- Blog /

- From net/rpc to gRPC in Go Applications

From net/rpc to gRPC in Go Applications

This article kicks off a series on communication protocols related to gRPC:

- From net/rpc to gRPC in Go Applications (We’re here)

- How HTTP/2 Works and How to Enable It in Go

- Practical Protobuf - From Basic to Best Practices

- How Protobuf Works—The Art of Data Encoding

- gRPC in Go: Streaming RPCs, Interceptors, and Metadata

To start things off, we’re keeping it simple: cover the basics of gRPC and Protobuf, and then build an RPC setup (not gRPC yet, gRPC is just typical way to implement RPC). We’ll use Go’s built-in net/rpc package to get a feel for how it all works under the hood and why we need gRPC.

What’s gRPC & Protobuf?

#

In a nutshell, gRPC (Google Remote Procedure Call) is a way to get different services talking to each other faster and more efficiently. The catch is, it’s a bit less straightforward than your usual REST setup.

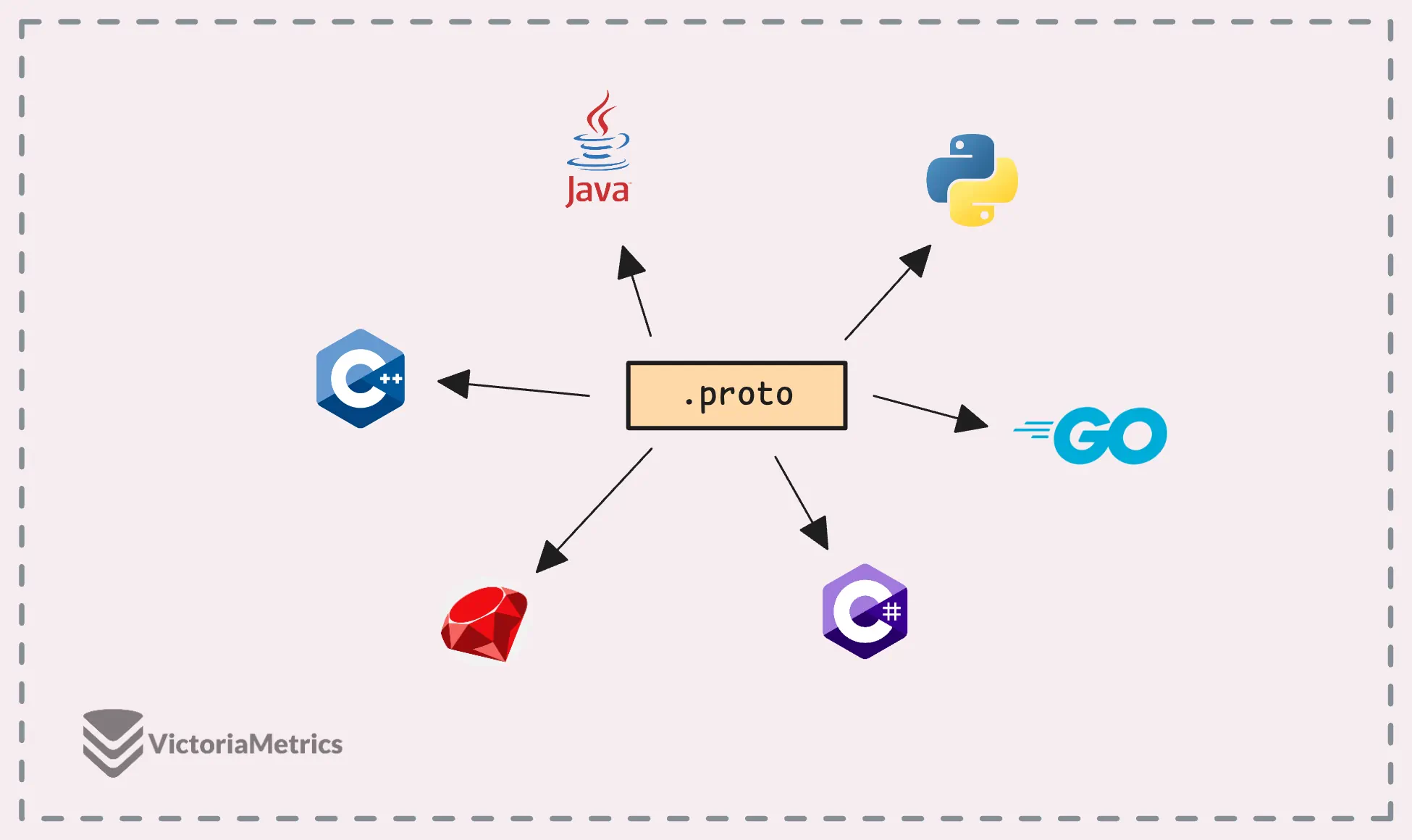

With JSON-based APIs, you’d define your API contracts in a document like Swagger. But gRPC takes a different strategy. Everything starts with .proto files — these are your blueprints for how services communicate. They define the types of data, the fields, and the rules for exchanging messages. From this file, gRPC can generate client and server code for you, so you don’t have to write it from scratch.

Here’s an example of a simple .proto file. It defines a user service and the messages that let services talk to each other using Protobuf (Protocol Buffers):

syntax = "proto3"; // Using the latest Protobuf version

package example.app; // Namespace for generated code

// Import another .proto file

import "google/protobuf/timestamp.proto";

// Enum

enum UserRole {

USER = 0;

ADMIN = 1;

SUPER_ADMIN = 2;

}

// Message for a user

message User {

int32 id = 1;

string name = 2;

optional string email = 3;

UserRole role = 4;

google.protobuf.Timestamp created_at = 5;

}

message GetUserRequest {

int32 user_id = 1;

}

message GetUserResponse {

User user = 1;

}

// Service definition

service UserService {

rpc GetUser (GetUserRequest) returns (GetUserResponse); // Fetch a single user

rpc CreateUser (User) returns (GetUserResponse); // Create a new user

}

That’s a lot to unpack, but don’t worry — it’s mostly just Protobuf syntax: things like imports, enums, messages, services, and rpcs. Once you’ve seen it a few times, it starts to click. We’ll revisit this section later on.

gRPC uses HTTP/2 as its underlying protocol and it makes it easier to send concurrent requests over a single connection.

“Why?”

With HTTP/1.1, your browser typically opens multiple “phone lines” (TCP connections) to handle several requests at once, like fetching images, text, code from a webpage. Otherwise, it processes them one by one. HTTP/2 changes the game by using a single connection to send all the requests simultaneously and this clever trick is called “multiplexing.”

Now, what make it feel different to your normal REST is, you don’t think in terms of “endpoints” anymore.

Instead, you’re calling functions on the server like they’re part of your own code. That’s what Remote Procedure Call (RPC) is all about. The server does all the heavy lifting behind the scenes, but to you, it just feels like calling a regular function.

“Okay, but why not use gRPC for everything?”

It’s all about trade-offs. gRPC brings speed, consistency, and a robust typing system to the table, but it doesn’t have the same simplicity or flexibility as JSON-based APIs.

- Go with gRPC: If you care about performance, low latency, real-time communication, or need something that works well across different languages (e.g., Python, Java, C++).

- Stick with REST: If you value simplicity, easy to read, easy to write, and flexibility (like avoiding client updates every time your API changes), or you’re building something browser-based.

And that’s it for now! We’re not jumping straight into gRPC, HTTP/2, or Protobuf just yet. Instead, we’ll start from the ground up with Go’s net/rpc package to build a solid foundation.

net/rpc

#

First off, a little heads-up, net/rpc isn’t the same as gRPC. It uses its own custom binary protocol over HTTP or raw TCP, and it doesn’t have the fancy features or performance benefits of HTTP/2. That said, it’s part of Go’s standard library, which makes it a simple way to demonstrate the idea of RPC in action.

Let’s not overcomplicate it. Here’s a quick example to get the gist of how it works:

// Service is the struct defining the service.

type Service struct{}

// Hello is the method exposed to RPC clients.

func (h *Service) Hello(request string, reply *string) error {

*reply = "Hello, " + request + "!"

return nil

}

func main() {

_ = rpc.Register(new(Service))

listener, _ := net.Listen("tcp", ":8080")

defer listener.Close()

// Accept connections and serve them in separate goroutines.

for {

conn, _ := listener.Accept()

go rpc.ServeConn(conn)

}

}

Skipping error handling here to keep things focused.

This snippet sets up the server side. It listens on port 8080 for TCP connections and serves the Service through the net/rpc package. A few things to keep in mind about the service and its methods:

- The service’s type has to be exported.

- The method must also be exported.

- Methods need exactly two arguments: the first is a value type (input), and the second is a pointer (output), which lets the server write back the result to the client.

- The method can only return one value, and that’s an error. Any actual data goes back to the client through the second argument.

So, the signature of a valid RPC method looks like this:

func (t *Type) MethodName(argType Argument, replyType *Reply) error

And, RPC is about sending data, things like function arguments or return values, between a client and a server. For this to work, the data has to be encoded into a format that can travel over the network, and then decoded on the other side. With net/rpc, this encoding and decoding happens automatically using the gob format by default.

“What’s with the

gobformat?”

gob is Go’s native way of serializing data. It takes Go data structures and turns them into a compact binary format that’s easy to send over a network or save to a file. The catch is, it’s Go-centric, so it’s perfect if both the client and server are written in Go but not great if you’re mixing languages.

Now let’s see how you’d create a client to call the Hello method from the Service:

func main() {

// Connect to the server at localhost:8080.

client, _ := rpc.Dial("tcp", "localhost:8080")

defer client.Close()

// Make a remote call to the Service.Hello method.

var reply string

_ = client.Call("Service.Hello", "World", &reply)

fmt.Println(reply)

}

// Output:

// Hello, World!

Here’s the play-by-play of what’s happening:

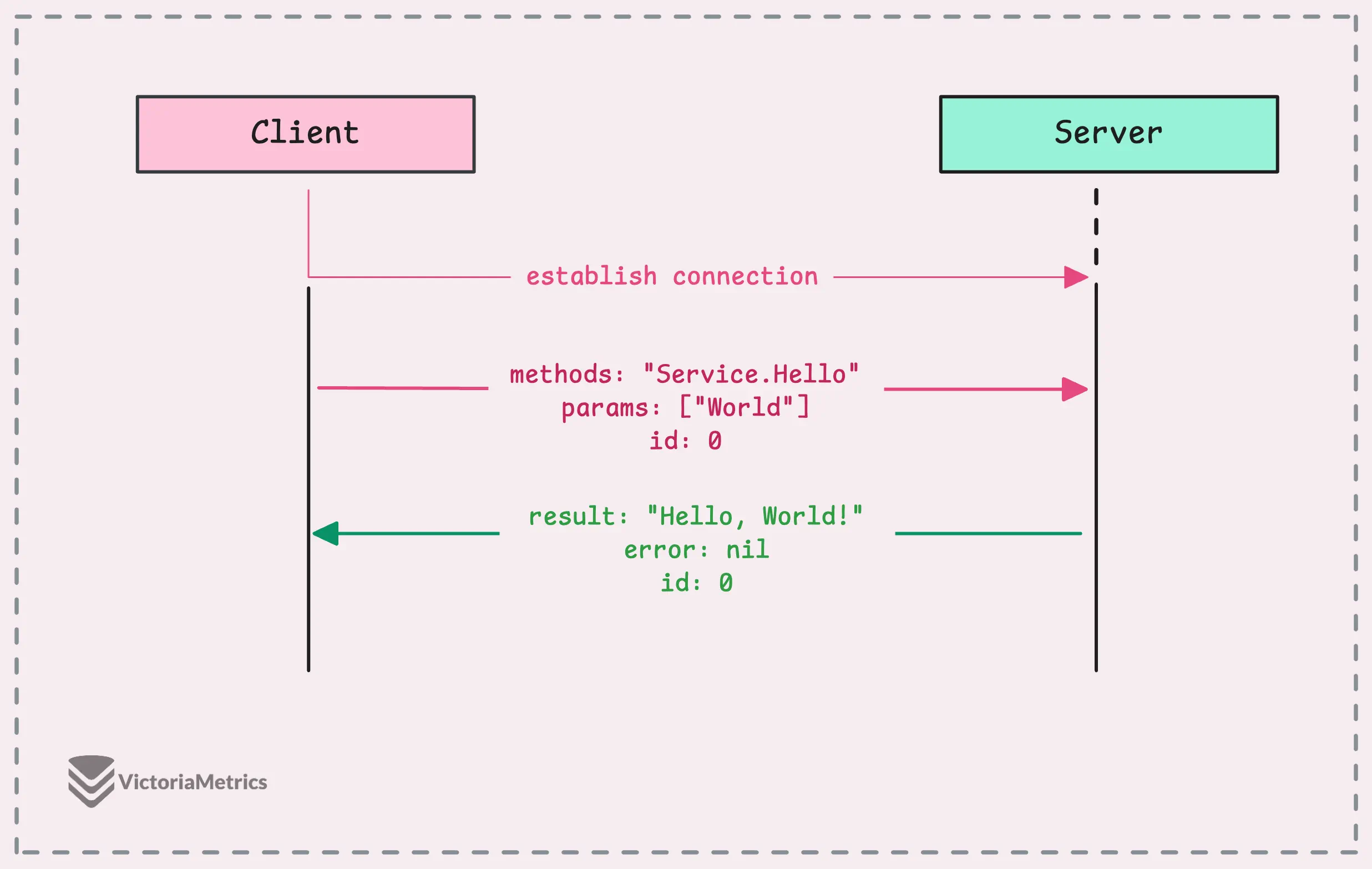

The client starts by dialing the server. This is where the TCP handshake happens (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK, you get the idea). The rpc.Dial function you see here is just Go’s net.Dial under the hood, so no magic.

Next, the client creates a request. This request includes: the name of the service (Service), the name of the method (Hello), and the arguments you’re passing in ("World"). Everything is then packed up into a neat binary format using gob. Along with that, the request gets a sequence number, an incremental number that starts at zero and goes up with each request.

“Why does it need a sequence number?”

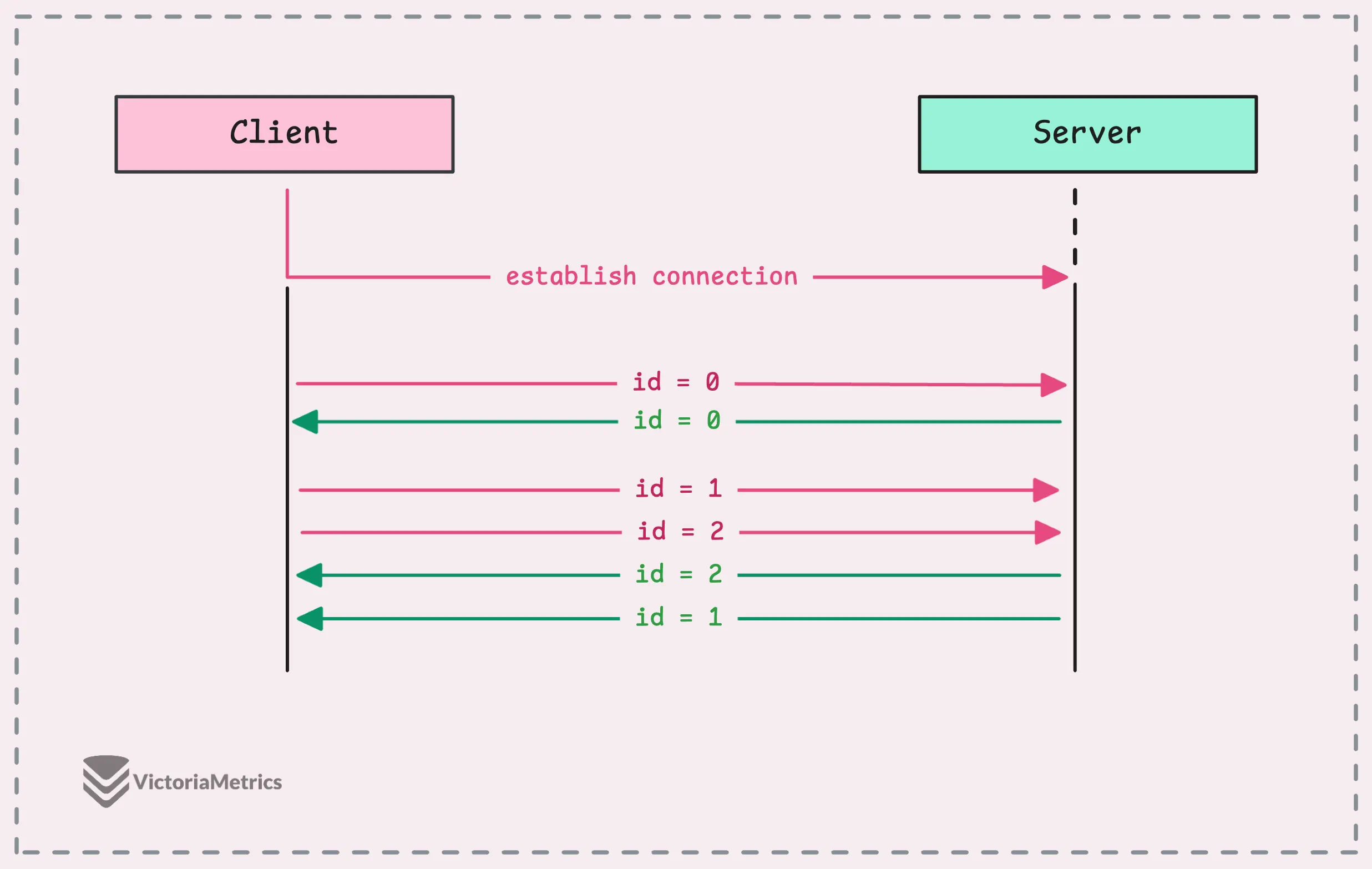

It’s all about keeping things organized. Let’s talk about that connection.

When the client connects to the server, they set up a single TCP connection. This connection stays open until you explicitly close it or something goes wrong (like the server shutting down or the network breaking). And you can send multiple requests over that same connection without starting over. No need to keep shaking hands for every call.

You can even fire off several RPC requests at once, one after the other, or in parallel. The responses might come back in any order, depending on how quickly the server processes them. The sequence number ensures that each response lines up perfectly with its matching request.

On the server side, when a request comes in, the server decodes it to figure out which service and method it’s targeting. It checks its registry of services (remember, we registered the Service earlier) and spawns a goroutine to handle the call. That’s how it all ties together, requests, responses, and that sequence number keeping everything in sync.

“Does it use reflection? We didn’t explicitly provide methods for the server, how does it know?”

Yes, reflection does a lot of the heavy lifting here. It’s used at multiple stages: when the service is registered to figure out which methods are available; during request handling to create the right argument types; and finally, when it’s time to actually call the method. This heavy use of reflection is one reason why gRPC, with its pre-generated code, can be more performant than net/rpc.

Once the method finishes running and we’ve got a result, the server encodes both the result and any potential error using the codec (again, default is gob) and sends it back to the client over the same connection.

Back on the client side, the response arrives and is decoded. That sequence number we talked about earlier makes sure the response is matched to the right request. For synchronous calls (like client.Call), the result or error is handed right back to the caller. If it’s an asynchronous call (client.Go), the result goes through a channel.

“Okay, but

gobonly works with Go services. What if I want to connect to something written in another language?”

Great point. gob is definitely Go-specific, which is fine if your whole system is in Go, but not so helpful if you need to communicate across languages. Luckily, net/rpc supports swapping out the codec, and it even comes with built-in support for a JSON-based codec:

// Server

go rpc.ServeCodec(jsonrpc.NewServerCodec(conn))

// Client

conn, _ := net.Dial("tcp", "localhost:8080")

defer conn.Close()

client := rpc.NewClientWithCodec(jsonrpc.NewClientCodec(conn))

Instead of using rpc.ServeConn, we switch to rpc.ServeCodec, which lets us specify a custom codec. In this case, it’s JSON. Now if you log the request and response, it’s way more human-friendly. The request might look like this:

{ "method": "Service.Hello", "params": ["World"], "id": 0 }

And the response from server:

{ "id": 0, "result": "Hello, World!", "error": null }

If there’s an error, like calling a method that doesn’t exist, you’d see something like:

{

"id": 0,

"result": null,

"error": "rpc: can't find service Service.HelloFake"

}

It’s worth mentioning that net/rpc is considered “frozen.” This means it’s stable and works fine for basic use, but it’s not actively developed anymore. For modern apps, gRPC is often the better choice — it offers more features, supports multiple languages out of the box, and comes with advanced performance perks.

And that’s a wrap for now! If you’re curious about more common gRPC use cases, we’ll look into that in the next articles.

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem. If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus