(slice))

}

// Output:

// array: 0x1400004e6f2

// slice: [2/5]0x1400004e6f3 2 5

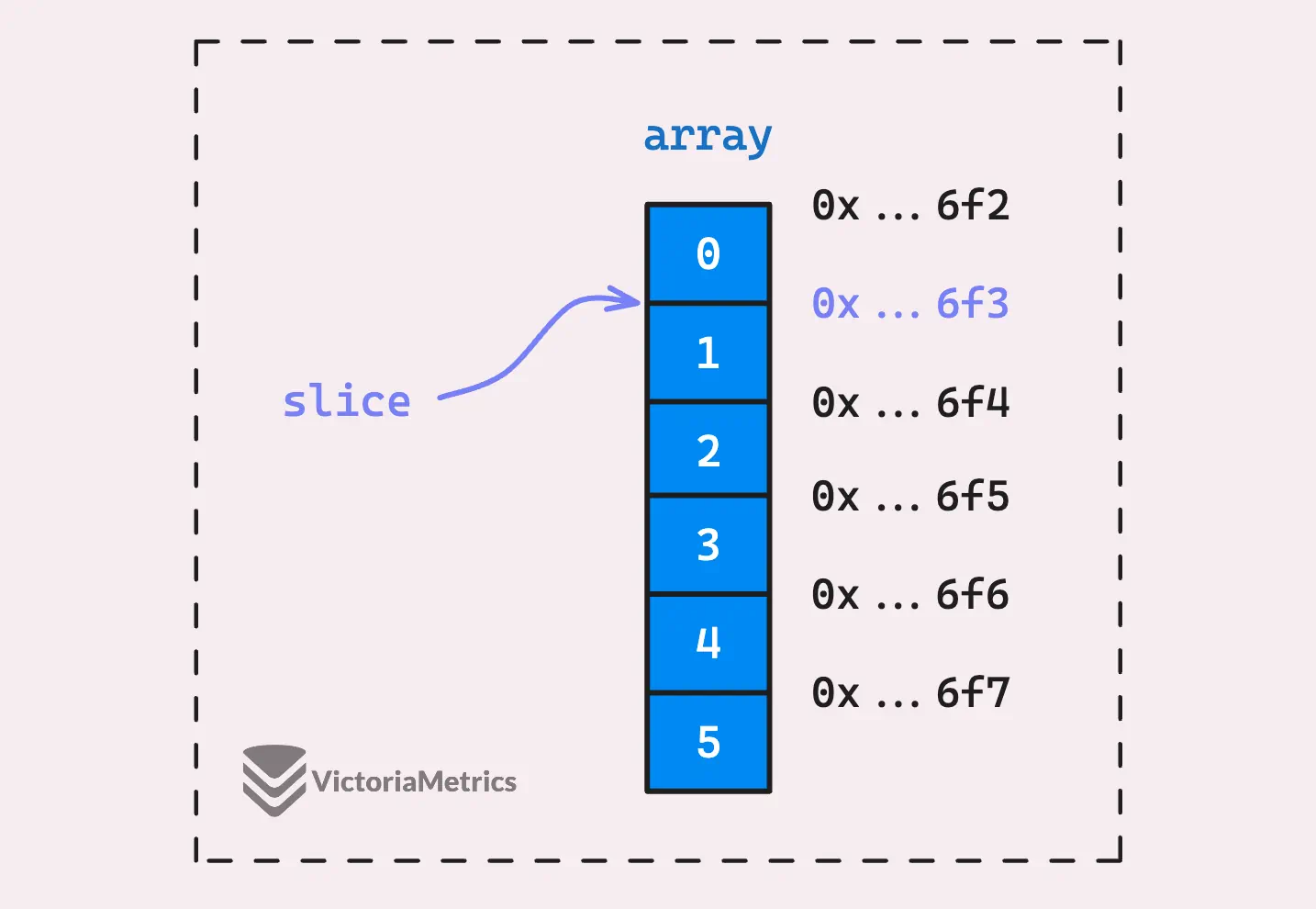

From that output, you can see that the address of the slice’s underlying array is different from the address of the original array, that’s weird, right?

Let’s visualize this in the diagram below.

If you’ve checked out the earlier post on arrays, you’ll get how elements are stored in an array. What’s really happening is that the slice is pointing directly to array[1].

The second way to prove it is by getting the pointer to the slice’s underlying array using unsafe.SliceData:

func main() {

array := [6]byte{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

slice := array[1:3]

arrPtr := unsafe.SliceData(slice)

println("array[1]:", &array[1])

println("slice.array:", arrPtr)

}

// Output:

// array[1]: 0x1400004e6f3

// slice.array: 0x1400004e6f3

When you pass a slice to unsafe.SliceData, it does a few checks to figure out what to return:

- If the slice has a capacity greater than 0, the function returns a pointer to the first element of the slice (which is

array[1]in this case). - If the slice is nil, the function just returns nil.

- If the slice isn’t nil but has zero capacity (an empty slice), the function gives you a pointer, but it’s pointing to “unspecified memory address”.

You can find all of this documented in the Go documentation.

“What do you mean by ‘This pointer is pointing to an unspecified memory address’?”

It’s a bit out of context, but let’s satisfy our curiosity :)

In Go, you can have types with zero size, like struct{} or [0]int. When the Go runtime allocates memory for these types, instead of giving each one a unique memory address, it just returns the address of a special variable called zerobase.

You’re probably getting the idea, right?

The ‘unspecified’ memory we mentioned earlier is this zerobase address.

func main() {

var a struct{}

fmt.Printf("struct{}: %p\n", &a)

var b [0]int

fmt.Printf("[0]int: %p\n", &b)

fmt.Println("unsafe.SliceData([]int{}):", unsafe.SliceData([]int{}))

}

// Output:

// struct{}: 0x104f24900

// [0]int: 0x104f24900

// unsafe.SliceData([]int{}): 0x104f24900

Pretty cool, right? It’s like we just uncovered a little mystery that Go was keeping under wraps.

Let’s move on to the third way.

Behind the scenes, a slice is just a struct with three fields: array—a pointer to the underlying array, len—the length of the slice, and cap—the capacity of the slice.

type slice struct {

array unsafe.Pointer

len int

cap int

}

This is also the setup for our third way to figure out the start of a slice. While we’re at it, we’ll prove that the struct above is indeed how slices work internally.

type sliceHeader struct {

array unsafe.Pointer

len int

cap int

}

func main() {

array := [6]byte{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

slice := array[1:3]

println("slice", slice)

header := (*sliceHeader)(unsafe.Pointer(&slice))

println("sliceHeader:", header.array, header.len, header.cap)

}

// Output:

// slice [2/5]0x1400004e6f3

// sliceHeader: 0x1400004e6f3 2 5

The output is exactly what we expect and we usually refer to this internal structure as the slice header (sliceHeader). There’s also a reflect.SliceHeader in the reflect package, but that’s deprecated.

Now that we’ve mastered how slices are structured, it’s time to dive into how they actually behave.

How Slice Grows

#

Earlier, I mentioned that “the cap is basically the length of the underlying array starting from the first element of the slice up to the end of that array.” That’s not entirely accurate, it’s only true in that specific example.

For instance, when you create a new slice using slicing operations, there’s an option to specify the capacity of the slice:

func main() {

array := [6]int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

slice := array[1:3:4]

println(slice)

}

// Output:

// [2/3]0x1400004e718

By default, if you don’t specify the third parameter in the slicing operation, the capacity is taken from the sliced slice or the length of the sliced array.

In this example, the capacity of slice is set to go up to index 4 (exclusive, like the length) of the original array.

So, let’s redefine what the capacity of a slice really means.

“The capacity of a slice is the maximum number of elements it can hold before it needs to grow.”

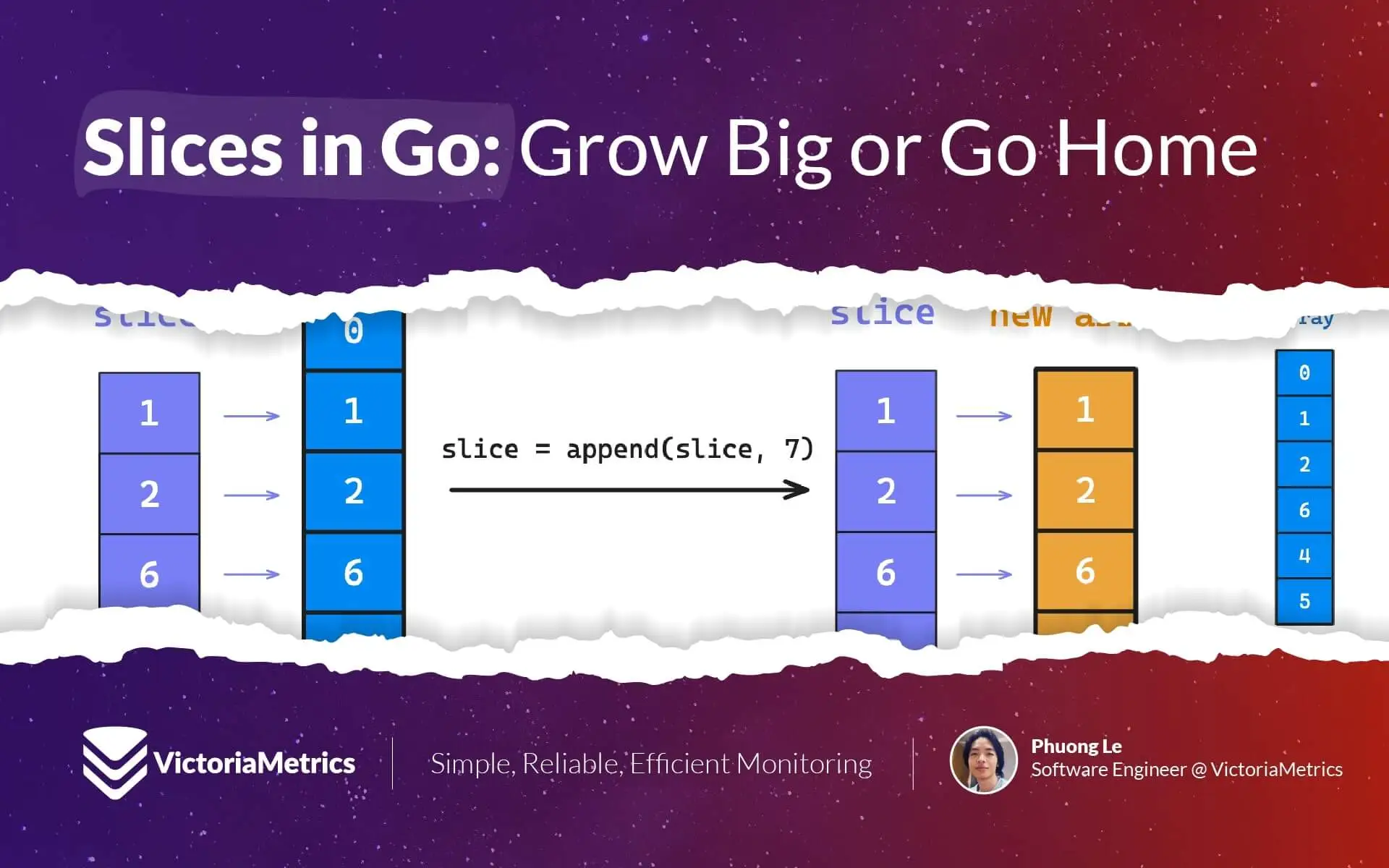

If you keep adding elements to a slice and it surpasses its current capacity, Go will automatically create a larger array, copy the elements over, and use that new array as the slice’s underlying array.

Let’s see how this works in practice.

func main() {

array := [6]int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

slice := array[1:3:4]

fmt.Println("slice:", slice)

slice = append(slice, 6)

fmt.Println("slice after appending 6:", slice, unsafe.SliceData(slice))

fmt.Println("array now:", array)

slice = append(slice, 7)

fmt.Println("slice after appending 7:", slice, unsafe.SliceData(slice))

fmt.Println("array now:", array)

}

// Output:

// slice: [1 2]

// slice after appending 6: [1 2 6] 0x14000128038

// array now: [0 1 2 6 4 5]

// slice after append 7: [1 2 6 7] 0x14000128090

// array now: [0 1 2 6 4 5]

So, what’s happening here?

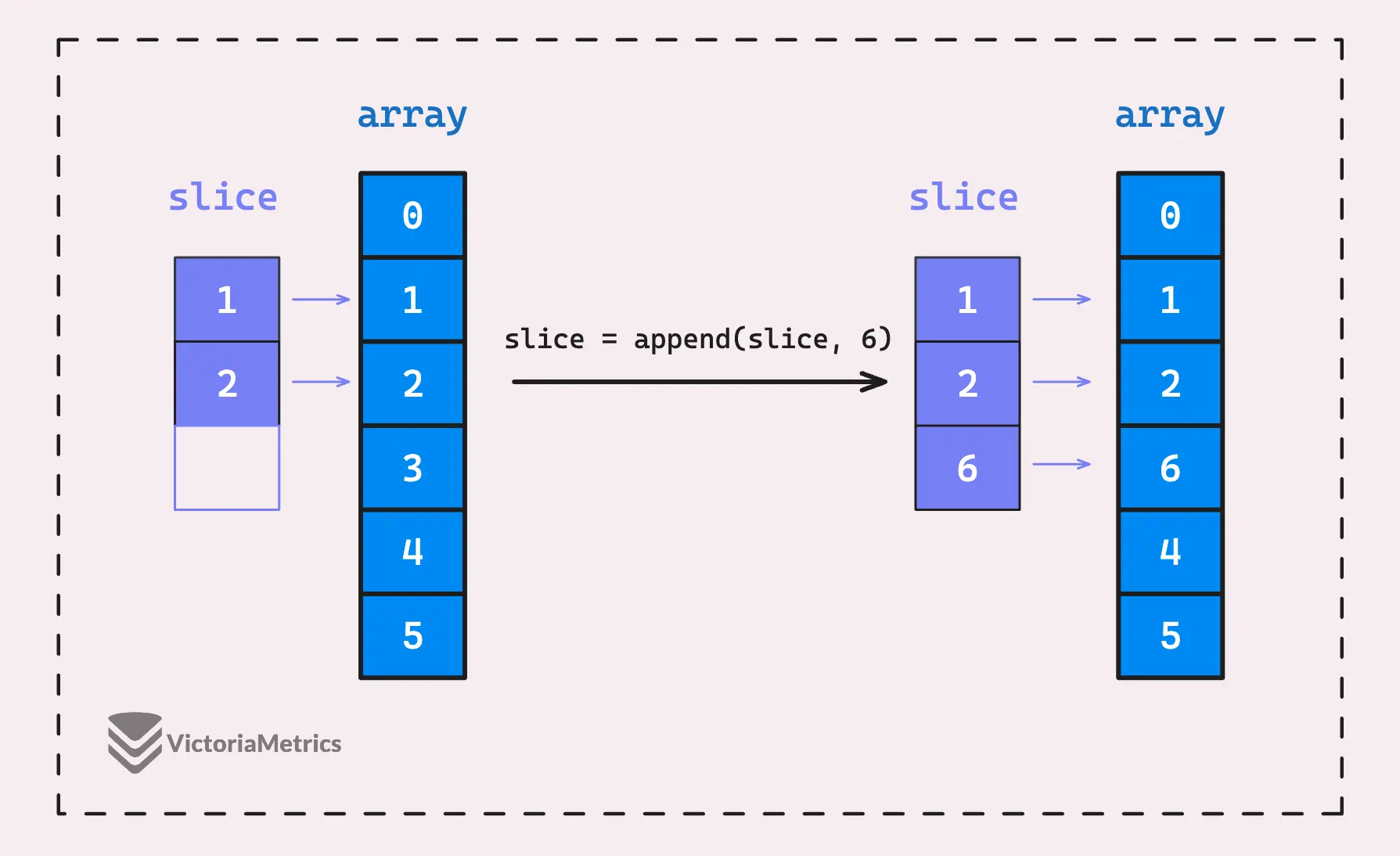

When we append 6 to the slice [1 2], the slice is still pointing to the underlying array [0 1 2 3 4 5]. The way append() works in this case is similar to array[2] = 6, directly setting the element at index 2 of the underlying array to 6.

So now the array becomes [0 1 2 6 4 5], and our slice is [1 2 6].

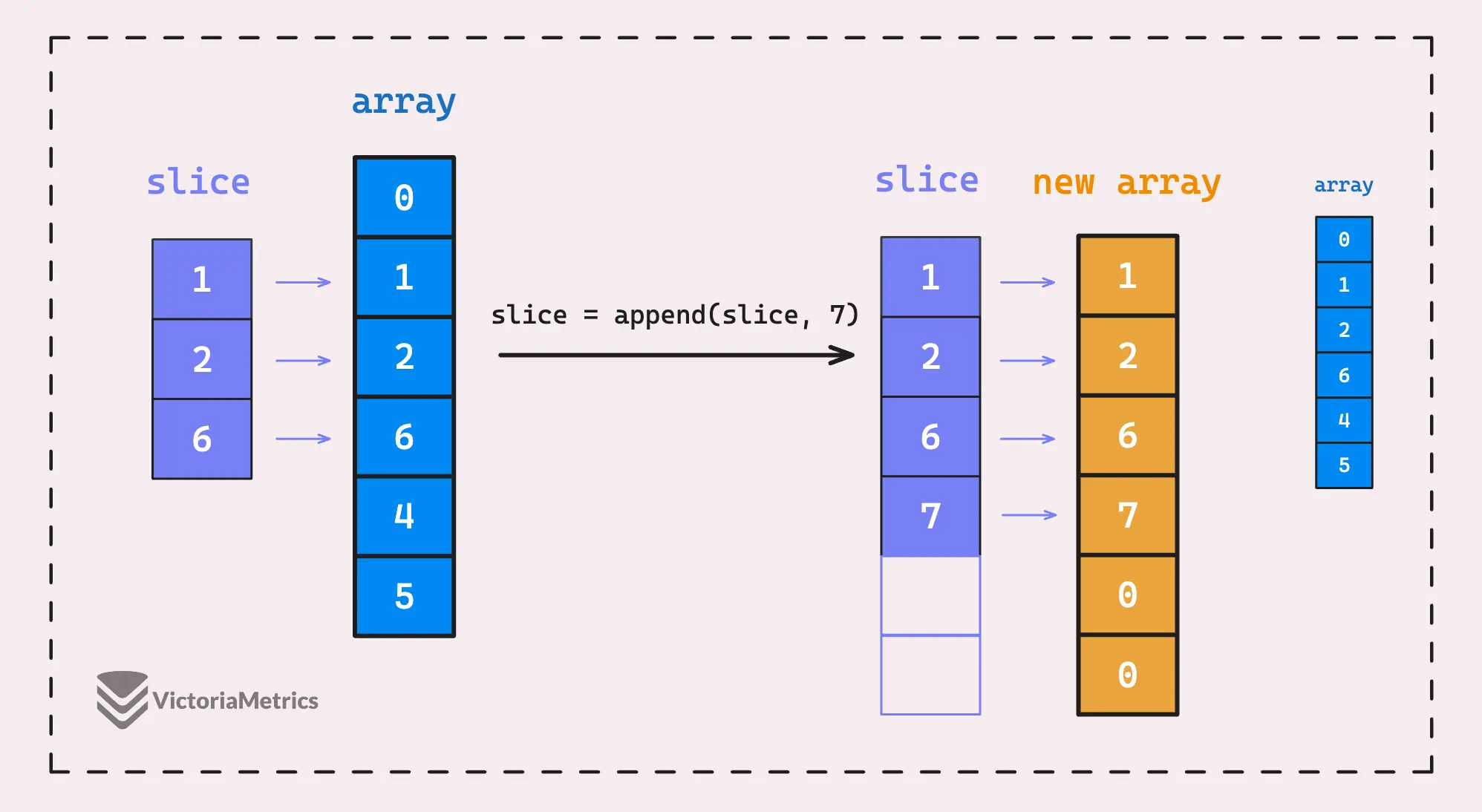

But when we append 7 to the slice, the slice exceeds its own capacity (not the array’s capacity), so Go creates a new underlying array, copies the elements over, and then appends 7 to this new slice.

The new array has an address of 0x14000128090, which is different from the old one 0x14000128038.

This is also a common mistake new developers make when two slices that used to share the same data no longer do after an append() operation. The most typical scenario is when a slice is passed as a function argument:

func changeSlice(slice []int) {

slice[0] = 100

slice = append(slice, 400, 500)

}

func main() {

slice := []int{1, 2, 3}

changeSlice(slice)

fmt.Println(slice)

}

// Output: [100 2 3]

In this example, the original slice is indeed modified, but only to [100 2 3], not [100 2 3 400 500].

“What about the capacity of the new slice?”

When Go creates a new array to adapt a growing slice, it usually doubles the capacity, but this changes once the slice reaches a certain size.

Here’s a quick look at how capacity grows from 0:

| Capacity | []int8 | []int32 | []int64 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| 256 | 256 | 256 | 256 |

| 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 |

| 848 | 848 | ||

| 864 | 864 | ||

| 896 | 896 | ||

| 1280 | 1280 | ||

| 1344 | 1344 | ||

| 1408 | 1408 | ||

| 1792 | 1792 | ||

| 2048 | 2048 | 2048 | |

| 2560 | 2560 | ||

| 3072 | 3072 | 3072 | 3072 |

| 3408 | 3408 | ||

| 4096 | 4096 | 4096 | 4096 |

| 5120 | 5120 | ||

| 5376 | 5376 | ||

| 5440 | 5440 | ||

| 6912 | 6912 | ||

| 7168 | 7168 | 7168 | |

| 9216 | 9216 | ||

| 9472 | 9472 | ||

| 10240 | 10240 | 10240 | |

| 12288 | 12288 | 12288 |

When the slice is small, the capacity doubling allows for fast growth.

But doubling capacity indefinitely would lead to huge memory allocations as the slice gets larger. To avoid that, Go adjusts the growth rate once the slice reaches a certain size, typically around 256.

At this point, the growth slows down, following this formula:

oldCap + (oldCap + 3*256) / 4

With some basic math, you can see that it equates to 1.25 * oldCap + 192. This keeps the slice growing efficiently without wasting too much memory.

But keep in mind, this value is just a hint, an approximation.

The table above tells a different story depending on the type of slice, and that’s because Go has to consider other factors like alignment, page size, size classes, and so on, all of which relate to how memory is allocated using certain predefined sizes.

Oh, one final trick before we move on.

If you need to increase the length of an existing slice in Go, you don’t always have to use the append() function or create a new slice. You can simply extend the slice using a slicing operation by specifying a length that’s greater than the current length.

func main() {

array := [6]int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

slice := array[1:3] // [1 2]

slice = slice[:len(slice)+1] // [1 2 3]

}

This method works as long as the new length does not exceed the slice’s capacity.

How Slice Is Allocated

#

Typically, anything dynamic or with an unknown size in a function ends up on the heap.

So, you’d think slices would always be allocated on the heap too, right?

Actually, no. It’s a mistake to assume that slices are always heap-allocated. We need to consider two things separately: the slice itself (which is just the slice header) and the underlying array.

1. The first case: both the slice and its underlying array are allocated on the stack.

func doSomething() {

a := byte(1)

println("a's address:", &a)

s := make([]byte, 1)

println("slice's address:", &s)

println("underlying array's address:", s)

}

// Output:

// a's address: 0x1400004e71e

// slice's address: 0x1400004e720

// underlying array's address: [1/1]0x1400004e71f

Escape analysis tells us: “make([]int, 1) does not escape”.

And as you can see from the output, the local variable a, the slice s, and the underlying array s.array are all allocated on the stack, their addresses are close to each other.

The slice itself is pretty straightforward, right?

It’s just a simple struct with 3 fields, so it’s usually allocated on the stack unless you do something that causes the slice itself to outlive the function.

The underlying array, on the other hand, is more likely to end up on the heap because it’s created on the fly, either when you allocate a slice with a certain number of elements or when the slice grows and needs more space.

“But why is the underlying array in the example above allocated on the stack?”

The size of the underlying array is known at compile time, so Go can optimize the allocation and place it on the stack.

But let’s take a look at another example.

2. The second case: the underlying array starts on the stack, then grows to the heap.

func main() {

slice := make([]int, 0, 3)

println("slice:", slice, "- slice addr:", &slice)

slice = append(slice, 1, 2, 3)

println("slice full cap:", slice)

slice = append(slice, 4)

println("slice after exceed cap:", slice)

}

// Output:

// slice: [0/3]0x1400004e720 - slice addr: 0x1400004e738

// slice full cap: [3/3]0x1400004e720

// slice after exceed cap: [4/6]0x14000016210

Notice how the address of the underlying array changes dramatically when the slice exceeds its capacity, from 0x1400004e720 to 0x14000016210.

At this point, it’s no longer on our goroutine stack.

This is why setting a predefined capacity is a good idea to avoid unnecessary heap allocation. Even if you don’t know the exact size at compile time, giving the slice an estimated capacity is better than leaving it at zero.

People often assume that growing a slice is fast and no big deal.

But if it’s in a hot path, it can definitely add overhead (allocate new memory, move data around, etc.), not just for the runtime but also for the garbage collector.

3. The third case: the underlying array is allocated on the heap.

Even if you predefine a capacity that’s known at compile time, there are still situations where the underlying array ends up on the heap.

One of these situations happens when using the make() function, if the capacity exceeds 64 KB:

func main() {

sliceA := make([]byte, 64 * 1024)

println("sliceA address:", &sliceA)

println("sliceA:", sliceA)

sliceB := make([]byte, 64 * 1024 + 1)

println("sliceB address:", &sliceB)

println("sliceB:", sliceB)

}

// Output:

// sliceA address: 0x1400019ff30

// sliceA: [65536/65536]0x1400018ff18

// sliceB address: 0x1400019ff18

// sliceB: [65537/65537]0x14000102000

Here, the underlying array of sliceA is allocated on the stack, exactly 64 KB away from the sliceA address. But with sliceB, the underlying array is allocated on the heap.

Let’s see what the escape analysis says in this case:

make([]byte, 65536) does not escape

make([]byte, 65537) escapes to heap

This tells us that the underlying array of sliceB is allocated on the heap, but not the slice header itself. How do we know? If the slice header variable sliceB had moved to the heap, the escape analysis would have mentioned something like: “moved to heap: sliceB.”

And it’s pretty easy to force the underlying array to be allocated on the heap, anything dynamic at compile time will end up there.

func arrayOnHeap(n int) {

slice := make([]int, n)

println("slice:", slice, "- slice addr:", &slice)

}

Because the stack size is determined at compile time, the underlying array of slice will definitely be on the heap as its size is n, which is determined at runtime.

So, what should we do to avoid heap allocation in these cases?

In most situations, it’s tough to estimate the size of a slice at compile time, so you can’t entirely avoid heap allocation the first time.

However, you can use make() with a capacity that’s known at runtime to reduce the chances of additional heap allocations later on.

Using sync.Pool is a good option, as we can reuse the underlying array of the slice for the same purpose and expect that the task will have the same size. Before putting the slice back in the pool, set the length of the slice to 0 (slice = slice[:0]), so next time you can use append() naturally.

There is an article: Go sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It that you might be interested in.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- Go Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Go Sync Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Inside Go’s Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What Is It?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.