- Blog /

- Practical Protobuf - From Basic to Best Practices

Practical Protobuf - From Basic to Best Practices

This article is part of the series on communication protocols:

- From net/rpc to gRPC in Go Applications

- How HTTP/2 Works and How to Enable It in Go

- Practical Protobuf - From Basic to Best Practices (We’re here)

- How Protobuf Works—The Art of Data Encoding

- gRPC in Go: Streaming RPCs, Interceptors, and Metadata

Protocol Buffers, or Protobuf for short, is Google’s language-neutral data serialization format.

You define the structure of your message in a .proto file, following its syntax rules. From there, Protobuf knows how to convert that message into a compact, binary format—much smaller than JSON or XML, in fact. And when you need it back, Protobuf can deserialize it into the original message, with backward compatibility intact (unless you break it yourself).

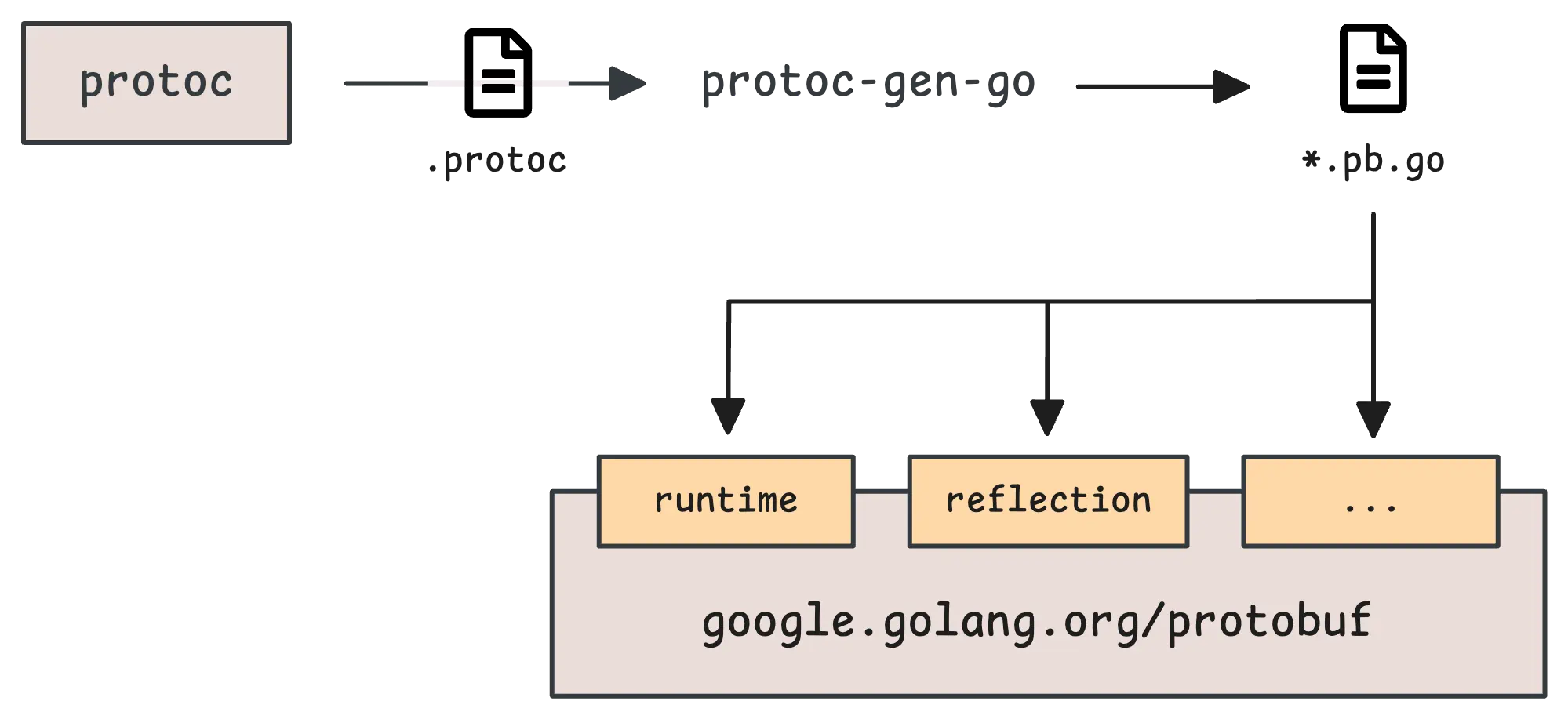

When it comes to defining and generating a Protobuf message, there are 3 main pieces at play:

- The main compiler: First up, there’s

protoc. This is the core compiler for Protobuf. It reads your.protofiles and generates code in various languages like Go, Java, Python, C++, and so on. Butprotocdoesn’t know how to handle every language out of the box. For certain languages (e.g. Go, Dart), you’ll need specific plugins to help it out. - Language-specific plugins: That’s where plugins like

protoc-gen-goorprotoc-gen-dartcome in. These are called byprotocbehind the scenes to generate the right kind of code—so, for Go, you’ll get a.pb.gofile. Other languages follow their own patterns: JavaScript might give you a*_pb.js, and Python would typically generate a*_pb2.py. - The runtime library: Once your Go code is generated, it doesn’t just work on its own. It needs a runtime library to function. That’s where the Go Protobuf library (

google.golang.org/protobuf) steps in. Your.pb.gofiles will depend on this library for things like serialization, deserialization, and everything in between.

This discussion is about how to write your .proto file—and how to use it with good practice in mind.

Message & Tag

#

In Protobuf, a message is the unit structure that defines the data you’ll be sending between different systems or services:

message Person {

string name = 1;

int32 id = 2;

string email = 3;

}

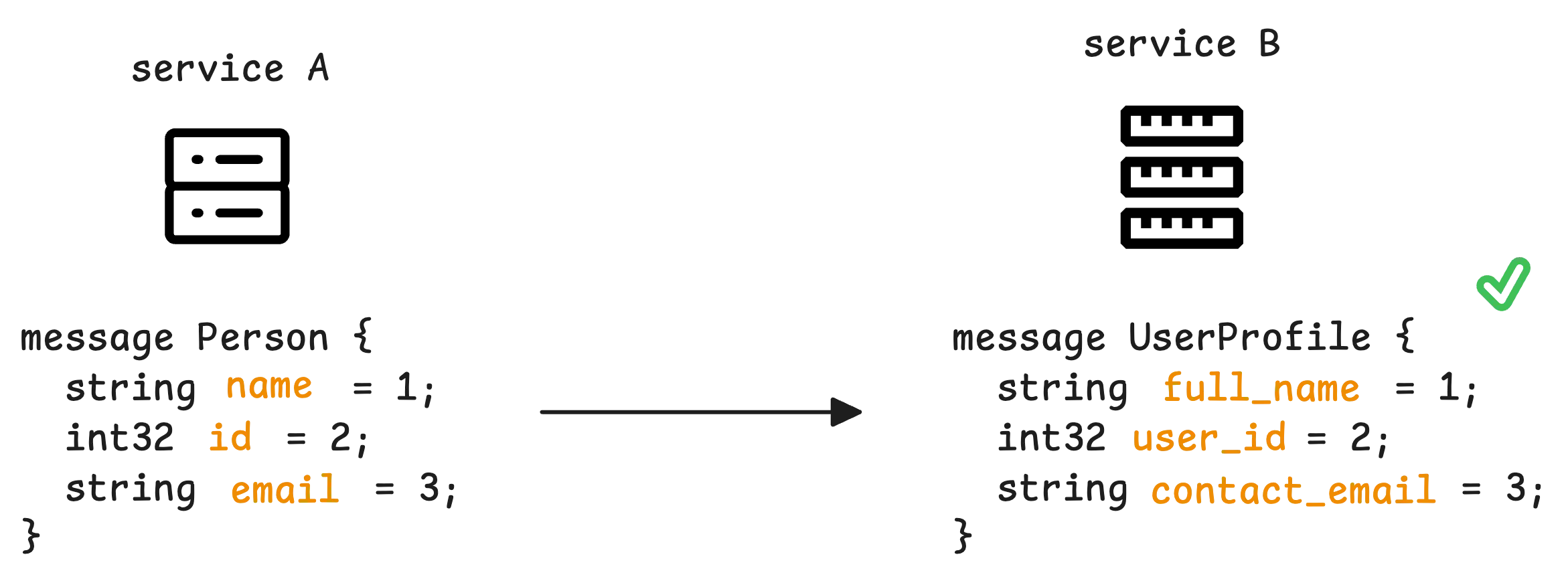

Every field inside a message has two key parts: a type and a tag number. Together, these form a unique identifier for that field.

The tag number tells Protobuf where to find that piece of data inside the message. Interestingly, the field name—whether it’s name, id, or anything else—doesn’t really matter in most cases:

Two systems can still communicate perfectly, even if you change the field name, as long as the tag number and type stay the same.

That said, if you decide to remove a field from a message and delete it from your .proto file, there’s something important to consider. Old code might still expect that field to exist with the same tag number. To prevent unexpected issues down the line, it’s best to reserve that tag number (and optionally, the field name) so it doesn’t accidentally get reused.

This is done by using the reserved keyword right inside your message definition:

message Person {

reserved 2, 3;

reserved "email", "id";

string name = 1;

int32 age = 4;

}

If you accidentally reuse a reserved tag number, protoc will yell at you during compilation with something like: “Field ‘email’ uses reserved number 3.”

Question!

“Why reserve the field name?”

Even though Protobuf mainly relies on tag numbers—not field names—there’s a catch when working with systems like gRPC that convert Protobuf messages into JSON (or other text-based formats) for interoperability. In those cases, field names do matter. It’s also a good practice to avoid relying on text-based serialization altogether.

One last thing—don’t throw around tag numbers randomly. Larger tag numbers require more bytes to encode. Ideally, keep them between 1 and 15 so they can fit within a single byte.

Types

#

Scalar Types

#

Protobuf supports a variety of scalar types. They might seem similar, especially when it comes to the range of values they can hold. But the real difference lies in how they’re serialized.

First, let’s break them down quickly:

int32,int64,uint32,uint64: Standard integer types, using variable-length encoding. Smaller values take up fewer bytes.fixed32,fixed64,sfixed32,sfixed64: These work similarly in terms of meaning but handle serialization differently. They always use a fixed amount of space—4 bytes forfixed32and 8 bytes forfixed64.sint32,sint64: Signed integers that use ZigZag encoding—this technique makes negative numbers more efficient by reducing the number of bytes needed.float,double: Standard floating-point numbers.bool: Stored as a single byte to representtrueorfalse. It’s encoded similarly toint32using varint encoding.string: UTF-8 encoded string.bytes: A sequence of bytes.

Out of all these, the first three groups deserve a closer look—they can be a bit less obvious in how they’re actually used.

Take int32 and its relatives—they’re great for small numbers. For example, the number 1 will only take up 1 byte with int32, while fixed32 will always use 4 bytes, no matter what. But things change when you start dealing with larger values.

In fact, bigger numbers can end up taking more space with int32 family than if you just went with fixed32 family:

encode_int32(1 << 28) = [128 128 128 128 1]

encode_fixed32(1 << 28) = [0 0 0 16]

Once you hit 2^28 (268,435,456), the int32 family starts using 5 bytes, while fixed32 stays consistent at 4 bytes. So, if you’re storing large numbers—like seconds since the Unix epoch—fixed32 is the better choice.

There’s another important downside with the int32 family: handling negative numbers.

If you’re using int32 or int64 and try to encode -1, it ends up using a whopping 10 bytes. Meanwhile, sint32—thanks to ZigZag encoding—only needs 1 byte to handle the same value.

encode_int32(-1) = [255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 1]

encode_int64(-1) = [255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 255 1]

encode_sint32(-1) = [1]

So, if you’re not entirely sure about the range of values your data will cover, sticking with the sint32 family by default is a safer bet.

Tip

To learn more about encoding, you can read the next part of the series: How Protobuf Works—The Art of Data Encoding.

Enums

#

Enums let you define a set of named values—essentially a way to assign readable labels to specific numbers:

enum Version {

VERSION_UNSPECIFIED = 0;

VERSION_PROTO1 = 1;

VERSION_PROTO2 = 2;

VERSION_PROTO3 = 3;

VERSION_EDITION2023 = 4;

}

By default, enums start with the value 0. It’s a good idea to reserve that zero for an unspecified state—something like VERSION_UNSPECIFIED to act as a fallback for when no valid value is set.

Let’s build on that idea with a more advanced example:

enum Version {

option allow_alias = true;

reserved 1;

reserved "VERSION_PROTO1";

VERSION_UNSPECIFIED = 0;

VERSION_PROTO2 = 2;

VERSION_PROTO3 = 3;

VERSION_EDITION2023 = 4;

VERSION_LATEST = 4;

}

In some cases, you might want different names to share the same numeric value. Take VERSION_LATEST in this example—it shares the value 4 with VERSION_EDITION2023. This is called an alias.

By default, Protobuf doesn’t allow aliases, so if you want to enable this behavior, you’ll need to set option allow_alias = true; in the enum definition.

When it comes to serialization, enums work just like the int32 family. That means they’re not great for negative numbers—so best to keep your enum values non-negative.

Question:

“How does the compiler know which alias to use when deserializing an enum value?”

Say you serialize the enum value VERSION_LATEST into binary:

When that data gets read back, and Protobuf hits the numeric value 4, it assigns the value to the first matching enum name it finds.

In this case, that would be VERSION_EDITION2023. In most languages, this isn’t an issue, but it’s something worth keeping in mind depending on your use case.

Interestingly, you can also use the reserved keyword with enums, just like you do with messages. In messages, you reserve the tag number; with enums, you reserve the value itself.

Note

The enum above is defined in proto3, where you can reserve names directly using quotes—like reserved "VERSION_PROTO1";. But in edition 2023, that syntax isn’t allowed anymore. Instead, you’ll need to use reserved VERSION_PROTO1; without the quotes.

Repeated

#

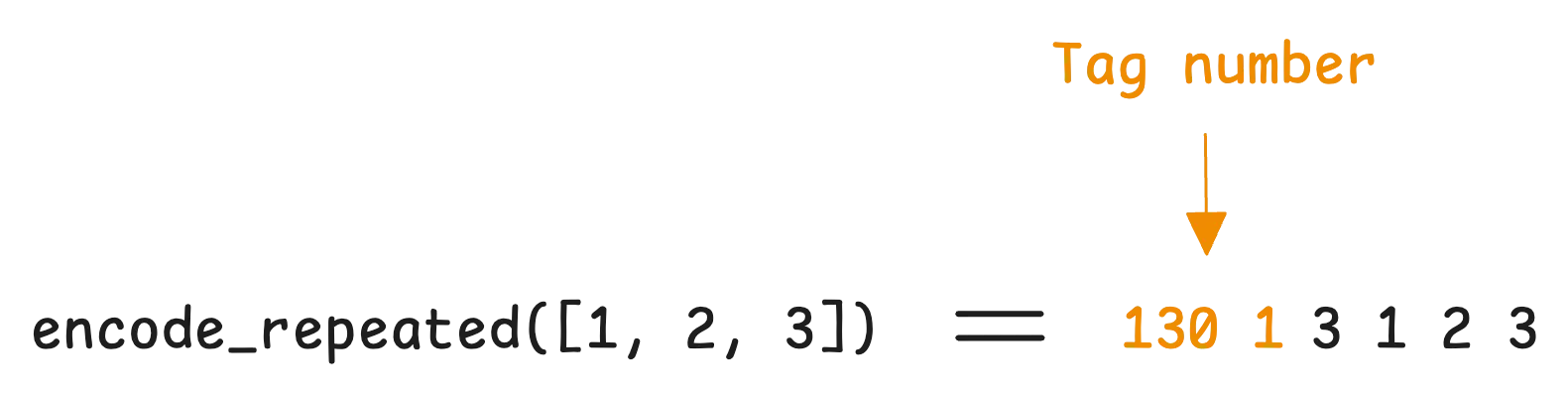

A repeated field holds multiple values of the same type. It works like an array or list in most programming languages, and the order of elements is always preserved.

message Person {

string name = 1;

repeated string emails = 16;

}

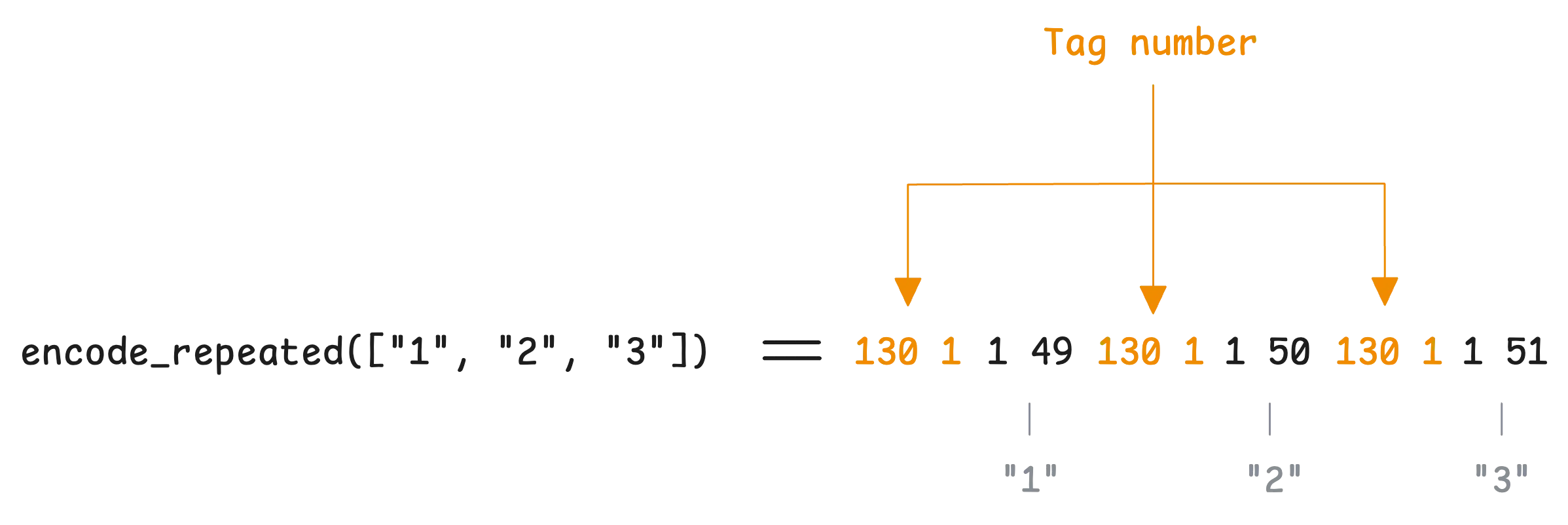

This snippet works, but it’s not a great practice. We already discussed that using tag numbers outside the range of 1 to 15 isn’t ideal because larger tag numbers take up more space. But it gets even worse when you use them with repeated fields since the tag number will be written for every single element.

If you have a list of hundreds of emails, that tag number 16 will get encoded again and again for each entry. Not exactly efficient.

So, if you’re dealing with many fields, it’s better to move your repeated fields toward the top of your message, using lower tag numbers where possible.

Luckily, there’s a way to avoid this overhead. Packing allows any repeated scalar type (except string and bytes) to only write the tag number once in the serialized data, no matter how many elements you have. This feature is turned on by default in proto3 and edition 2023. If you’re using proto2, you’ll need to enable it manually by adding [packed=true].

Of course, our repeated string above can’t be packed, but a repeated array of numbers can:

Note

This is by default enabled in proto3 and edition 2023 but you need to turn it on explicitly in proto2 [packed=true].

Maps

#

A map lets you store key-value pairs—pretty much like a dictionary or hash map in most programming languages:

message Person {

string name = 1;

map<string, string> emails = 2;

}

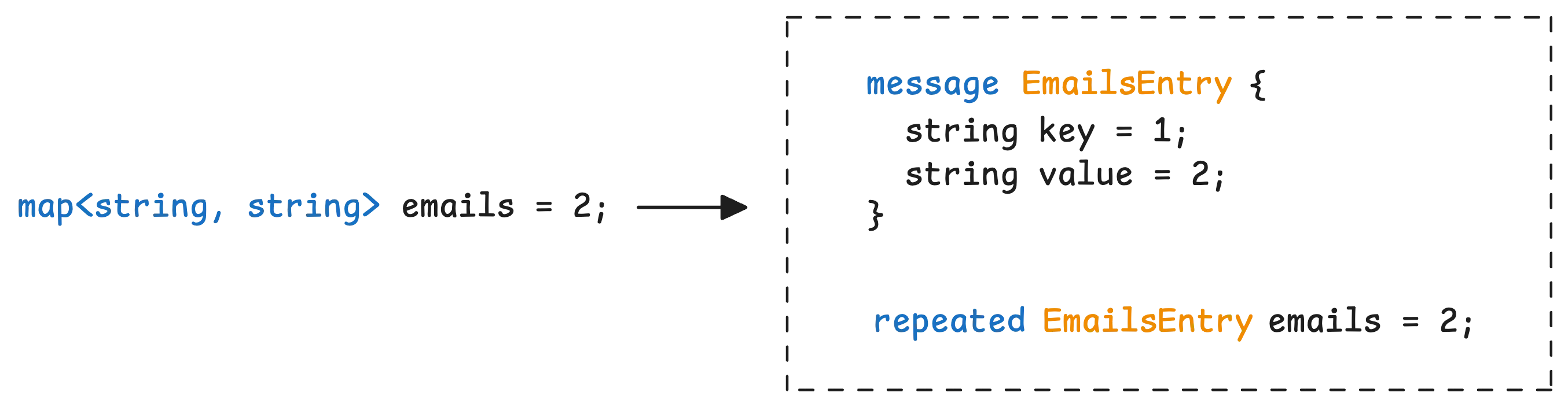

It might seem like map is its own special type in Protobuf—but that’s not actually the case. Under the hood, Protobuf handles maps by generating a message with two fields: key and value.

Then, it uses a repeated field to store multiple entries of that message.

Oneof

#

oneof lets you define several fields in a message, but with one rule: only one of those fields can be set at any given time:

message Notification {

string message = 1;

oneof notification_type {

string email = 2;

string sms = 3;

string push = 4;

}

}

If you set the email field, the sms and push fields will automatically be cleared. Only one can hold a value—whichever was set last.

When serialized, only the field that is set (i.e., the one holding a value) is included in the serialized output. The other fields within the oneof are omitted from the wire format.

If, for some reason, two fields from the same oneof end up being provided (which technically shouldn’t happen), the last field encountered in the serialized data determines the active field in the parsed message. That field will “win” and be the one that actually holds the value after deserialization.

google.protobuf.*

#

Protobuf comes with a set of predefined message types, known as well-known types, all packaged under google.protobuf. These are built to handle common scenarios and make defining standard message structures a lot simpler. For instance:

google.protobuf.Timestamp: represents a specific point in time, accurate down to the nanosecond. It stores time as seconds and nanoseconds since the Unix epoch.google.protobuf.Duration: represents a time span—basically, a length of time—not tied to any calendar or clock.google.protobuf.Int32Value,google.protobuf.Int64Value: and similar types wrap primitive values like int32, int64, string, bool, and so on.

In earlier versions of proto3 syntax, primitive fields didn’t support presence. This meant you couldn’t tell if a field was actually set or if it just held a default value (like 0 for integers). To work around this, developers often used wrapper types because these message types naturally support presence tracking.

For example, in Go, these wrappers show up as pointers—so you can easily tell whether a field is nil (not set) or actually holding a zero value.

You can find all of these well-known types in the official Protocol Buffers Well-Known Types documentation.

Services

#

Protocol Buffers (Protobuf) allows you to define the structure of services and their methods in your .proto files.

service MonitoringService {

rpc GetMetrics(MetricsRequest) returns (MetricsResponse);

}

This defines a service with one method, GetMetrics, which takes a MetricsRequest and returns a MetricsResponse. Simple enough.

However, to generate the corresponding server and client code for these service definitions, you need to use the appropriate plugins during the compilation process.

For example, in Go, the protoc compiler requires the --go-grpc_out=. flag to generate the gRPC-specific code from your service definitions. Without this flag (or the equivalent plugin for your target language), the service definitions in your .proto file will not produce any service-related code during the code generation process.

Extensions & Any

#

Picture this—you’re working on a large system with multiple teams contributing different features, but everyone’s relying on the same core messages. Updating those core messages directly can get messy. Every change risks breaking something for other teams, and constantly tweaking the original .proto files just isn’t practical.

Extensions let you add new fields to an existing message without changing the original definition:

// monitoring/metrics.proto

package monitoring;

message MetricData {

string service_name = 1;

string metric_name = 2;

double value = 3;

extensions 100 to 199;

}

Here, you’ve got your core MetricData message with some basic fields. You’re also reserving space for future extensions—fields from 100 to 199.

Let’s say another team wants to track error codes and detailed logs for their monitoring events. Instead of changing the original message, they can extend it:

// monitoring/extended_metrics.proto

import "monitoring/metrics.proto";

package monitoring.extensions;

extend monitoring.MetricData {

optional int32 error_code = 100;

repeated string logs = 101;

}

That team can safely add new fields without interfering with other teams or the core message structure. Once those tag numbers (100 and 101) are used, they’re off-limits for other extensions.

However, to help manage which numbers are already in use, you can declare them directly in the core message:

message MetricData {

string service_name = 1;

string metric_name = 2;

double value = 3;

extensions 100 to 199 [

declaration = {

number: 100,

full_name: ".monitoring.extensions.error_code",

type: "int32"

},

declaration = {

number: 101,

full_name: ".monitoring.extensions.logs",

type: "string",

repeated: true

}

];

}

Note that extensions are only supported in proto2 and edition 2023. In proto3, extensions were replaced by the Any type, which allows for adding dynamic data.

Any

#

Protobuf introduced the Any type to solve the same problem as extensions—but in a much simpler way. Instead of reserving field numbers ahead of time and defining extensions separately, Any lets you attach any message directly inside another message:

import "google/protobuf/any.proto";

message MonitoringEvent {

string event_id = 1;

string source = 2;

google.protobuf.Any payload = 3;

}

Here, the payload field can hold any message type. This gives teams the flexibility to define their own structures. For instance, let’s say the metrics team wants to include their own payload in metrics.proto:

package metrics;

message MetricsPayload {

string metric_name = 1;

double value = 2;

}

At the same time, the logs team could define their own payload like this:

package logs;

message LogPayload {

string timestamp = 1;

string message = 2;

}

In Go, to use the Any type, you’ll rely on the google.golang.org/protobuf/types/known/anypb package. Here’s how you can wrap a message into an Any type:

func main() {

metricsPayload, _ := anypb.New(&MetricsPayload{

MetricName: "test",

Value: 123,

})

p := &MonitoringEvent{

EventId: "123",

Source: "test",

Payload: metricsPayload,

}

}

Later, when you receive a message and need to figure out what’s inside the payload, you can check its type using the MessageIs function. This helps confirm whether the payload contains a specific message type:

metricsPayload2 := &MetricsPayload{}

if p.Payload.MessageIs(metricsPayload2) {

fmt.Println("It's indeed a MetricsPayload")

}

Versions

#

So far, there have been three public versions of Protobuf, each bringing its own set of changes:

proto2: The first major release that set the foundation.proto3: It broke quite a few things from proto2. It removed custom default values, made optional fields implicit by default, and expanded support for more programming languages, etc.edition 2023: The latest version, and instead of usingsyntax = "proto2"orsyntax = "proto3"at the top of your.protofiles, you now writeedition = "2023". The idea here is to let the language evolve more smoothly over time—without needing a major overhaul every time a new feature is added.

The newest version, edition 2023, brings a sense of balance between the older versions. It reintroduces features that were dropped in proto3, like extensions, explicit default values ([default = value]), clear field presence tracking, and so on.

Now, let’s talk about field presence—which basically refers to whether a field in your message has been set or not. A field can be in one of three states:

- Assign it a value: it’s set and holds that value.

- Assign it an empty value: it’s still set but holds a zero value.

- Don’t assign anything: it’s not present at all, and it’s also not equal to the default value.

Different versions of Protobuf handle this differently. In proto2, explicit field presence was the default. You could clearly tell the difference between a field that wasn’t set (nil/null) and one that was set but empty.

But with proto3, things changed. Presence became implicit by default—meaning there was no way to distinguish between an unset field and a field set with an empty value. When serialized, any field with a zero value will be omitted from the binary output. After a while, proto3 introduced the optional keyword to make field presence explicit again.

In edition 2023, explicit presence is back as the default behavior. This gives you better control over whether a field has been set—but it’s also a breaking change for generated code.

For example, a regular string field in proto3 would just be a string. But with edition 2023, that same field would become a *string in Go, so you can track whether it’s set or left untouched.

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem. If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus