- Blog /

- Go Runtime Finalizer and Keep Alive

Go Runtime Finalizer and Keep Alive

1. Finalizer

#

So, here’s something interesting, there’s an API in Go’s runtime package called runtime.SetFinalizer. This little feature lets you set a “finalizer” for an object.

Now, a finalizer is basically a function tied to an object that’s meant to run once the garbage collector decides that the object’s no longer needed.

type FourInts struct {

A int; B int; C int; D int

}

func final() {

a := &FourInts{}

runtime.SetFinalizer(a, func(a *FourInts) {

fmt.Println("finalizer of FourInts called")

})

}

func main() {

final()

runtime.GC()

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond)

}

// Output: finalizer of FourInts called

In this code, I’ve got a pointer referencing an instance of a FourInts struct, and then I set a finalizer for it. So, when the garbage collector runs, it’ll call the finalizer once that object is no longer needed, which in this case means printing out a message.

Pretty cool, right?

The catch here is that with this setup, our instance a is getting allocated on the heap.

Now, Go’s garbage collector will eventually trigger the finalizer, but it won’t happen exactly when the object’s no longer in use. The finalizer will run, but there’s no specific guarantee on timing. It’s unpredictable, meaning you can’t count on it for any immediate actions.

Since Go’s garbage collector operates behind the scenes, the timing of finalizers depends entirely on the GC cycle. This unpredictability gives finalizers a kind of “magic” quality that, well, we Gophers tend not to be big fans of. Go doesn’t really encourage using finalizers like destructors in other languages, mainly because relying on them this way can lead to memory leaks if GC doesn’t happen when you’re hoping it will.

Here’s a quick example to illustrate just how unpredictable finalizers can be:

type FourBytes struct {

A byte; B byte; C byte; D byte

}

func final() {

a := &FourBytes{}

runtime.SetFinalizer(a, func(a *FourBytes) {

fmt.Println("finalizer of FourBytes called")

})

}

func main() {

final()

runtime.GC()

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond)

}

Give it a try here: https://go.dev/play/p/9EkDLsj-tse

Surprisingly, nothing prints out. And all we did was switch from a FourInts struct to a FourBytes struct with byte fields. So, what’s going on here?

Actually, that code snippet above can be a bit unreliable, it might print the finalizer message, or it might stay totally silent. Switching from four integers to four bytes shrinks the object, and that, in turn, changes how Go’s runtime allocator handles it.

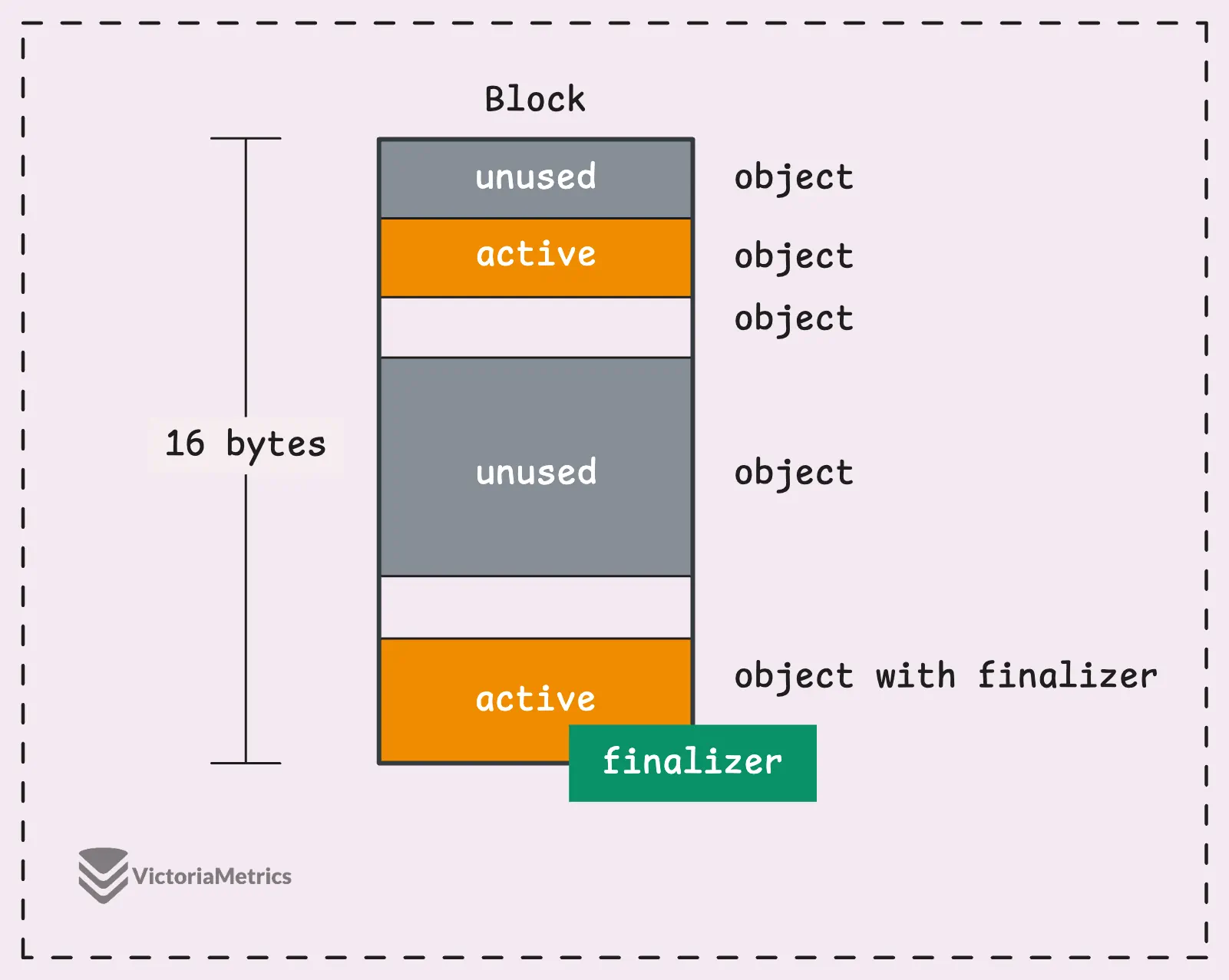

The FourBytes (4 bytes) is considered as tiny object, Go packs multiple tiny objects into a single block.

This batching has an odd side effect, the finalizer for any one object in that pack might never run if any object in the batch is still being used. Basically, Go sees the entire batch as “in use” as long as at least one object in it is still around.

To qualify as a “tiny object,” it has to be smaller than 16 KB, and it can’t contain or relate to any pointers.

“So, should we avoid finalizers altogether?”

Honestly, if you find yourself needing to use finalizers, there’s a good chance it’s a sign of a design issue. But that said, there’s nothing inherently wrong with using them when it’s the right tool for the job.

There’s definitely a pattern here, especially for anyone writing libraries. A good way to avoid finalizer “magic” is to provide an explicit function along with a backup plan in the finalizer:

- Create a method like

Close,Release,Dispose(whatever you prefer) so users have a way to release resources programmatically, giving them control rather than leaving things up to the garbage collector. - Then, use the finalizer as a fallback to ensure resources get freed if users slip up, maybe with a warning log that points to the specific file and line to help track down any resource leaks.

In short, finalizers should be the safety net, not a replacement for explicit cleanup. This pattern is actually discussed in the article Go I/O Closer, Seeker, WriterTo, and ReaderFrom where I mentioned os.File.

Let’s take a quick step back here:

When you create an os.File, Go actually sets up a finalizer to automatically close() the file descriptor when it’s no longer needed:

func newFile(fd int, name string, kind newFileKind, nonBlocking bool) *File {

f := &File{&file{

pfd: poll.FD{

Sysfd: fd,

IsStream: true,

ZeroReadIsEOF: true,

},

name: name,

stdoutOrErr: fd == 1 || fd == 2,

}}

...

runtime.SetFinalizer(f.file, (*file).close)

return f

}

Now, if you call Close() explicitly, it goes through the same steps, eventually calling close() and then clearing out the finalizer:

func (file *file) close() error {

...

// no need for a finalizer anymore

runtime.SetFinalizer(file, nil)

return err

}

A quick warning here: when your program ends, Go doesn’t trigger a GC cycle just to run finalizers. So, if your program finishes before the GC kicks in again, any pending finalizers won’t run at all.

From this pattern, we can see Go only allows one finalizer per object at a time. If you try adding another, it will simply replace the first one, and you can remove a finalizer by setting it to nil.

“Once a finalizer runs, the object technically isn’t supposed to be reused, but what if we go ahead and do it anyway?”

This brings us into the interesting, tricky—territory of “object resurrection,” which is one reason why finalizers are often discouraged.

Object resurrection happens when an object that the garbage collector (GC) has marked as unreachable somehow gets a new reference, bringing it back into the reachable pool and blocking its cleanup. This can happen in languages that support finalizers, including Go.

Under the hood, when Go’s GC finds an unreachable object with a finalizer, it’ll call that finalizer but won’t immediately free up the object. Inside the finalizer, you still have access to the object, and if the finalizer creates a new reference to it, maybe by assigning it to a global variable or another live structure, the object becomes reachable again.

To prevent issues, Go delays the actual memory cleanup until the next GC cycle:

- In the first GC pass, the object is flagged as reachable and its finalizer is executed. That said, the object is marked as reachable during this cycle, with or without a reference in the finalizer.

- In the second GC pass, if the object is unreachable, it finally gets cleared out.

This whole setup is why finalizers aren’t exactly beginner-friendly, you really need some Go experience to use them safely. Without it, you could easily crash your program:

type FourInt struct {

A int

B *int

C int

D int

}

func final() {

a := &FourInt{}

runtime.SetFinalizer(&a.B, func(b **int) {

fmt.Println("finalizer of FourInt.B called")

})

}

func main() {

final()

runtime.GC()

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond)

}

// fatal error: runtime.SetFinalizer: pointer not at beginning of allocated block

I adjusted the struct here so that B is now a pointer to an int, and set a finalizer for a.B instead of a.

As a result, the program crashes with a fatal error, and there’s no recovery from this.

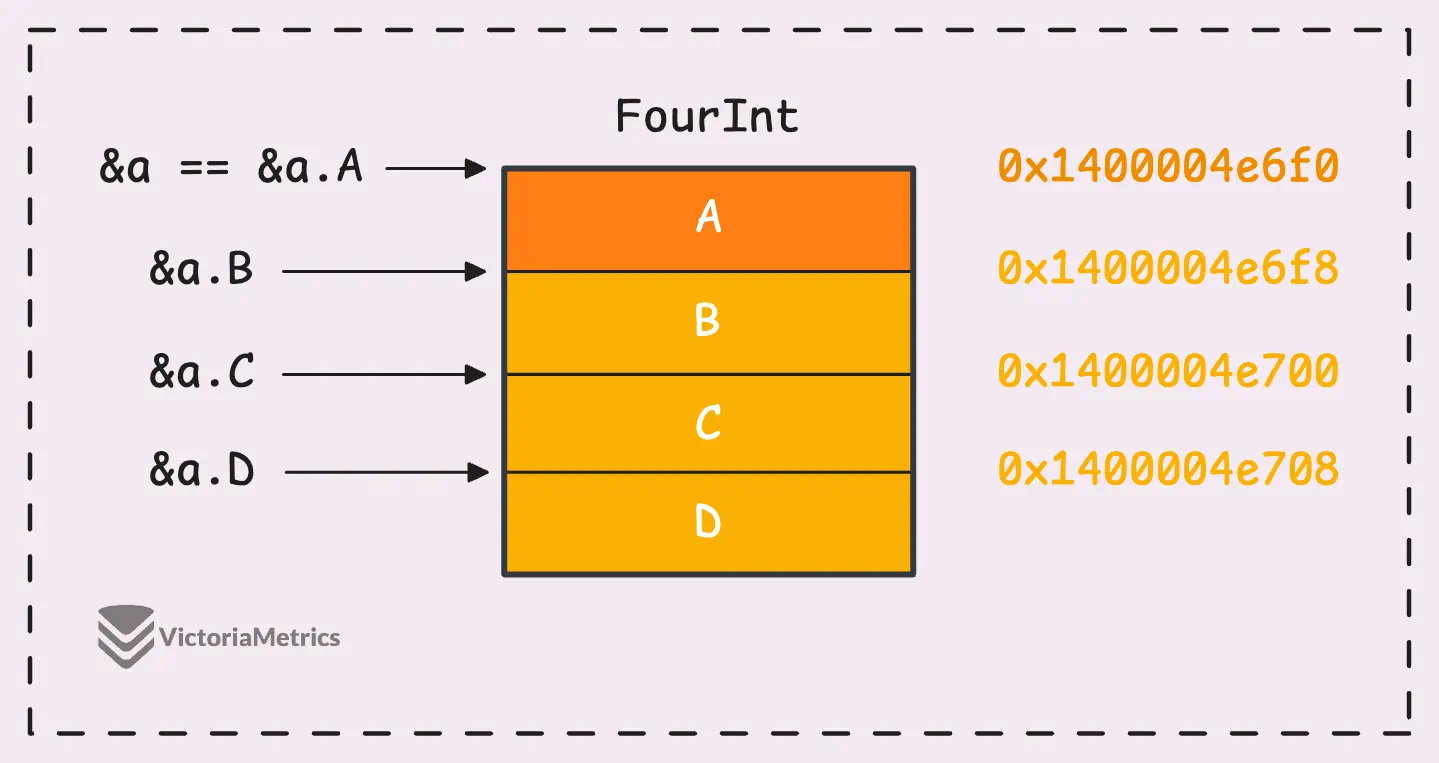

This brings up another requirement with runtime.SetFinalizer: the finalizer should be attached to the first word (or the beginning) of the memory block. In this case, a.B isn’t the start of the block; it’s just a part of it.

What this means is that if you set a finalizer for FourInt.A, and FourInt.A happens to be a pointer, then it all works just fine because FourInt.A and FourInt share the same starting address.

Let’s switch B back to being an int and try setting a finalizer on it again, let’s see what happens:

type FourInt struct {

A int

B int

C int

D int

}

func final() {

a := &FourInt{}

runtime.SetFinalizer(&a.B, func(b *int) {

fmt.Println("finalizer of FourInt.B called")

})

}

func main() {

final()

runtime.GC()

time.Sleep(time.Millisecond)

}

// Output: finalizer of FourInt.B called

The program now runs without crashing, and the finalizer is called as expected.

But wait, didn’t I just mention that SetFinalizer would crash if the object wasn’t at the start of the memory block?

Turns out, tiny objects are an exception to this rule. Here, FourInt.B isn’t a pointer, and at 8 bytes, it’s below the 16-byte threshold, qualifying as a tiny object.

So, in the end, while finalizers are handy for adding a backup layer, their unpredictability and unintuitive behavior make them a poor choice for routine use. In fact, there’s an accepted proposal to deprecate finalizers in favor of a new API called AddCleanup — we’ll definitely get into that later.

2. Keep Alive

#

The next API in Go’s runtime package worth discussing is runtime.KeepAlive. The name says it all — it keeps an object alive to prevent it from being collected by the garbage collector. But the reason why you’d need this isn’t all that obvious.

Let’s go back to the File example, but this time, we’ll simulate it instead of using os.File directly:

type File struct {

fd int

_ [2]int

}

func OpenFile() *File {

f := &File{fd: rand.Int() % 100}

runtime.SetFinalizer(f, func(b *File) {

fmt.Println("Closing file with fd", b.fd)

})

return f

}

func doingSomethingWithFile(fd int) {

runtime.GC()

fmt.Printf("Doing something with file with fd %d\n", fd)

}

func main() {

f := OpenFile()

doingSomethingWithFile(f.fd)

}

// Output:

// Closing file with fd 25

// Doing something with file with fd 25

Try it here: https://go.dev/play/p/rVprMIlx2qb

For those unfamiliar with file handling, here’s a quick rundown: when your application opens a file, the OS gives it a file descriptor (or fd). This number is like a handle for the file, allowing your application to perform actions (read, write, close) without directly managing the file itself.

Now, back to the example and here’s how it plays out:

- When opening the file, we set up a finalizer to close the file descriptor when

fis no longer needed. By now, this pattern probably looks familiar. - When calling

doingSomethingWithFile, the garbage collector runs and ends up collectingf, the file we just opened. - The finalizer runs and closes the file descriptor, printing: “Closing file with fd 25”.

- Finally, we’re still trying to work with the file descriptor, but it’s already closed. So we print: “Doing something with file with fd 25”.

Basically, the finalizer ran too soon, closing the file associated with fd while doingSomethingWithFile was still expecting it to be open.

“Why does this happen? We’re still using

finmain, so how could it be collected?”

While it’s clear to us that f is being used in main, so it shouldn’t be collected during doingSomethingWithFile, the compiler sees things differently.

After we pass f.fd to doingSomethingWithFile, the compiler considers f no longer in use and allows the garbage collector to treat it as eligible for collection. The GC does its thing, and the finalizer gets triggered.

You can probably guess the fix, we just need to keep f around until doingSomethingWithFile is done with it.

func main() {

f := OpenFile()

doingSomethingWithFile(f.fd)

runtime.KeepAlive(f)

}

Try it here: https://go.dev/play/p/yCChTvjP3pl

By adding runtime.KeepAlive(f) at the end of main, we ensure that f stays “alive” until that line, preventing premature finalization.

runtime.KeepAlive isn’t complicated to understand, it simply creates a reference to the object, keeping it “alive” by ensuring there’s still an explicit reference in your code. This function is backed by the runtime specifically to avoid optimizations like inlining, removing unused code, etc.

According to Go’s documentation, runtime.KeepAlive is mainly useful for avoiding situations where the finalizer runs too soon.

Congratulations on making it this far! Now you know more about Go’s internals — funny how a language can start to feel a little less familiar the deeper you go.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus