This post is part of a series about handling concurrency in Go:

- Go sync.Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- Go sync.WaitGroup and The Alignment Problem

- Go sync.Pool and the Mechanics Behind It

- Go sync.Cond, the Most Overlooked Sync Mechanism

- Go sync.Map: The Right Tool for the Right Job

- Go Sync.Once is Simple… Does It Really?

- Go Singleflight Melts in Your Code, Not in Your DB (We’re here)

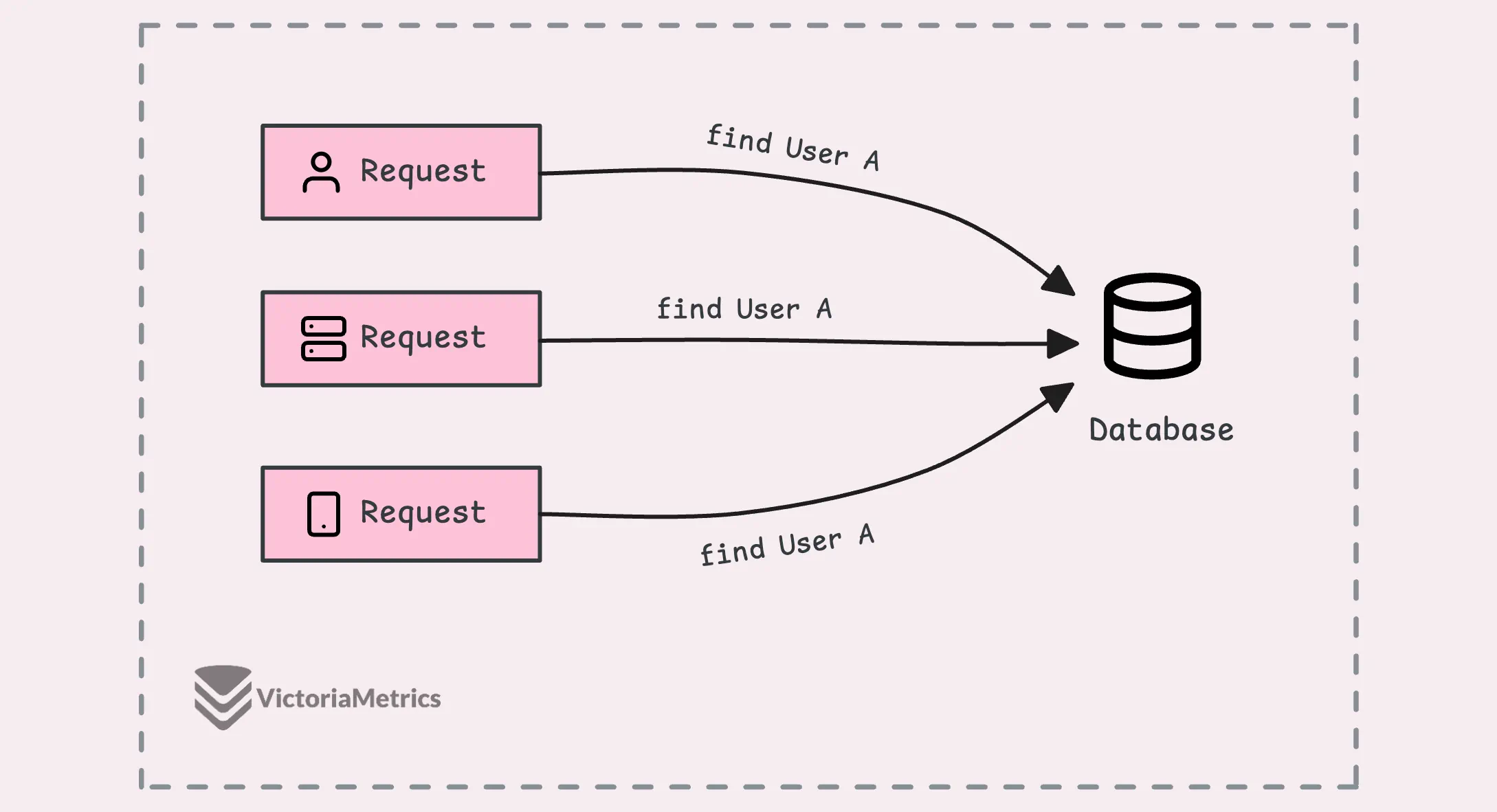

So, when you’ve got multiple requests coming in at the same time asking for the same data, the default behavior is that each of those requests would go to the database individually to get the same information. What that means is that you’d end up executing the same query several times, which, let’s be honest, is just inefficient.

It ends up putting unnecessary load on your database, which could slow everything down, but there’s a way around this.

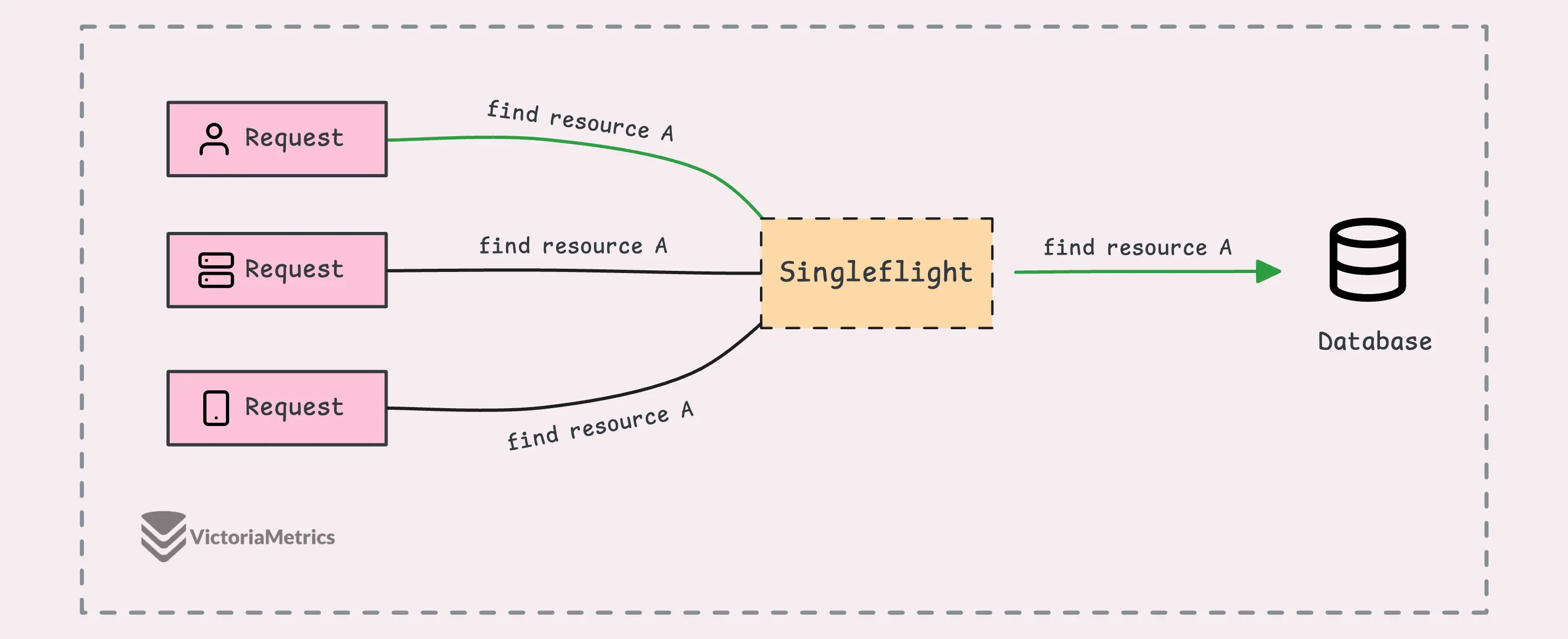

The idea is that only the first request actually goes to the database. The rest of the requests wait for that first one to finish. Once the data comes back from the initial request, the other ones just get the same result—no extra queries needed.

So, now you’ve got a pretty good idea of what this post is about, right?

Singleflight

#

The singleflight package in Go is built specifically to handle exactly what we just talked about. And just a heads-up, it’s not part of the standard library but it’s maintained and developed by the Go team.

What singleflight does is ensure that only one of those goroutines actually runs the operation, like getting the data from the database. It allows only one “in-flight” (ongoing) operation for the same piece of data (known as a “key”) at any given moment.

So, if other goroutines ask for the same data (same key) while that operation is still going, they’ll just wait. Then, when the first one finishes, all the others get the same result without having to run the operation again.

Alright, enough talk, let’s dive into a quick demo to see how singleflight works in action:

var callCount atomic.Int32

var wg sync.WaitGroup

// Simulate a function that fetches data from a database

func fetchData() (interface{}, error) {

callCount.Add(1)

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

return rand.Intn(100), nil

}

// Wrap the fetchData function with singleflight

func fetchDataWrapper(g *singleflight.Group, id int) error {

defer wg.Done()

time.Sleep(time.Duration(id) * 40 * time.Millisecond)

v, err, shared := g.Do("key-fetch-data", fetchData)

if err != nil {

return err

}

fmt.Printf("Goroutine %d: result: %v, shared: %v\n", id, v, shared)

return nil

}

func main() {

var g singleflight.Group

// 5 goroutines to fetch the same data

const numGoroutines = 5

wg.Add(numGoroutines)

for i := 0; i < numGoroutines; i++ {

go fetchDataWrapper(&g, i)

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("Function was called %d times\n", callCount.Load())

}

// Output:

// Goroutine 0: result: 90, shared: true

// Goroutine 2: result: 90, shared: true

// Goroutine 1: result: 90, shared: true

// Goroutine 3: result: 13, shared: true

// Goroutine 4: result: 13, shared: true

// Function was called 2 times

What’s going on here:

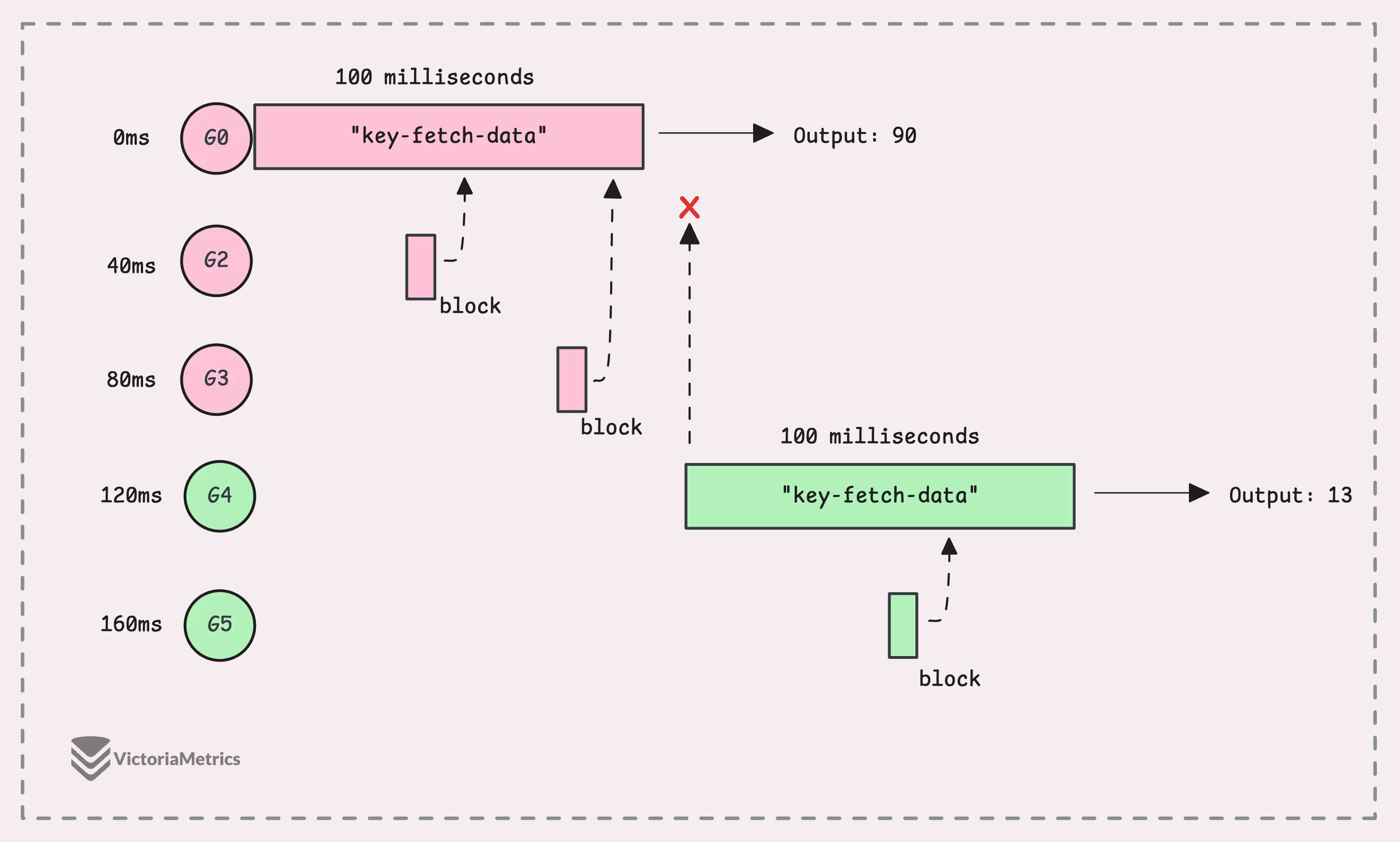

We’re simulating a situation where 5 goroutines try to fetch the same data almost at the same time, spaced 60ms apart. To keep it simple, we’re using random numbers to mimic data fetched from a database.

With singleflight.Group, we make sure only the first goroutine actually runs fetchData() and the rest of them wait for the result.

The line v, err, shared := g.Do("key-fetch-data", fetchData) assigns a unique key (“key-fetch-data”) to track these requests. So, if another goroutine asks for the same key while the first one is still fetching the data, it waits for the result rather than starting a new call.

Once the first call finishes, any waiting goroutines get the same result, as we can see in the output. Although we had 5 goroutines asking for the data, fetchData only ran twice, which is a massive boost.

The shared flag confirms that the result was reused across multiple goroutines.

“But why is the

sharedflag true for the first goroutine? I thought only the waiting ones would haveshared == true?”

Yeah, this might feel a bit counterintuitive if you’re thinking only the waiting goroutines should have shared == true.

The thing is, the shared variable in g.Do tells you whether the result was shared among multiple callers. It’s basically saying, “Hey, this result was used by more than one caller.” It’s not about who ran the function, it’s just a signal that the result was reused across multiple goroutines.

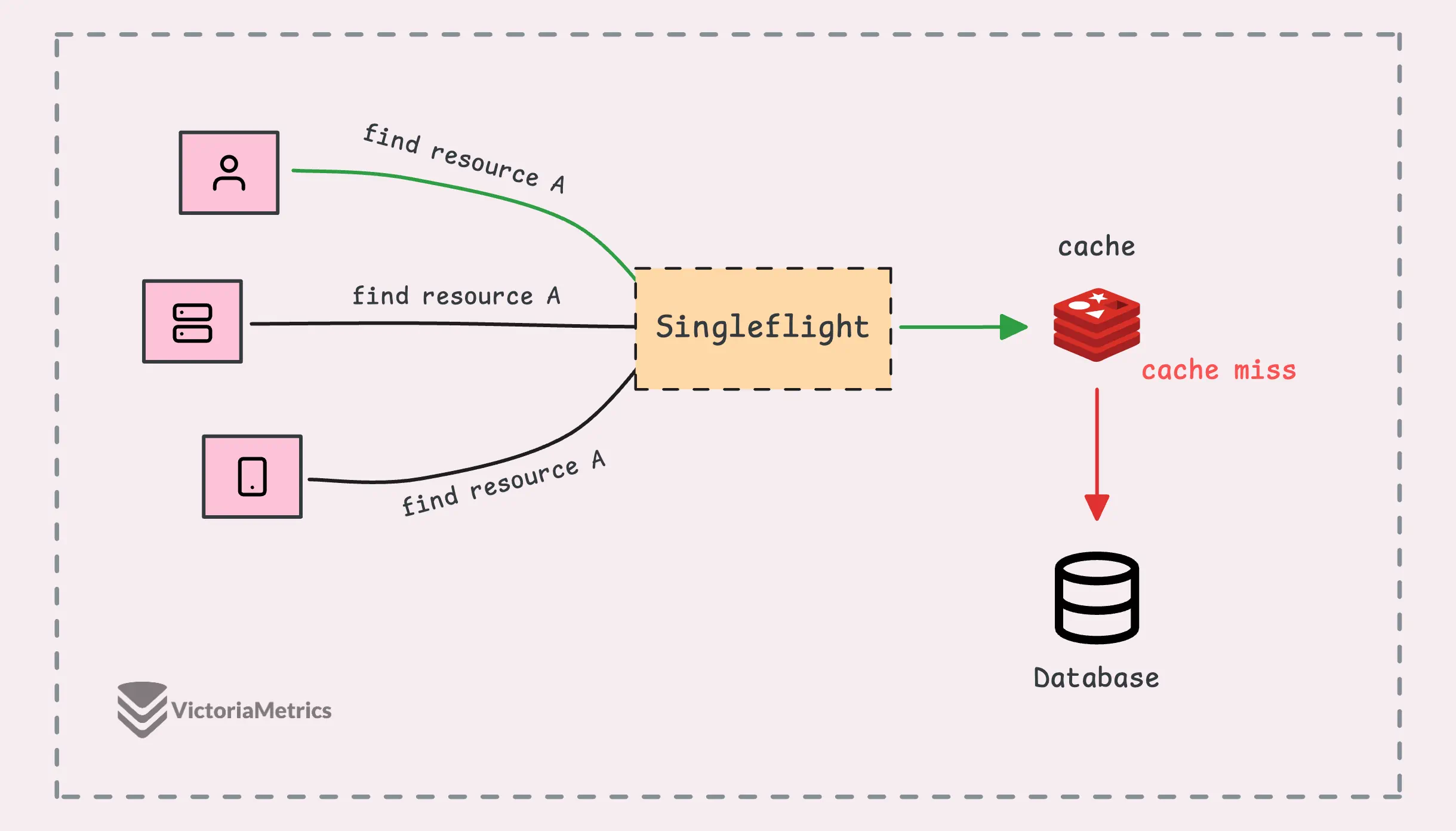

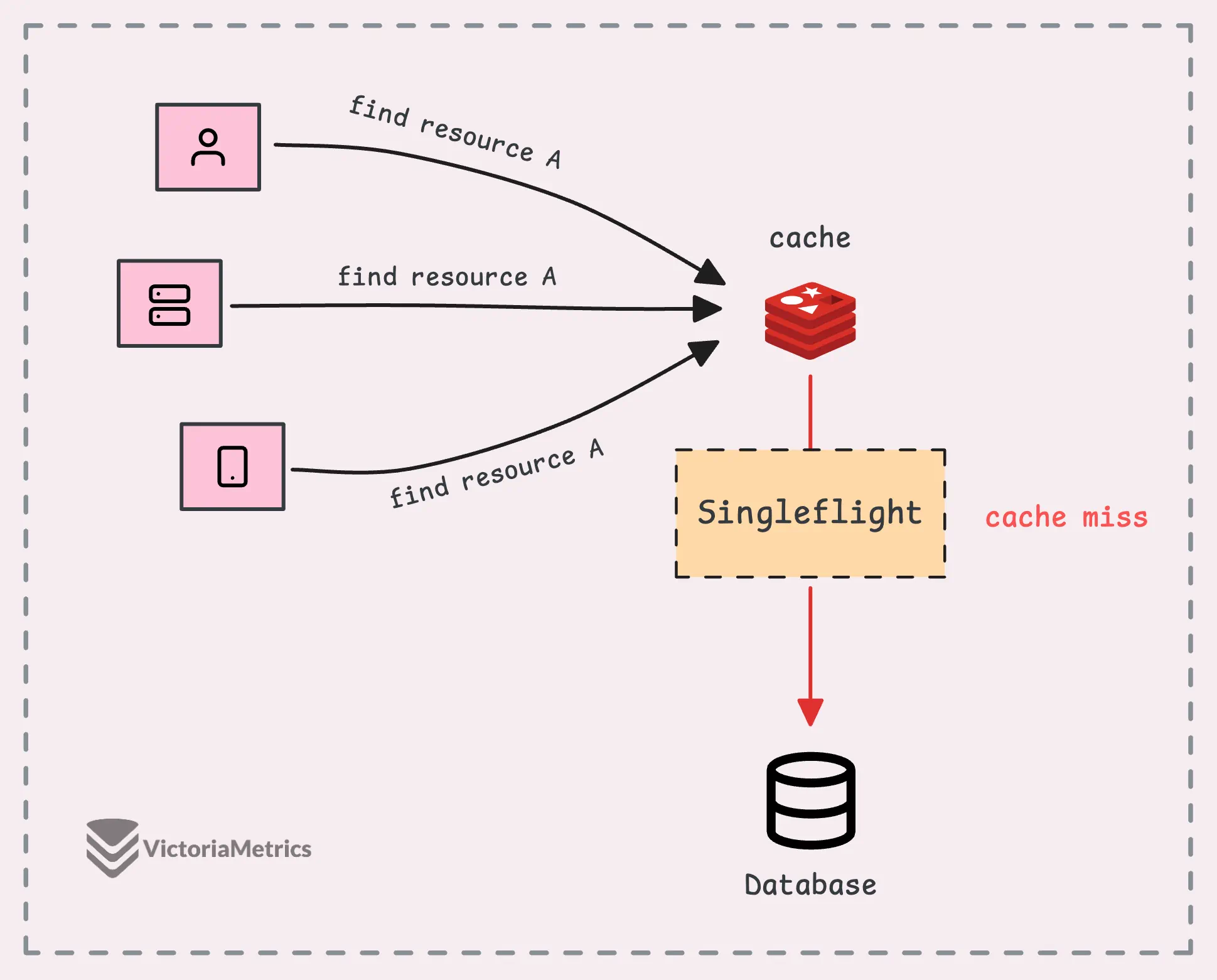

“I have a cache, why do I need singleflight?”

The short answer is: caches and singleflight solve different problems, and they actually work really well together.

In a setup with an external cache (like Redis or Memcached), singleflight adds an extra layer of protection, not just for your database but also for the cache itself.

In addition, singleflight helps protect against a cache miss storm (sometimes called a “cache stampede”).

Normally, when a request asks for data, if the data is in the cache, great—it’s a cache hit. If the data isn’t in the cache, it’s a cache miss. Suppose 10,000 requests hit the system all at once before the cache is rebuilt, the database could suddenly get slammed with 10,000 identical queries at the same time.

During this peak, singleflight ensures that only one of those 10,000 requests actually hits the database.

But later on, in the internal implementation section, we’ll see that singleflight uses a global lock to protect the map of in-flight calls, which can become a single point of contention for every goroutine. This can slow things down, especially if you’re dealing with high concurrency.

The model below might work better for machines with multiple CPUs:

Singleflight Operations

#

To use singleflight, you first create a Group object, which is the core structure that tracks ongoing function calls linked to specific keys.

It has two key methods that help prevent duplicate calls:

group.Do(key, func): Runs your function while suppressing duplicate requests. When you call Do, you pass in a key and a function, if no other execution is happening for that key, the function runs. If there’s already an execution in progress for the same key, your call blocks until the first one finishes and returns the same result.group.DoChan(key, func): Similar togroup.Do, but instead of blocking, it gives you a channel (<-chan Result). You’ll receive the result once it’s ready, making this useful if you prefer handling the result asynchronously or if you’re selecting over multiple channels.

We’ve already seen how to use g.Do() in the demo, let’s check out how to use g.DoChan() with a modified wrapper function:

// Wrap the fetchData function with singleflight using DoChan

func fetchDataWrapper(g *singleflight.Group, id int) error {

defer wg.Done()

ch := g.DoChan("key-fetch-data", fetchData)

res := <-ch

if res.Err != nil {

return res.Err

}

fmt.Printf("Goroutine %d: result: %v, shared: %v\n", id, res.Val, res.Shared)

return nil

}

package singleflight

type Result struct {

Val interface{}

Err error

Shared bool

}

To be honest, using DoChan() here doesn’t change much compared to Do(), since we’re still waiting for the result with a channel receive operation (<-ch), which is basically blocking the same way.

Where DoChan() does shine is when you want to kick off an operation and do other stuff without blocking the goroutine. For instance, you could handle timeouts or cancellations more cleanly using channels:

func fetchDataWrapperWithTimeout(g *singleflight.Group, id int) error {

defer wg.Done()

ch := g.DoChan("key-fetch-data", fetchData)

select {

case res := <-ch:

if res.Err != nil {

return res.Err

}

fmt.Printf("Goroutine %d: result: %v, shared: %v\n", id, res.Val, res.Shared)

case <-time.After(50 * time.Millisecond):

return fmt.Errorf("timeout waiting for result")

}

return nil

}

This example also brings up a few issues that you might run into in real-world scenarios:

- The first goroutine might take way longer than expected due to things like slow network responses, unresponsive databases, etc. In that case, all the other waiting goroutines are stuck for longer than you’d like. A timeout can help here, but any new requests will still end up waiting behind the first one.

- The data you’re fetching might change frequently, so by the time the first request finishes, the result could be outdated. That means we need a way to invalidate the key and trigger a new execution.

Yes, singleflight provides a way to handle situations like these with the group.Forget(key) method, which lets you discard an ongoing execution.

The Forget() method removes a key from the internal map that tracks the ongoing function calls. It’s sort of like “invalidating” the key, so if you call g.Do() again with that key, it’ll execute the function as if it were a fresh request, instead of waiting on the previous execution to finish.

Let’s update our example to use Forget() and see how many times the function actually gets called:

func fetchDataWrapperWithForget(g *singleflight.Group, id int, forget bool) error {

defer wg.Done()

// Forget the key before fetching

if forget {

g.Forget("key-fetch-data")

}

v, err, shared := g.Do("key-fetch-data", fetchData)

if err != nil {

return err

}

fmt.Printf("Goroutine %d: result: %v, shared: %v\n", id, v, shared)

return nil

}

func main() {

var g singleflight.Group

wg.Add(3)

// 2 goroutines fetch the data

go fetchDataWrapperWithForget(&g, 0, false)

go fetchDataWrapperWithForget(&g, 1, false)

// Wait a bit and launch 1 more goroutine

// Ensures goroutines 0, 1, and 2 overlap

time.Sleep(10 * time.Millisecond)

go fetchDataWrapperWithForget(&g, 2, true)

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("Function was called %d times\n", callCount.Load())

}

// Output:

// Goroutine 0: result: 55, shared: true

// Goroutine 1: result: 55, shared: true

// Goroutine 2: result: 73, shared: false

// Function was called 2 times

Goroutine 0 and Goroutine 1 both call Do() with the same key (“key-fetch-data”), and their requests get combined into one execution and the result is shared between the two goroutines.

Goroutine 2, on the other hand, calls Forget() before running Do(). This clears out any previous result tied to “key-fetch-data”, so it triggers a new execution of the function.

To sum up, while singleflight is useful, it can still have some edge cases, for example:

- If the first goroutine gets blocked for too long, all the others waiting on it will also be stuck. In such cases, using a timeout context or a select statement with a timeout can be a better option.

- If the first request returns an error or panics, that same error or panic will propagate to all the other goroutines waiting for the result.

If you have noticed all the issues we’ve discussed, let’s dive into the next section to discuss how singleflight actually works under the hood.

How Singleflight Works

#

From using singleflight, you might already have a basic idea of how it works internally, the whole implementation of singleflight is only about 150 lines of code.

Basically, every unique key gets a struct that manages its execution. If a goroutine calls Do() and finds that the key already exists, that call will be blocked until the first execution finishes, and here is the structure:

type Group struct {

mu sync.Mutex // protects the map m

m map[string]*call // maps keys to calls; lazily initialized

}

type call struct {

wg sync.WaitGroup // waits for the function execution

val interface{} // result of the function call

err error // error from the function call

dups int // number of duplicate callers

chans []chan<- Result // channels to receive the result

}

Two sync primitives are used here:

- Group mutex (

g.mu): This mutex protects the entire map of keys, not one lock per key, it makes sure adding or removing keys is thread-safe. - WaitGroup (

g.call.wg): The WaitGroup is used to wait for the first goroutine associated with a specific key to finish its work.

We’ll focus on the group.Do() method here since the other method, group.DoChan(), works in a similar way. The group.Forget() method is also simple as it just removes the key from the map.

When you call group.Do(), the first thing it does is lock the entire map of calls (g.mu).

“Isn’t that bad for performance?”

Yeah, it might not be ideal for performance in every case (always good to benchmark first) as singleflight locks the entire keys. If you’re aiming for better performance or working at a high scale, a good approach is to shard or distribute the keys. Instead of using just one singleflight group, you can spread the load across multiple groups, kind of like doing “multiflight” instead

For reference, check out this repo: shardedsingleflight.

Now, once it has the lock, the group looks that the internal map (g.m), if there’s already an ongoing or completed call for the given key. This map keeps track of any in-progress or completed work, with keys mapping to their corresponding tasks.

If the key is found (another goroutine is already running the task), instead of starting a new call, we simply increment a counter (c.dups) to track duplicate requests. The goroutine then releases the lock and waits for the original task to complete by calling call.wg.Wait() on the associated WaitGroup.

When the original task is done, this goroutine grabs the result and avoids running the task again.

func (g *Group) Do(key string, fn func() (interface{}, error)) (v interface{}, err error, shared bool) {

g.mu.Lock()

if g.m == nil {

g.m = make(map[string]*call)

}

// If the key is already exist,

// increase the duplicate counter and wait for the result

if c, ok := g.m[key]; ok {

c.dups++

g.mu.Unlock()

c.wg.Wait()

if e, ok := c.err.(*panicError); ok {

panic(e)

} else if c.err == errGoexit {

runtime.Goexit()

}

return c.val, c.err, true

}

// Otherwise, create a new call and add it to the map

c := new(call)

c.wg.Add(1)

g.m[key] = c

g.mu.Unlock()

// Execute the function

g.doCall(c, key, fn)

return c.val, c.err, c.dups > 0

}

If no other goroutine is working on that key, the current goroutine takes responsibility for executing the task.

At this point, we create a new call object, add it to the map, and initialize its WaitGroup. Then, we unlock the mutex and proceed to execute the task ourselves via a helper method g.doCall(c, key, fn). When the task completes, any waiting goroutines are unblocked by the wg.Wait() call.

Nothing too wild here, except for how we handle errors, there are three possible scenarios:

- If the function panics, we catch it, wrap it in a

panicError, and throw the panic. - If the function returns an

errGoexit, we callruntime.Goexit()to properly exit the goroutine. - If it’s just a normal error, we set that error on the call.

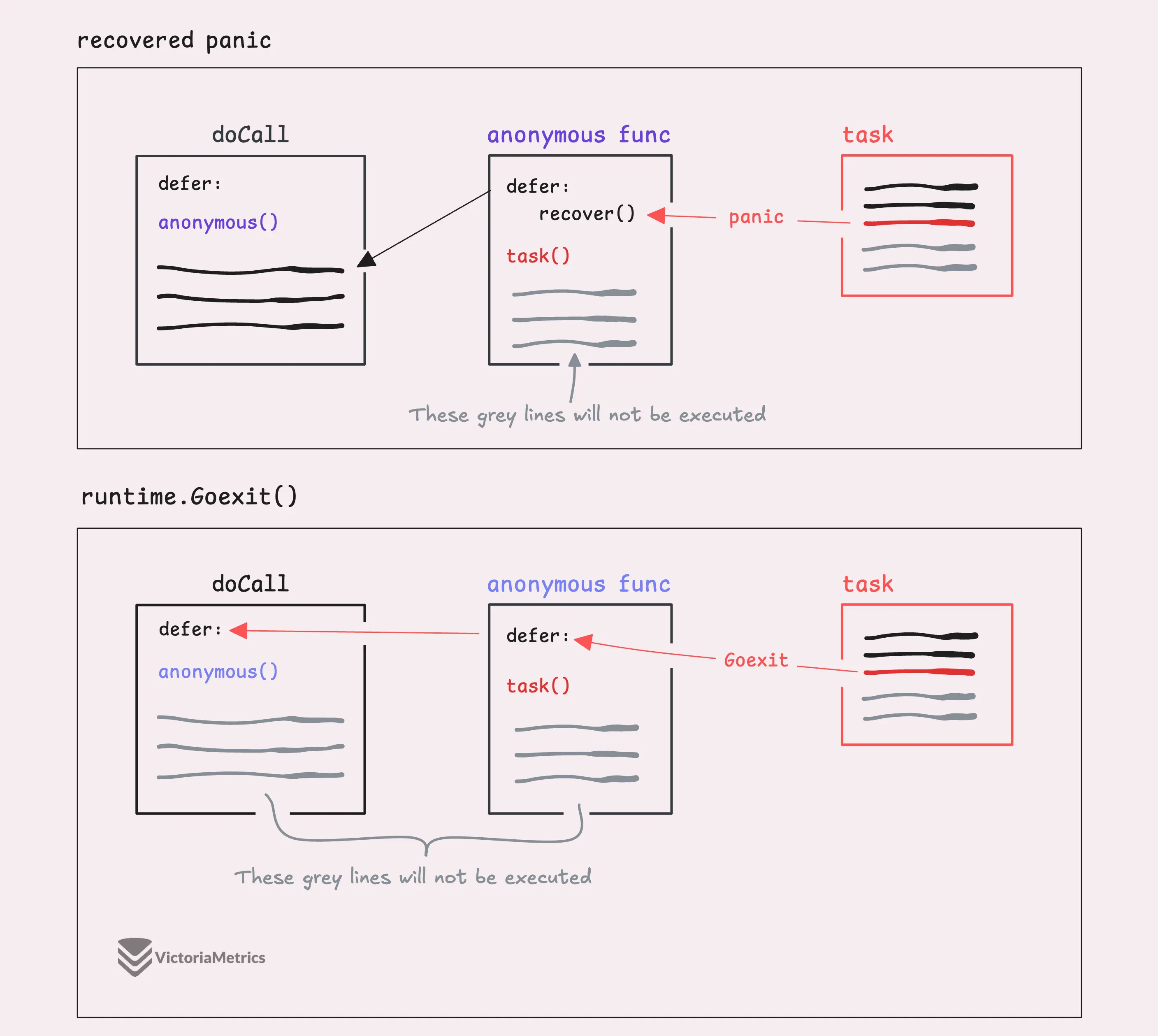

This is where things start to get a little more clever in the helper method g.doCall().

“Wait, what’s

runtime.Goexit()?”

Before we dive into the code, let me quickly explain, runtime.Goexit() is used to stop the execution of a goroutine.

When a goroutine calls Goexit(), it stops, and any deferred functions are still run in Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) order, just like normal. It’s similar to a panic, but there are a couple of differences:

- It doesn’t trigger a panic, so you can’t catch it with

recover(). - Only the goroutine that calls

Goexit()gets terminated and all the other goroutines keep running just fine.

Now, here’s an interesting quirk (not directly related to our topic, but worth mentioning). If you call runtime.Goexit() in the main goroutine (like inside main()), check this out:

func main() {

go func() {

println("goroutine called")

}()

runtime.Goexit()

println("main goroutine called")

}

// Output:

// goroutine called

// fatal error: no goroutines (main called runtime.Goexit) - deadlock!

What happens is that Goexit() terminates the main goroutine, but if there are other goroutines still running, the program keeps going because the Go runtime stays alive as long as at least one goroutine is active. However, once no goroutines are left, it crashes with a “no goroutines” error, kind of a fun little corner case.

Now, back to our code, if runtime.Goexit() only terminates the current goroutine and can’t be caught by recover(), how do we detect if it’s been called?

The key lies in the fact that when runtime.Goexit() is invoked, any code after it doesn’t get executed.

func main() {

normalReturn := false

defer func() {

if !normalReturn {

println("runtime.Goexit() called")

return

}

println("normal return")

}()

runtime.Goexit()

normalReturn = true

}

// Output:

// runtime.Goexit() called

// fatal error: no goroutines (main called runtime.Goexit) - deadlock!

In the above case, the line normalReturn = true never gets executed after calling runtime.Goexit(). So, inside the defer, we can check whether normalReturn is still false to detect that special method was called.

The next step is figuring out if the task is panicking or not. For that, we use recover() as normal return, though the actual code in singleflight is a little more subtle:

// doCall handles the single call for a key.

func (g *Group) doCall(c *call, key string, fn func() (interface{}, error)) {

normalReturn := false

recovered := false

defer func() {

// The case of calling runtime.Goexit() in the task

if !normalReturn && !recovered {

c.err = errGoexit

}

... // handle each cases

}()

func() {

defer func() {

if !normalReturn {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

c.err = newPanicError(r)

}

}

}()

c.val, c.err = fn()

normalReturn = true

}()

if !normalReturn {

recovered = true

}

}

Instead of setting recovered = true directly inside the recover block, this code gets a little fancy by setting recovered after the recover() block as the last line.

So, why does this work?

When runtime.Goexit() is called, it terminates the entire goroutine, just like a panic(). However, if a panic() is recovered, only the chain of functions between the panic() and the recover() is terminated, not the entire goroutine.

That’s why recovered = true gets set outside the defer containing recover(), it only gets executed in two cases: when the function completes normally or when a panic is recovered, but not when runtime.Goexit() is called.

Moving forward, we’ll discuss how each case is handled.

func (g *Group) doCall(c *call, key string, fn func() (interface{}, error)) {

...

defer func() {

...

// Lock and remove the call from the map

g.mu.Lock()

defer g.mu.Unlock()

c.wg.Done()

if g.m[key] == c {

delete(g.m, key)

}

if e, ok := c.err.(*panicError); ok {

if len(c.chans) > 0 {

go panic(e)

select {} // Keep this goroutine around so that it will appear in the crash dump.

} else {

panic(e)

}

} else if c.err == errGoexit {

// Already in the process of goexit, no need to call again

} else {

// Normal return

for _, ch := range c.chans {

ch <- Result{c.val, c.err, c.dups > 0}

}

}

}()

...

}

If the task panics during execution, the panic is caught and saved in c.err as a panicError, which holds both the panic value and the stack trace. singleflight catches the panic to clean up gracefully, but it doesn’t swallow it, it rethrows the panic after handling its state.

That means the panic will happen in the goroutine that’s executing the task (the first one to kick off the operation), and all the other goroutines waiting for the result will also panic.

Since this panic happens in the developer’s code, it’s on us to deal with it properly.

Now, there’s still a special case we need to consider: when other goroutines are using the group.DoChan() method and waiting on a result via a channel. In this case, singleflight can’t panic in those goroutines. Instead, it does what’s called an unrecoverable panic (go panic(e)), which makes our application crash.

Finally, if the task called runtime.Goexit(), there’s no need to take any further action because the goroutine is already in the process of shutting down, and we just let that happen without interfering.

And that’s pretty much it, nothing too complicated except for the special cases we’ve discussed.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.