- Blog /

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

If you’re new to Go, it can be a bit confusing to figure out how to use maps in Go. And even when you’re more experienced, understanding how maps really work can be pretty tough.

Take this example: Have you ever set a ‘hint’ for a map and wondered why it’s called a ‘hint’ and not something simple like length, like we do with slices?

// hint = 10

m := make(map[string]int, 10)

Or maybe you’ve noticed that when you use a for-range loop on a map, the order doesn’t match the insertion order, and it even changes if you loop over the same map at different times. But weirdly enough, if you loop over it at the exact same time, the order usually stays the same.

This is a long story, so fasten your seat belt and dive in.

Before we move on, just a heads up—the info here is based on Go 1.23. If things have changed and this isn’t up to date, feel free to ping me on X(@func25).

Map in Go: Quick Start

#

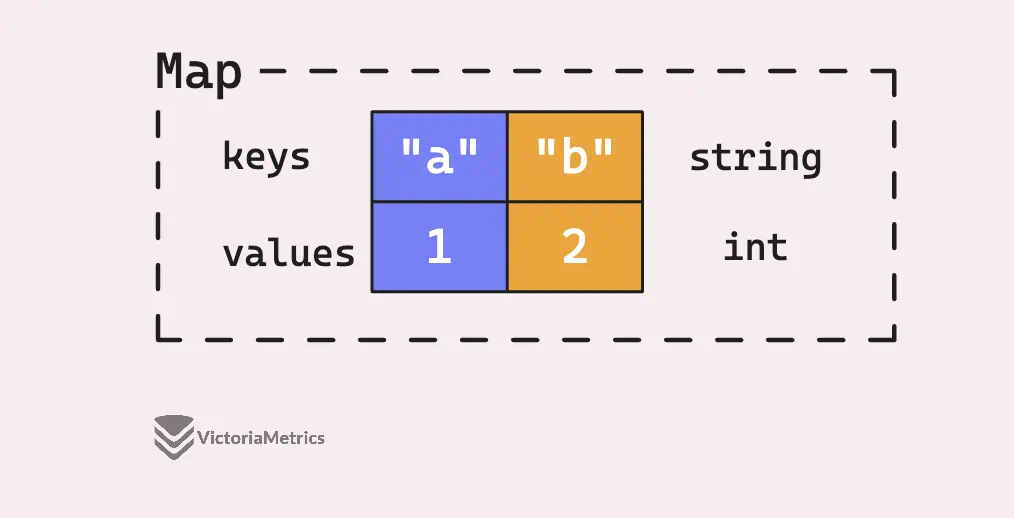

So, let’s talk about maps in Go, it’s a built-in type that acts as a key-value storage. Unlike arrays where you’re stuck with keys as increasing indices like 0, 1, 2, and so on, with maps, the key can be any comparable type.

That gives you a lot more flexibility.

m := make(map[string]int)

m["a"] = 1

m["b"] = 2

m // map[a:1 b:2]

In that example, we created an empty map using make(), where the keys are strings and the values are ints.

Now, instead of manually assigning each key, you can save yourself some time by using a map literal. This lets you set up your key-value pairs all at once, right when you create the map:

m := map[string]int{

"a": 1,

"b": 2,

}

All you do is list out the keys and their values inside curly braces when you first create the map, simple as that.

And if you realize later that you don’t need a certain key-value pair anymore, Go’s got you covered. There’s a handy delete function that, well, deletes the key you don’t want: delete(m, "a").

The zero value of a map is nil, and a nil map is kind of like an empty map in some ways. You can try to look up keys in it, and Go won’t freak out and crash your program.

If you search for a key that isn’t there, Go just quietly gives you the “zero value” for that map’s value type:

var m map[string]int

println(m["a"]) // 0

m["a"] = 1 // panic: assignment to entry in nil map

But here’s the thing: you can’t add new key-value pairs to a nil map.

In fact, Go handles maps in a way that’s pretty similar to how it deals with slices. Both maps and slices start off as nil, and Go doesn’t panic if you do something “harmless” with them while they’re nil. For example, you can loop over a nil slice without any “drama”.

So, what happens if you try to loop over a nil map?

var m map[string]int

for k, v := range m {

println(k, v)

}

Nothing happens, no errors, no surprises. It just quietly does nothing.

Go’s approach is to treat the default value of any type as something useful, not something that causes your program to blow up. The only time Go throws a fit is when you do something that’s truly illegal, like trying to add a new key-value pair to a nil map or accessing an out-of-bounds index in a slice.

There are a couple more things you should know about maps in Go:

- A for-range loop over a map won’t return the keys in any specific order.

- Maps aren’t thread-safe, the Go runtime will cause a fatal error if you try to read (or iterate with a for-range) and write to the same map simultaneously.

- You can check if a key is in a map by doing a simple

okcheck:_, ok := m[key]. - The key type for a map must be comparable.

Let’s dive into that last point about map keys. I mentioned earlier that “the key could be any comparable type,” but there’s a bit more to it than just that.

“So, what exactly is a comparable type? And what isn’t?”

It’s pretty simple: if you can use == to compare two values of the same type, then that type is considered comparable.

func main() {

var s map[int]string

if s == s {

println("comparable")

}

}

// compile error: invalid operation: s == s (map can only be compared to nil)

But as you can see, the code above doesn’t even compile. The compiler complains: “invalid operation: s == s (map can only be compared to nil).”

This same rule applies to other non-comparable types like slices, functions, or structs that contain slices or maps, etc. So, if you’re trying to use any of those types as keys in a map, you’re out of luck.

func main() {

var s map[[]int]string

}

// compile error: invalid map key type []intcompilerIncomparableMapKey

But here’s a little secret, interfaces can be both comparable and non-comparable.

What does that mean? You can absolutely define a map with an empty interface as the key without any compile errors. But watch out, there’s a good chance you’ll run into a runtime error.

func main() {

m := map[interface{}]int{

1: 1,

"a": 2,

}

m[[]int{1, 2, 3}] = 3

m[func() {}] = 4

}

// panic: runtime error: hash of unhashable type []int

// panic: runtime error: hash of unhashable type func()

Everything looks fine until you try to assign an uncomparable type as a map key.

That’s when you’ll hit a runtime error, which is trickier to deal with than a compile-time error. Because of this, it’s usually a good idea to avoid using interface{} as a map key unless you have a solid reason and constraints that prevent misuse.

But that error message: “hash of unhashable type []int” might seem a bit cryptic. What’s this about a hash? Well, that’s our cue to dig into how Go handles things under the hood.

Map Anatomy

#

When explaining the internals of something like a map, it’s easy to get bogged down in the nitty-gritty details of the Go source code. But we’re going to keep it light and simple so even those new to Go can follow along.

What you see as a single map in your Go code is actually an abstraction that hides the complex details of how the data is organized. In reality, a Go map is composed of many smaller units called “buckets.”

type hmap struct {

...

buckets unsafe.Pointer

...

}

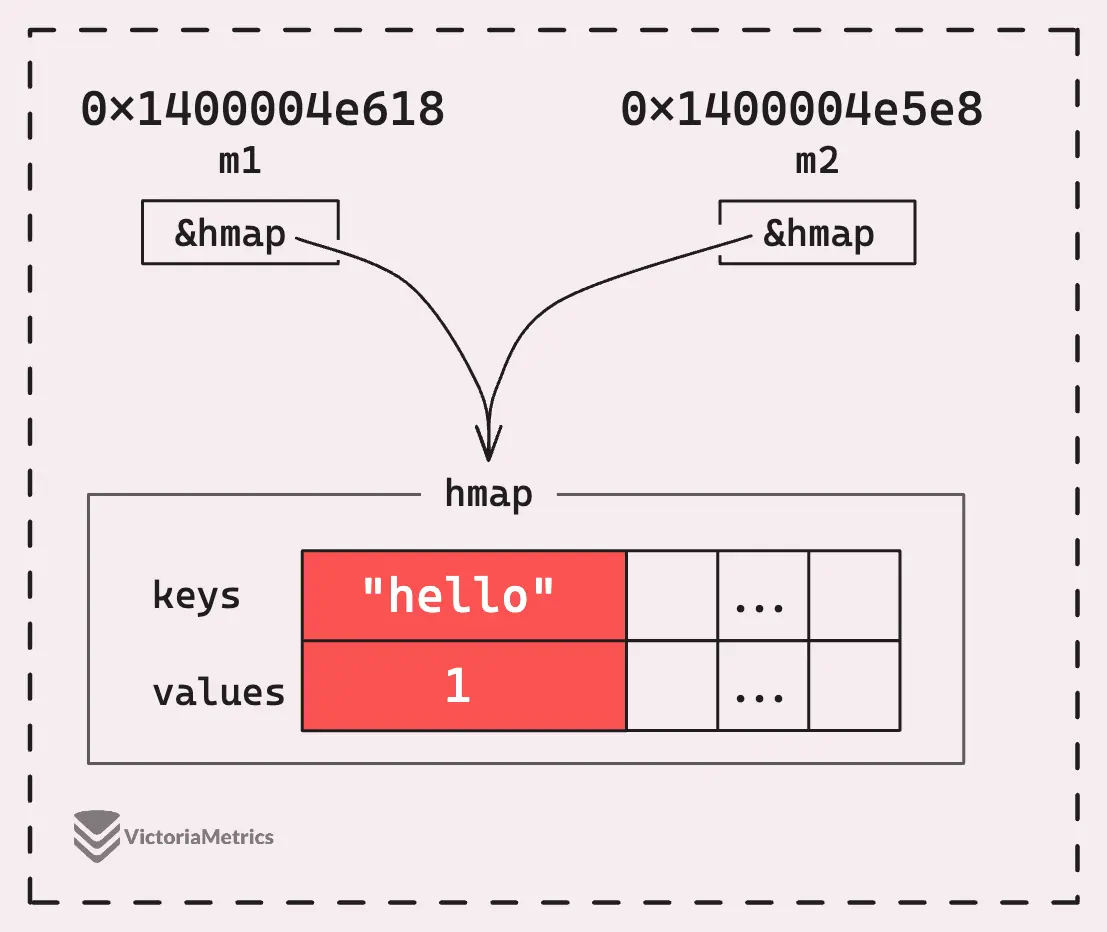

Look at Go source code above, a map contains a pointer that points to the bucket array.

This is why when you assign a map to a variable or pass it to a function, both the variable and the function’s argument are sharing the same map pointer.

func changeMap(m2 map[string]int) {

m2["hello"] = 2

}

func main() {

m1 := map[string]int{"hello": 1}

changeMap(m1)

println(m1["hello"]) // 2

}

But don’t get it twisted, maps are pointers to the hmap under the hood, but they aren’t reference types, nor are they passed by reference like a ref argument in C#, if you change the whole map m2, it won’t reflect on the original map m1 in the caller.

func changeMap(m2 map[string]int) {

m2 = map[string]int{"hello": 2}

}

func main() {

m1 := map[string]int{"hello": 1}

changeMap(m1)

println(m1["hello"]) // 1

}

In Go, everything is passed by value. What’s really happening is a bit different: when you pass the map m1 to the changeMap function, Go makes a copy of the *hmap structure. So, m1 in the main() and m2 in the changeMap() function are technically different pointers point to the same hmap.

For more on this topic, there’s a great post by Dave Cheney titled There is no pass-by-reference in Go.

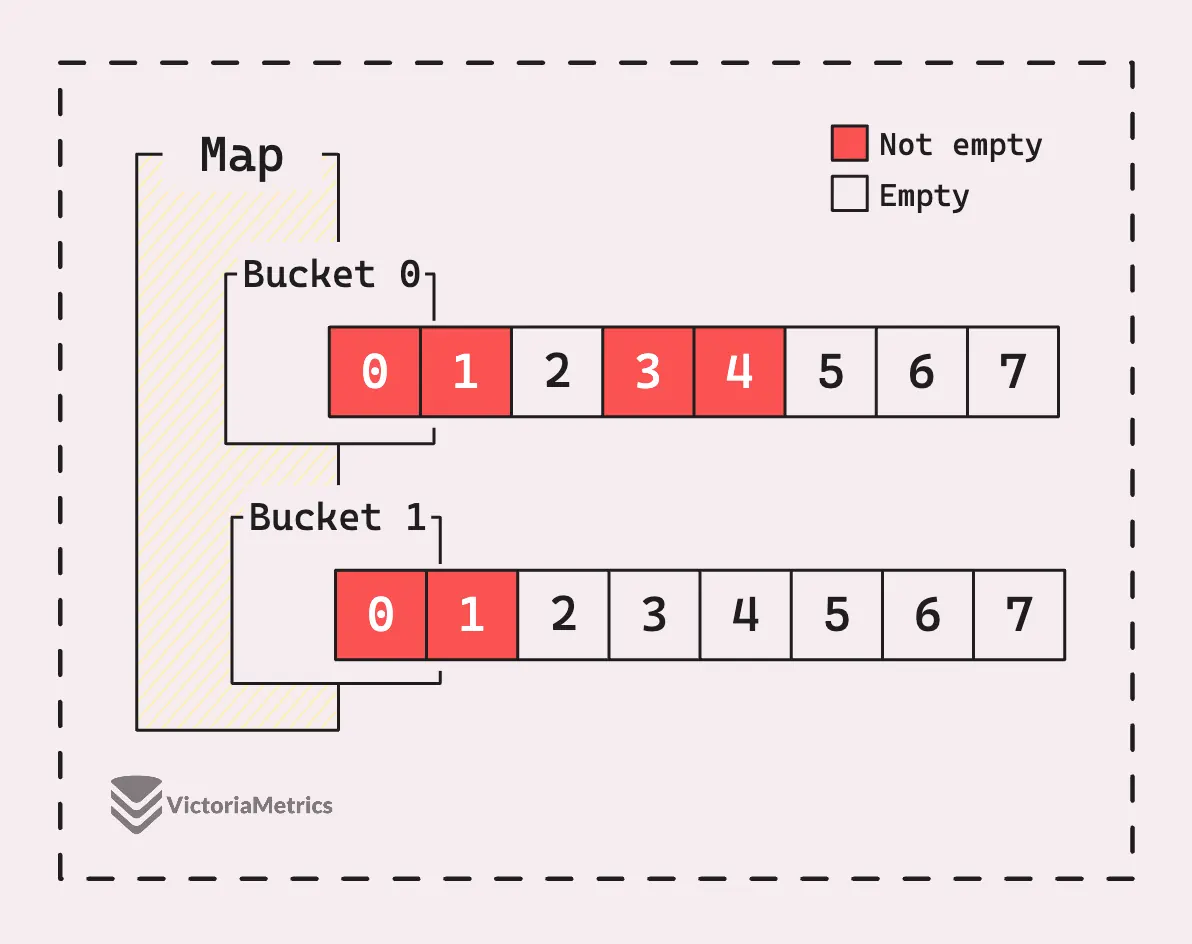

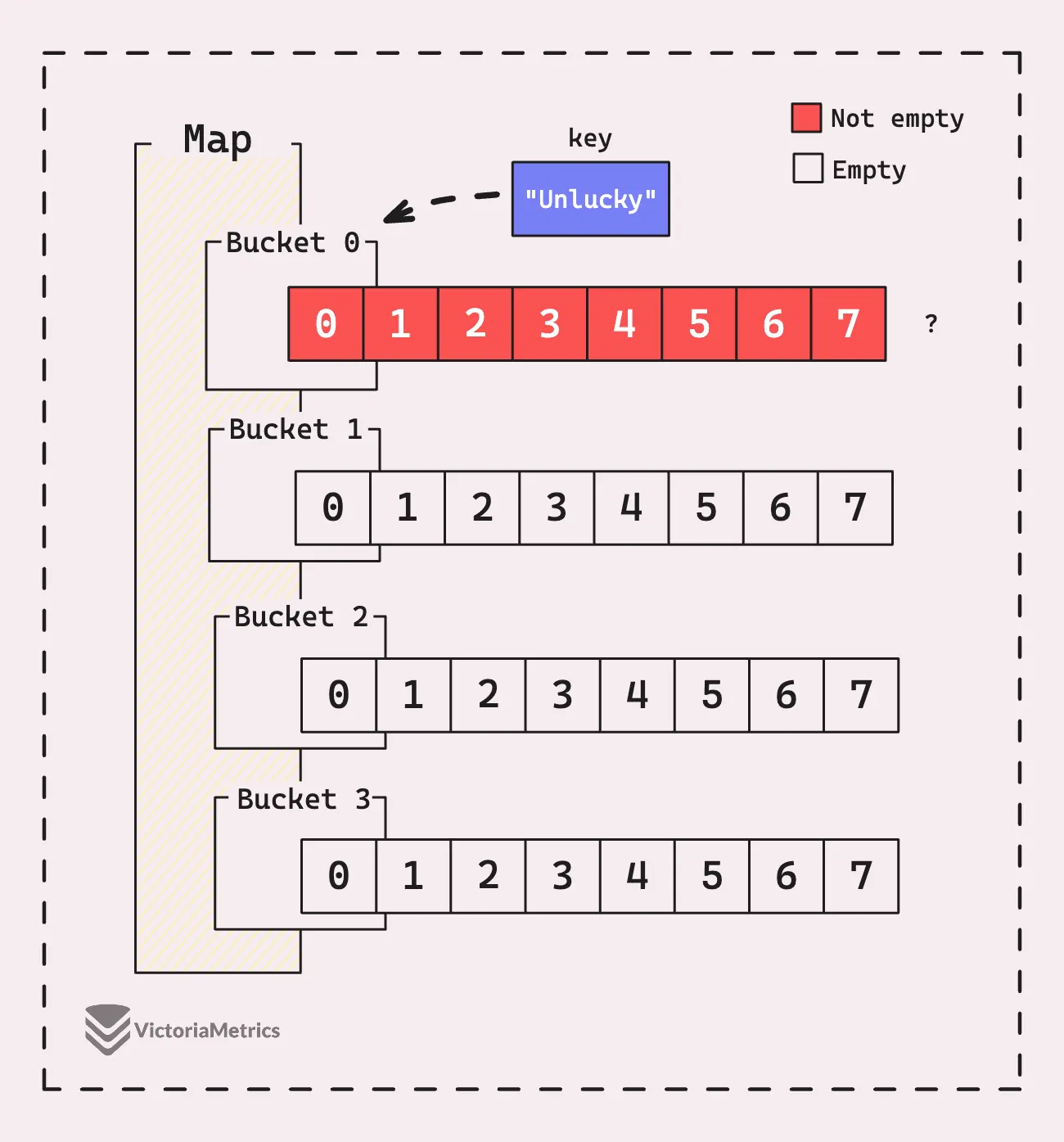

Each of these buckets can only hold up to 8 key-value pairs, as you can see in the image below.

The map above has 2 buckets, and len(map) is 6.

So, when you add a key-value pair to a map, Go doesn’t just drop it in there randomly or sequentially. Instead, it places the pair into one of these buckets based on the key’s hash value, which is determined by hash(key, seed).

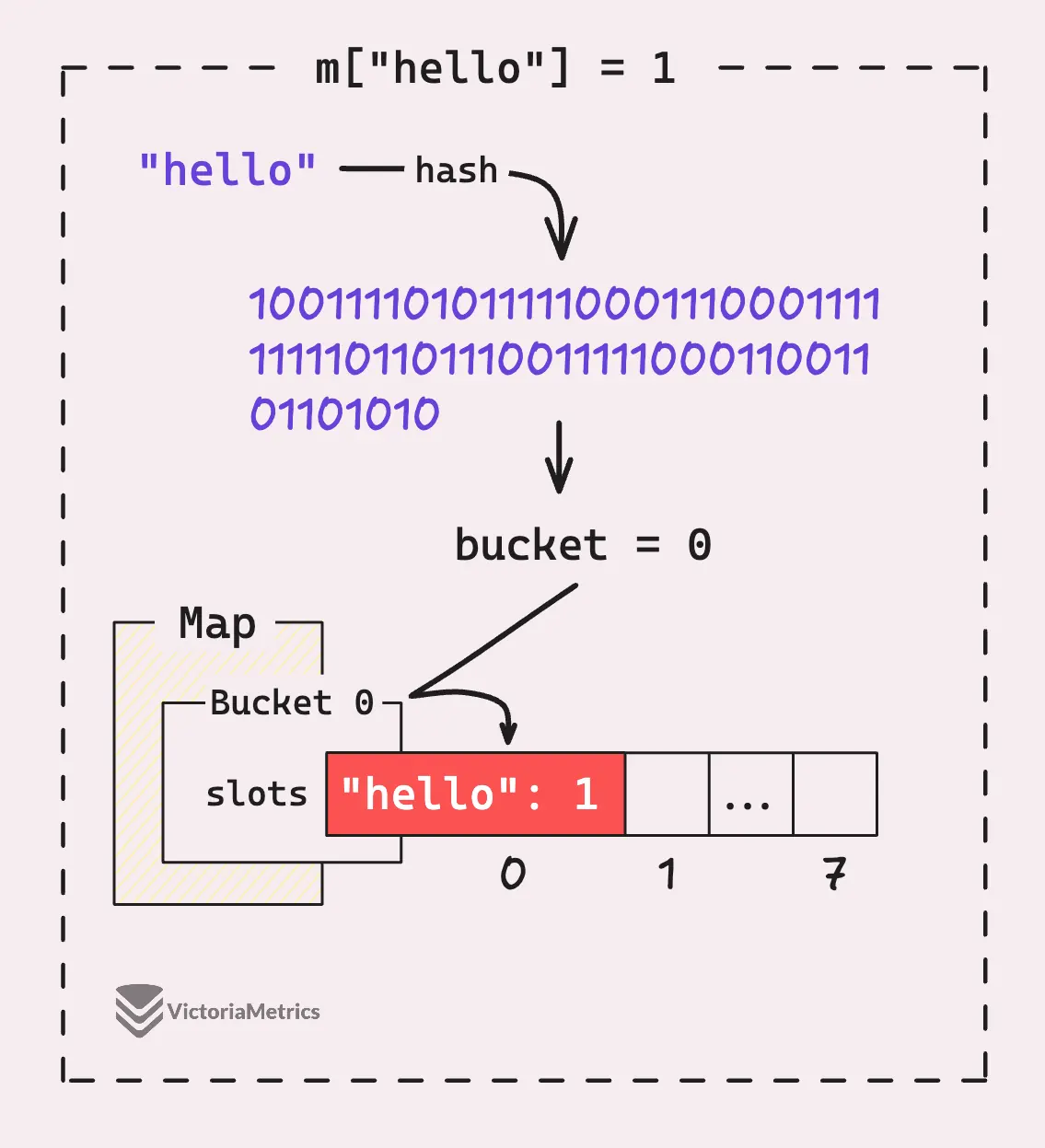

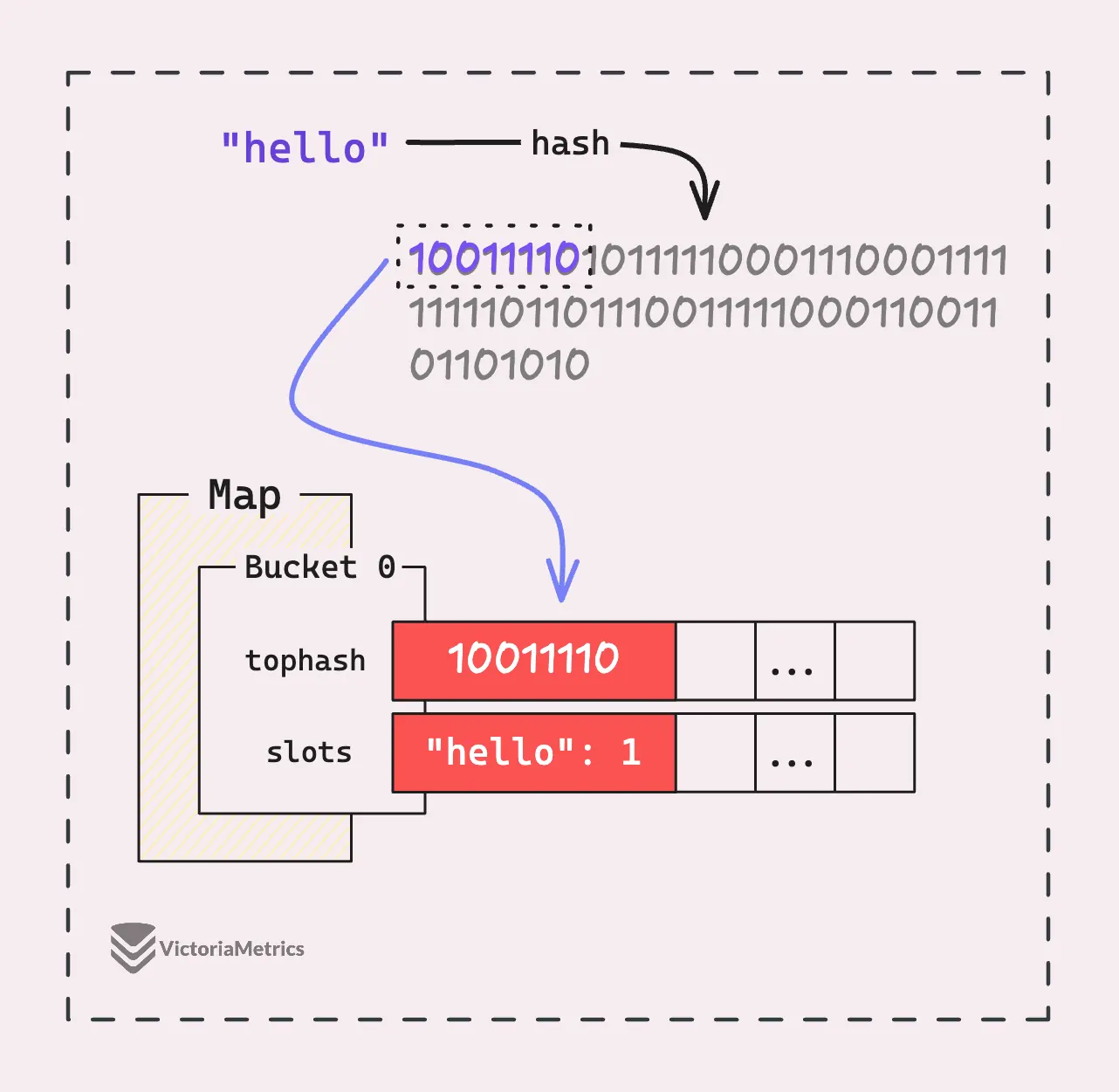

Let’s see the simplest assignment scenario in the image below, when we have an empty map, and assign a key-value pair "hello": 1 to it.

It starts by hashing “hello” to a number, then it takes that number and mods it by the number of buckets.

Since we only have one bucket here, any number mod 1 is 0, so it’s going straight into bucket 0 and the same process happens when you add another key-value pair. It’ll try to place it in bucket 0, and if the first slot’s taken or has a different key, it’ll move to the next slot in that bucket.

Take a look at the hash(key, seed), when you use a for-range loop over two maps with the same keys, you might notice that the keys come out in a different order:

func main() {

a := map[string]int{"a": 1, "b": 2, "c": 3, "d": 4, "e": 5, "f": 6}

b := map[string]int{"a": 1, "b": 2, "c": 3, "d": 4, "e": 5, "f": 6}

for i := range a {

print(i, " ")

}

println()

for i := range b {

print(i, " ")

}

}

// Output:

// a b c d e f

// c d e f a b

How’s that possible? Isn’t the key “a” in map a and the key “a” in map b hashed the same way?

But here’s the deal, while the hash function used for maps in Go is consistent across all maps with the same key type, the seed used by that hash function is different for each map instance. So, when you create a new map, Go generates a random seed just for that map.

In the example above, both a and b use the same hash function because their keys are string types, but each map has its own unique seed.

“Wait, a bucket has only 8 slots? What happens if the bucket gets full? Does it grow like a slice?”

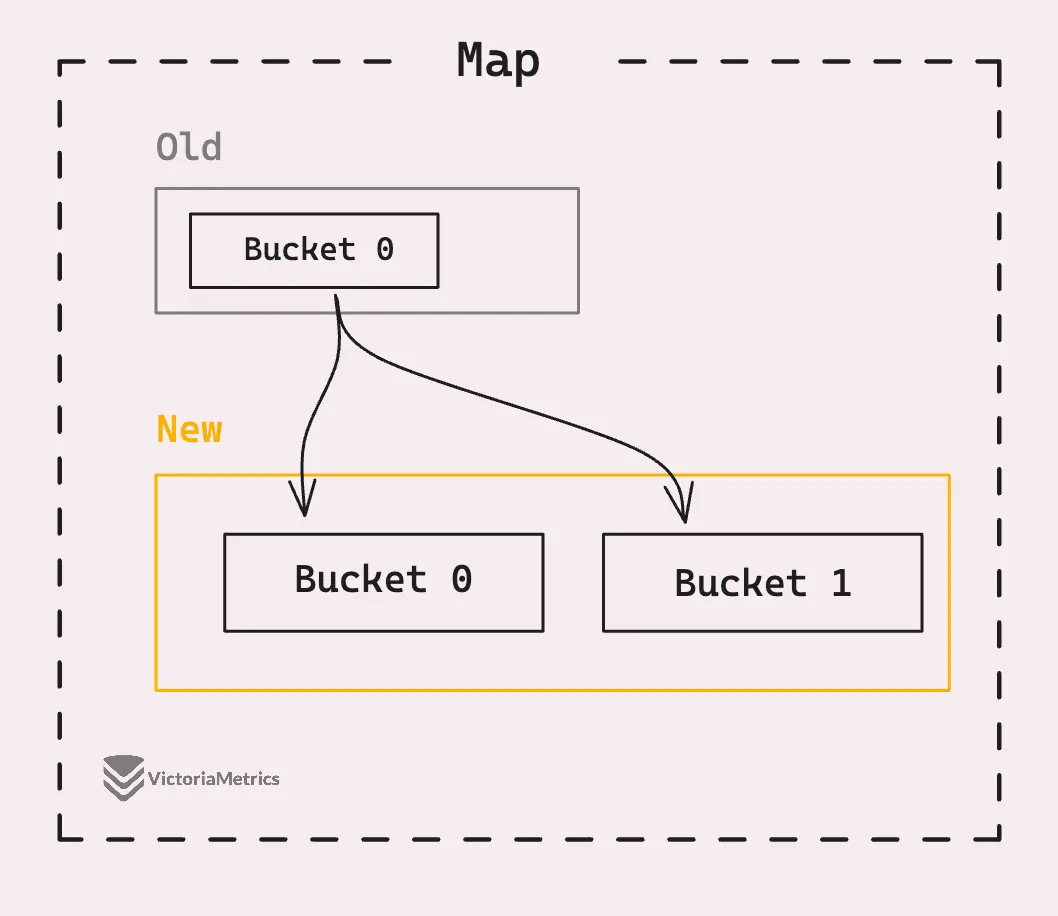

Well, sort of. When the buckets start getting full, or even almost full, depending on the algorithm’s definition of “full”, the map will trigger a growth, which might double the number of main buckets.

But here’s where it gets a bit more interesting.

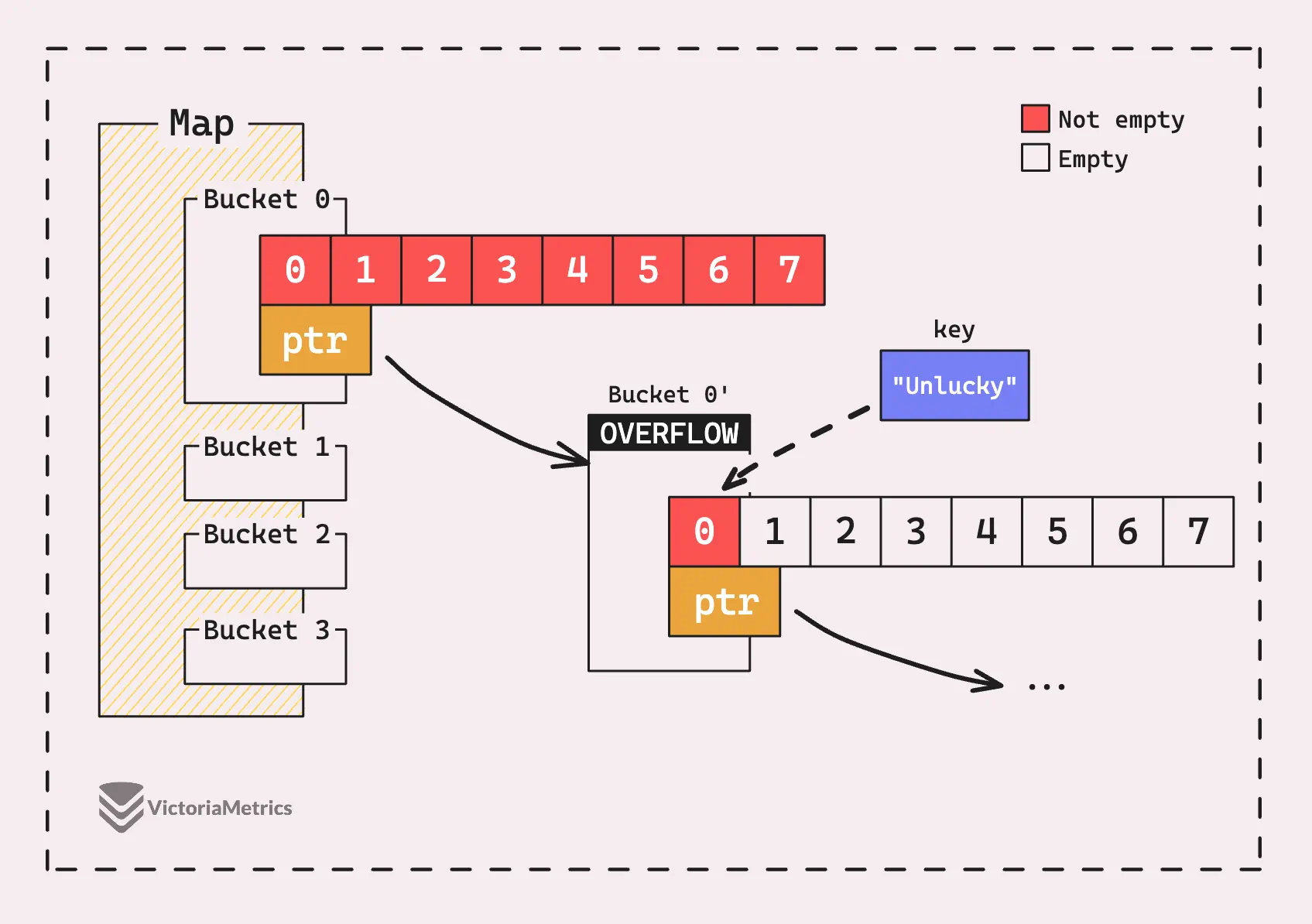

When I say “main buckets,” I’m setting up for another concept: “overflow buckets.” These come into play when you’ve got a situation with high collisions. Imagine you have 4 buckets, but one of them is completely filled with 8 key-value pairs due to high collisions, while the other 3 buckets are sitting empty.

Do you really need to grow the map to 8 buckets just because you need to add one more entry that, unfortunately, also lands in that first full bucket?

Absolutely not, right? It’d be pretty wasteful to double the number of buckets in that case.

Instead, Go handles this more efficiently by creating “overflow buckets” that are linked to the first bucket. The new key-value pair gets stored in this overflow bucket rather than forcing a full grow.

A map in Go grows when one of two conditions is met: either there are too many overflow buckets, or the map is overloaded, meaning the load factor is too high.

Because of these 2 conditions, there are also two kinds of growth:

- One that doubles the size of the buckets (when overloaded)

- One that keeps the same size but redistributes entries (when there are too many overflow buckets).

If there are too many overflow buckets, it’s better to redistribute the entries rather than just adding more memory.

Currently, Go’s load factor is set at 6.5, this means the map is designed to maintain an average of 6.5 items per bucket, which is around 80% capacity. When the load factor goes beyond this threshold, the map is considered overloaded. In this case, it will grow by allocating a new array of buckets that’s twice the size of the current one, and then rehashing the elements into these new buckets.

The reason we need to grow the map even when a bucket is just almost full comes down to performance. We usually think that accessing and assigning values in a map is O(1), right? But it’s not always that simple.

The more slots in a bucket that are occupied, the slower things get.

When you want to add another key-value pair, it’s not just about checking if a bucket has space, it’s about comparing the key with each existing key in that bucket to decide if you’re adding a new entry or updating an existing one.

And it gets even worse when you have overflow buckets, because then you have to check each slot in those overflow buckets too. This slowdown affects access and delete operations as well.

But Go team got your back, they optimized this comparison for us.

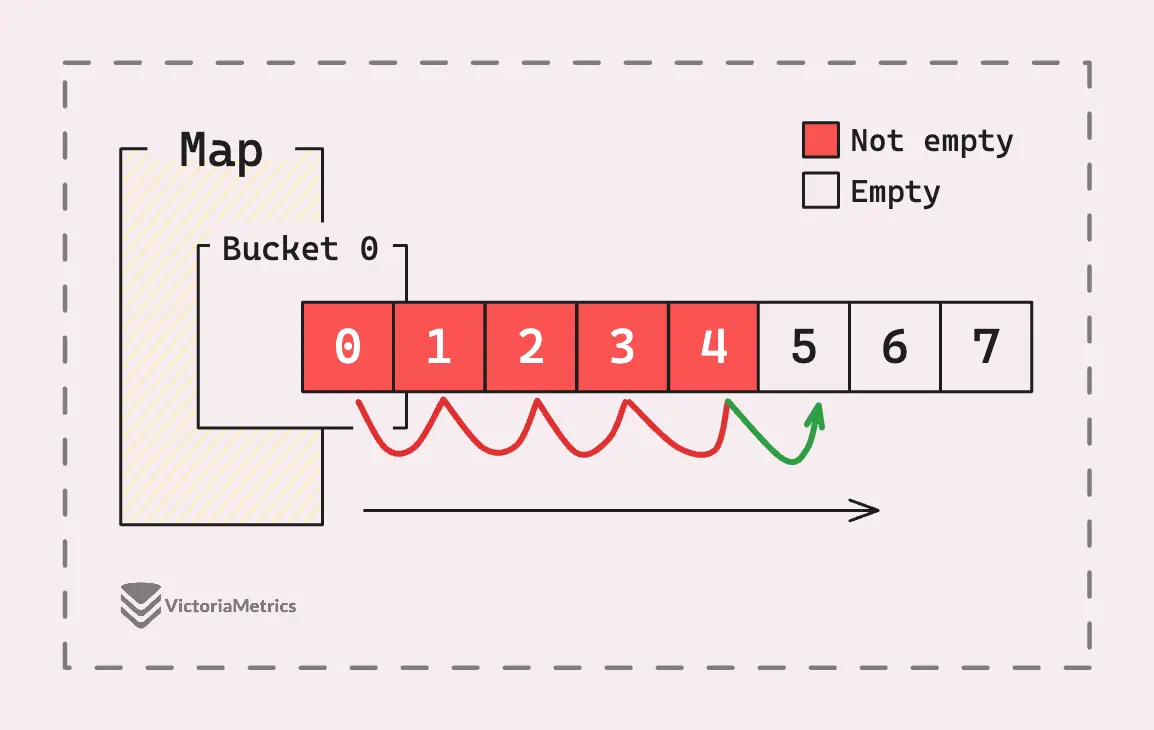

Remember the hash we got when hashing the key “Hello”? Go doesn’t just toss that away. It actually caches the tophash of “Hello” in the bucket as a uint8, and uses that for a quick comparison with the tophash of any new key. This makes the initial check super fast.

After comparing the tophash, if they match, it means the keys “might” be the same. Then, Go moves on to the slower process of checking whether the keys are actually identical.

“Why does creating a new map with make(map, hint) not provide an exact size but just a hint?”

By now, you’re probably in a good spot to answer this one. The hint parameter in make(map, hint) tells Go the initial number of elements you expect the map to hold.

This hint helps minimize the number of times the map needs to grow as you add elements.

Since each growth operation involves allocating a new array of buckets and copying existing elements over, it’s not the most efficient process. Starting with a larger initial capacity can help avoid some of these costly growth operations.

Let me give you a real-world look at how the bucket size grows as you add more elements:

| Hint Range | Bucket Count | Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 8 | 1 | 8 |

| 9 - 13 | 2 | 16 |

| 14 - 26 | 4 | 32 |

| 27 - 52 | 8 | 64 |

| 53 - 104 | 16 | 128 |

| 105 - 208 | 32 | 256 |

| 209 - 416 | 64 | 512 |

| 417 - 832 | 128 | 1024 |

| 833 - 1664 | 256 | 2048 |

“Why does a hint of 14 result in 4 buckets? We only need 2 buckets to cover 14 entries.”

This is where the load factor comes into play, remember that load factor threshold of 6.5? It directly influences when the map needs to grow.

- At hint 13, we have 2 buckets and that gives a load factor of 13/2 = 6.5, which hits the threshold but doesn’t exceed it. So, when you bump up to hint 14, the load factor would exceed 6.5, triggering the need to grow.

- The same goes for hint 26. With 4 buckets, the load factor is 26/4 = 6.5, again hitting that threshold. When you move beyond 26, the map needs to grow to accommodate more elements efficiently.

Basically, from the second range, you can see that the hint range doubles compared to the previous one, as do the bucket count and capacity.

Evacuation When Growing

#

As we talked about earlier, evacuation doesn’t always mean doubling the size of the buckets. If there are too many overflow buckets, evacuation will still happen, but the new bucket array will be the same size as the old one.

The more interesting scenario is when the bucket size doubles, so let’s focus on that.

Map growth answers two common questions: “Why can’t you get the address of a map’s element?” and “Why isn’t the for-range order guaranteed at different times?”

func main() {

a := map[string]int{"a": 1}

ptr := &a["a"]

}

// compiler error: invalid operation: cannot

// take address of a["a"] (map index expression of type int)

When a map grows, it allocates a new bucket array that’s double the size of the old one. All the entry positions in the old buckets become invalid, and they need to be moved to the new buckets with new memory addresses.

And the thing is, if your map has, say, 1000 key-value pairs, moving all those keys at once would be a pretty expensive operation, potentially blocking your goroutine for a noticeable chunk of time. To avoid that, Go uses “incremental growth,” where only a portion of the elements are rehashed at a time.

This way, the process is spread out, and your program keeps running smoothly without sudden lagging.

The process gets a bit more complex because we need to maintain the map’s integrity while reading, writing, deleting, or iterating, all while managing both the old and new buckets.

“When does incremental growth happen?”

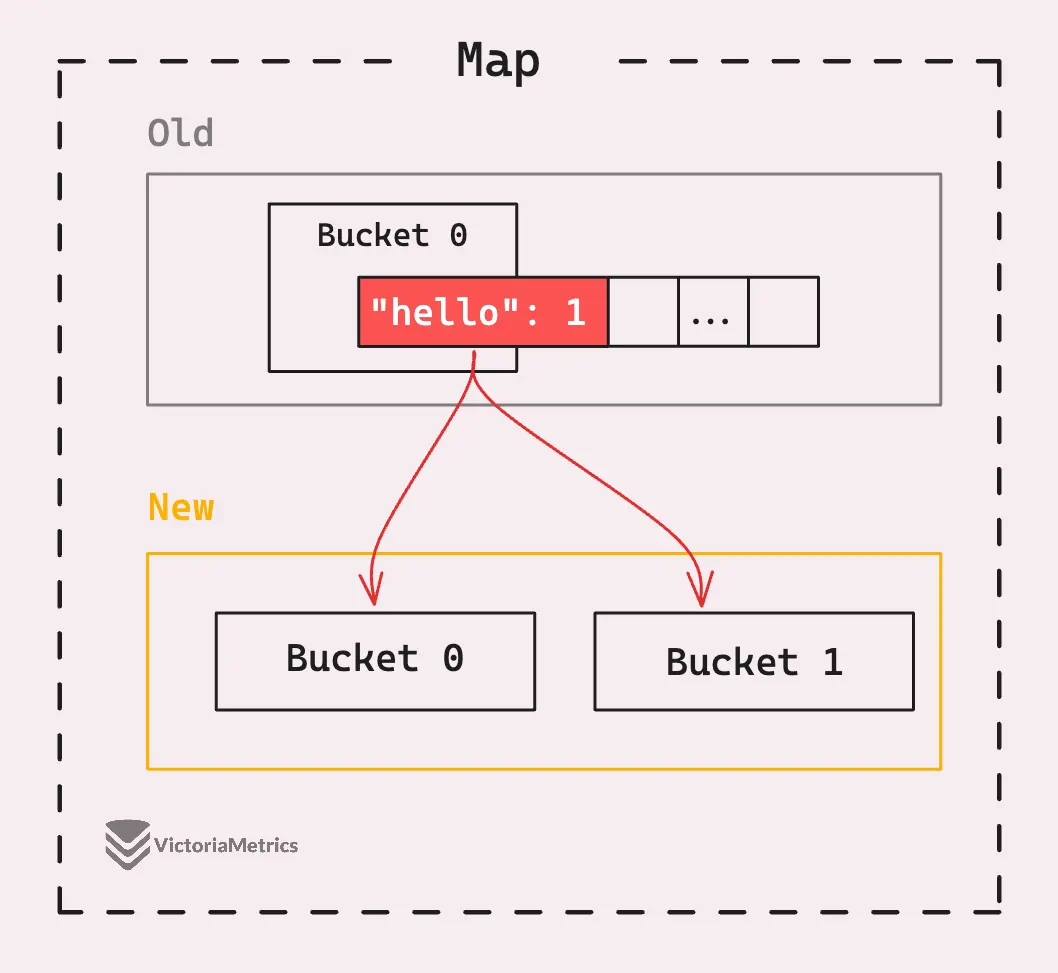

There are only two scenarios where incremental growth kicks in: when you assign a key-value pair to a map or when you delete a key from a map. Either action will trigger the evacuation process and at least one bucket is moved to the new bucket array.

When you assign something like m["Hello"] = 2, if the map is in the middle of growing, the first thing it does is evacuate the old bucket containing the Hello key.

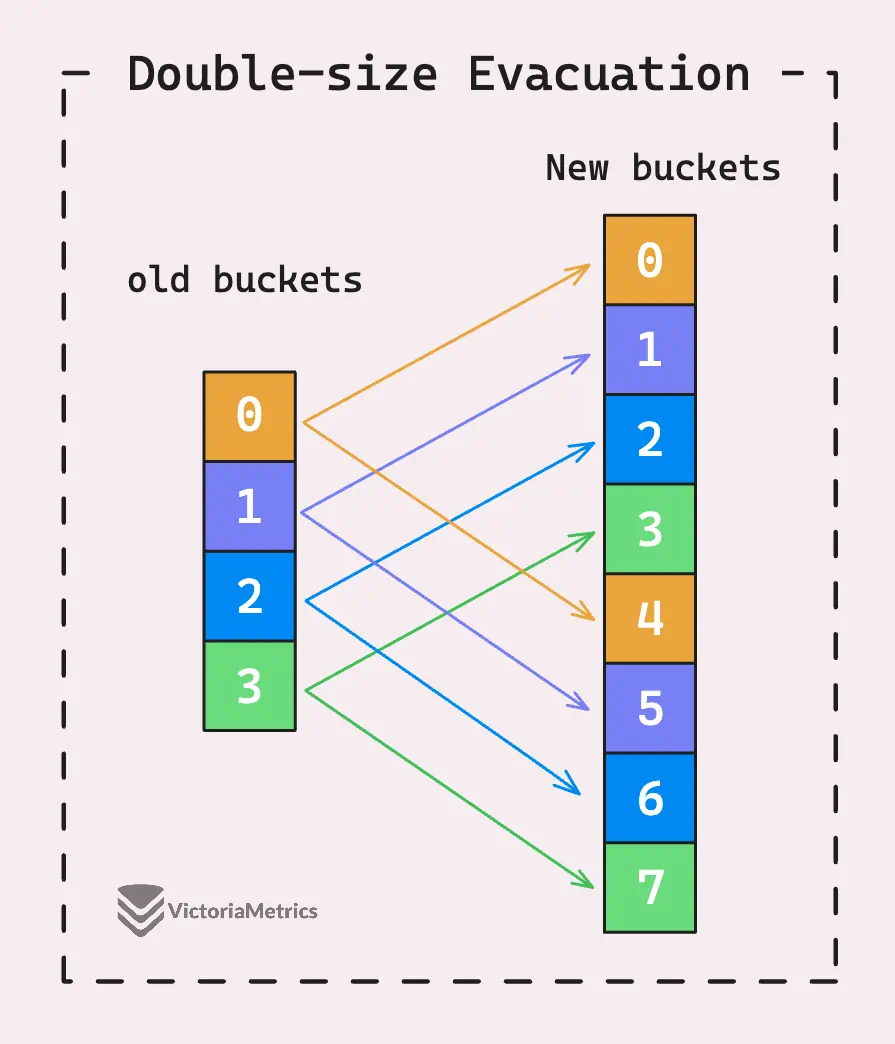

Each element in that old bucket gets moved to one of two new buckets and this same process applies even if the map has more than 2 buckets.

For example, if you’re growing from 4 buckets to 8, the elements in the old bucket 1 will either move to the new bucket 1 or the new bucket 5. How do we know that? It’s just a bit of math involving a bitwise operation.

If a hash % 4 == 1, it means the hash % 8 == 1 or hash % 8 == 5. Because for an old bucket where H % 4 == 1, the last two bits of H are 01. When we consider the last three bits for the new bucket array:

- If the third bit (from the right) is 0, the last three bits are 001, which means

H % 8 == 1. - If the third bit (from the right) is 1, the last three bits are 010, which means

H % 8 == 5.

If the old bucket has overflow buckets, the map also moves the elements from these overflow buckets to the new buckets. After all elements have been moved, the map marks the old bucket as “evacuated” through the tophash field.

That’s all for today discussion, Go map is indeed more complicated than that, with many tiny details that we don’t mention here, for instance, the tophash is not only used for comparison but also for evacuation.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Sync Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- Go Defer: From Basic To Traps

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Inside Go’s Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What Is It?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus