- Blog /

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion

Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion

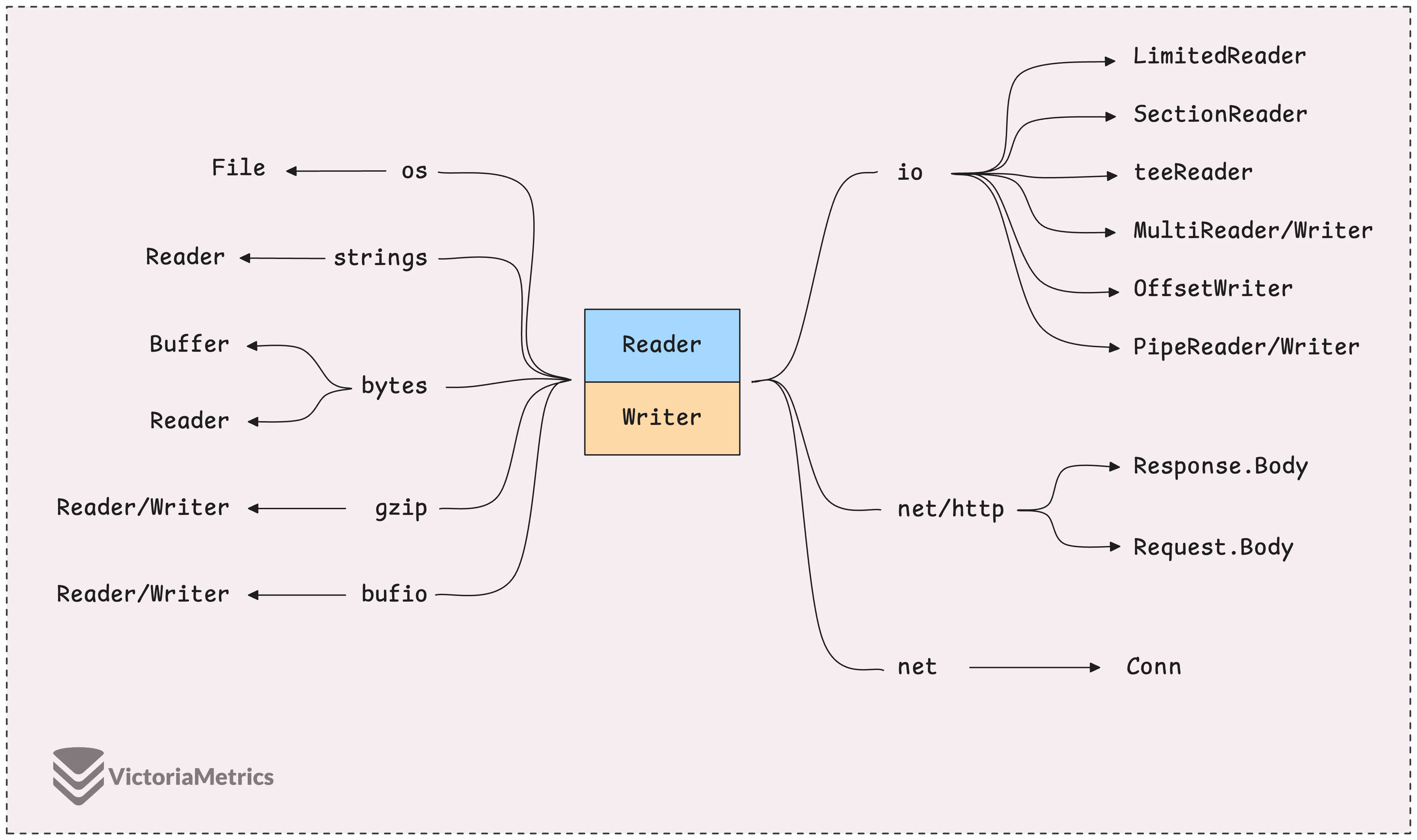

The io.Reader and io.Writer interfaces are probably some of the most common tools you’ll run into when dealing with input and output, but the ecosystem around them is pretty broad.

There are several specific implementations of these interfaces, each one geared toward different tasks, like reading from files, networks, buffers, or even compressed data.

It’s pretty typical to just dive into the ones you need for whatever problem you’re solving at the time and then, over time, you slowly learn about the others.

Today, we’re kicking off the I/O series by taking a look at a lot of these readers and writers, and pointing out some common mistakes — like using io.ReadAll in ways that can backfire.

What is io.Reader?

#

io.Reader is a super simple interface—it’s just got one method:

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

When you call Read, it tries to fill up the slice p with data from a source.

This data source could be anything — a file, a network connection, or even just a plain string. But io.Reader doesn’t care about where the data is coming from. All it knows is that there’s some data, and its job is to copy that data into the slice you gave it.

Read doesn’t promise to fill the whole slice. It returns the amount of data it actually read as n. And when there’s no more data left to read, it’ll return an io.EOF error, which basically means you’ve hit the end of the data stream.

“Can it return both

n(bytes read) and anerr(error) together?”

Yes, and this is where things can get a bit tricky. Sometimes Read will return both a non-zero number of bytes (so n > 0) and an error at the same time.

The key advice here is that you should always process the bytes you’ve read first (if n > 0), even if there’s an error.

The error might not be io.EOF yet — it could be some other issue that happened after reading part of the data. So, you might still get valid data, and you don’t want to miss out on that by jumping straight to handling the error.

“Why doesn’t the Reader return the data but fill the provided byte slice?”

By passing a pre-allocated slice to the Read method, Go gives you more control.

You get to decide how big the slice is, where the data ends up. If the Reader returned a new slice each time, it would create a lot of unnecessary memory allocations, which would slow things down and waste resources.

os.File is a Reader

#

When you want to read from a file, you use os.Open(..), which opens the file and gives you back an *os.File that implements the io.Reader interface.

f, err := os.Open("test.txt")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer f.Close() // no error handling

Once you have the *os.File, you can treat it like any other reader. You read its contents into a buffer and keep reading until you hit io.EOF.

// Make a buffer to store the data

for {

// Read from file into buffer

n, err := f.Read(buf)

// If bytes were read (n > 0), process them

if n > 0 {

fmt.Println("Received", n, "bytes:", string(buf[:n]))

}

// Check for errors, but handle EOF properly

if err != nil {

if err == io.EOF {

break // End of file, stop reading

}

panic(err) // Handle other potential errors

}

}

You can try reducing the buffer size (1024 bytes to 16, 32 bytes, etc.) to see how it affects the output.

io.ReadAll Pitfalls & io.Copy

#

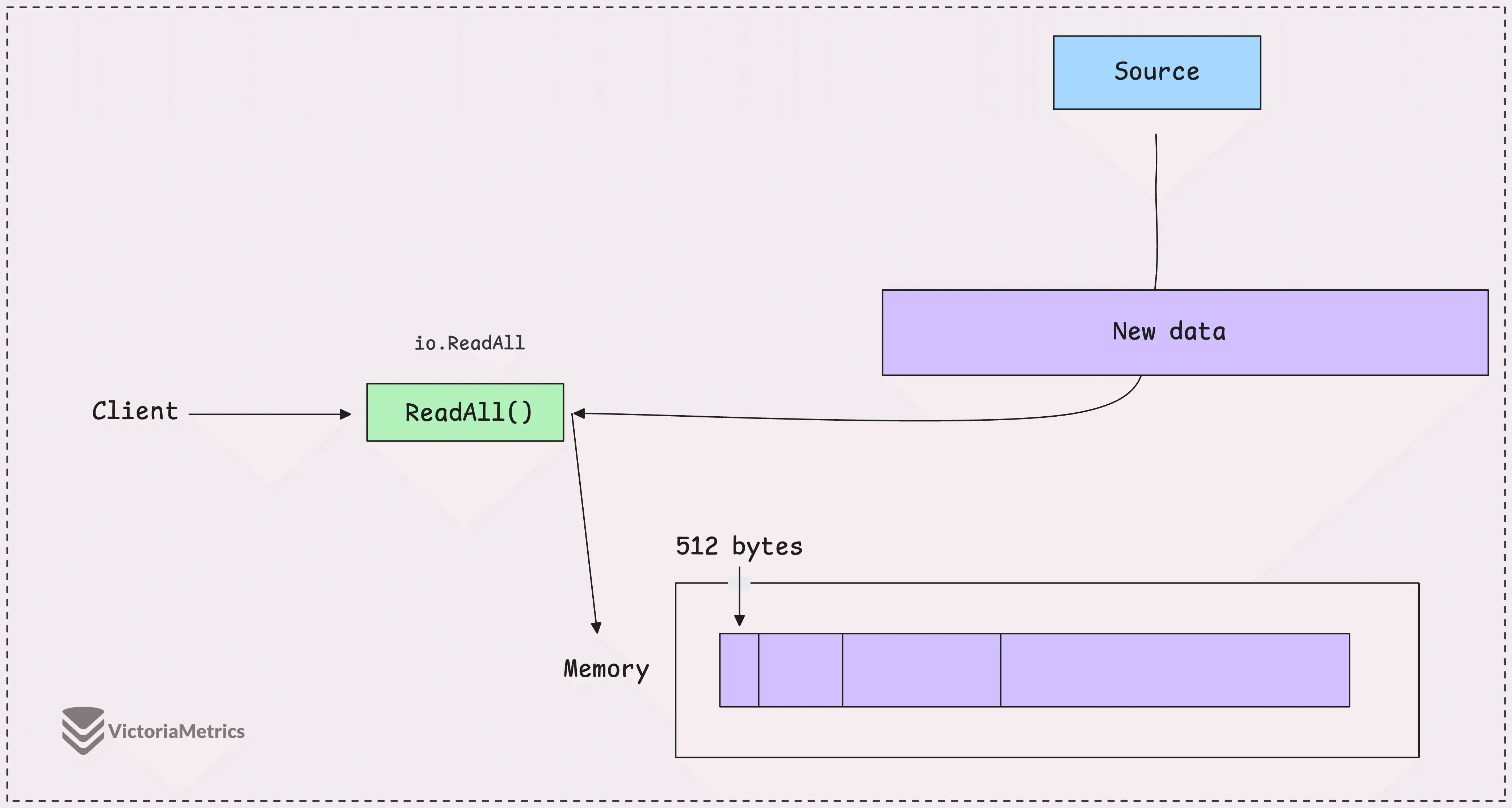

What we just did with reading the file is pretty similar to how a popular utility, io.ReadAll (used to be ioutil.ReadAll), works.

You’ve probably used it in cases where you need to grab all the data at once, like reading the entire body of an HTTP response, loading a full file, or just pulling in everything from a stream.

func main() {

f, err := os.Open("test.txt")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer f.Close() // no error handling

body, err := io.ReadAll(f)

...

}

io.ReadAll is really convenient — it hides all the details of reading the data and automatically handles the growing of the byte slice for you.

It starts with an initial buffer of 512 bytes, and if the data is bigger, the buffer grows using append(). If you’re curious about how append() works or how the buffer size increases, you can look into Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home, but most of the time, you won’t need to worry about it.

Despite its convenience, one major issue is that it doesn’t impose any limit on how much data it reads.

If you call io.ReadAll on a very large data stream, like a massive file or an HTTP response that’s much bigger than expected, the function will keep reading and allocating memory until either it finishes or the system runs out of memory.

Take a scenario where you want to count how many times the letter ‘a’ appears in a file. If you use io.ReadAll to read the entire file first and then count the letter ‘a’, that’s a bit overkill.

In situations like this, io.ReadAll isn’t the best option. Streaming or processing the data incrementally as you read it would be way more efficient.

“So, what should I do? Read it manually?”

Exactly.

You can process each chunk of data as it’s read, count the letter ‘a’, and then move on, without storing the whole file in memory. This solution works well when you’re reading from a file or a network stream, and it allows you to do other things, too.

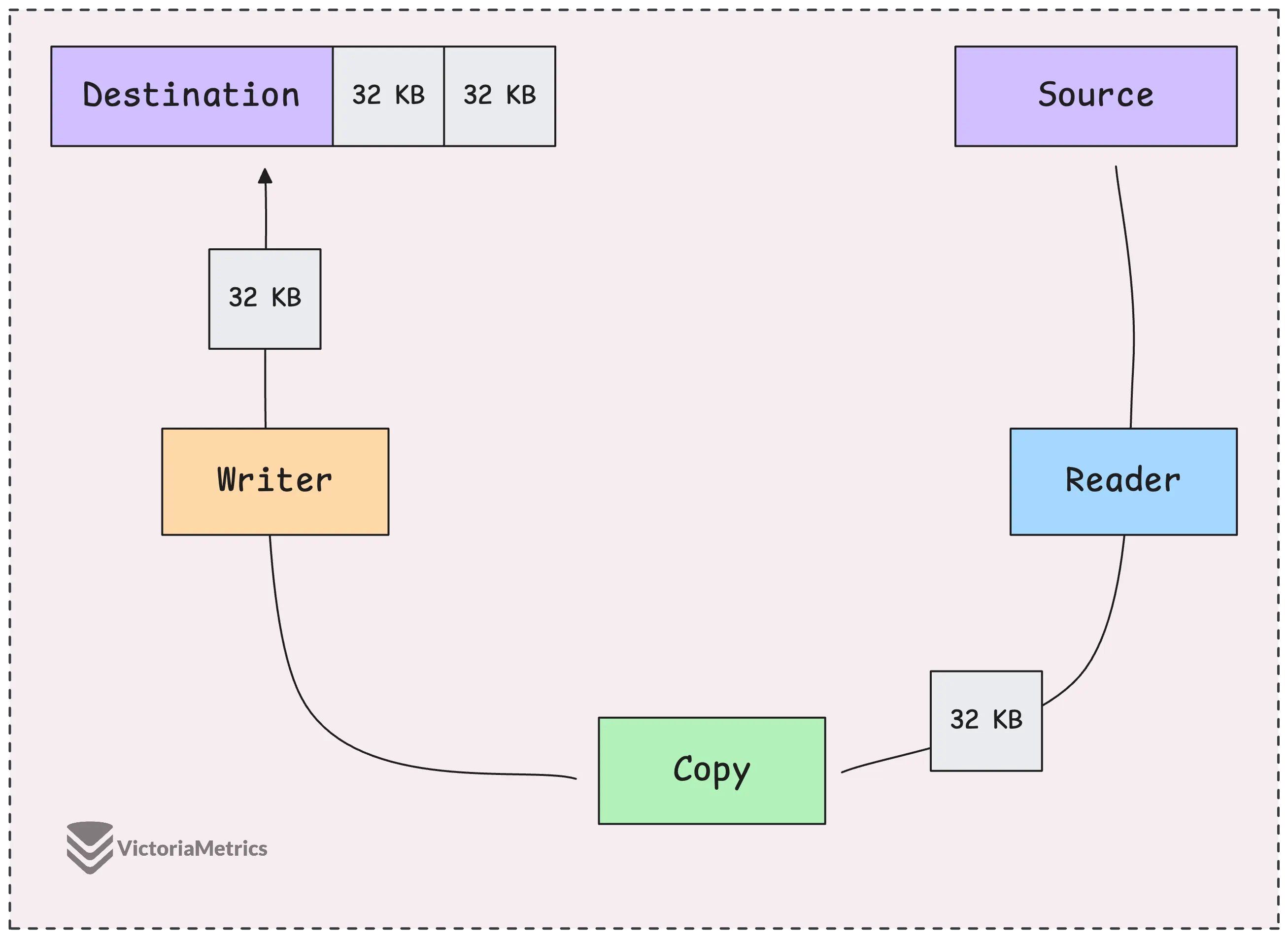

When you’re in these kinds of scenarios: passing data between systems, forwarding an HTTP request body, reading a file and sending it over a network, or downloading something and saving it, you’ve got a great tool: io.Copy - a real lifesaver.

func Copy(dst Writer, src Reader) (written int64, err error) { ... }

The beauty of io.Copy is that it uses a fixed 32KB buffer to handle the transfer.

Instead of loading the whole file into memory, it reads the data in 32KB chunks and writes each chunk directly to the destination, no growing the buffer. This way, your memory usage stays small, no matter how large the data is.

Other Implementations of io.Reader

#

There are a bunch of different io.Reader implementations, but let’s focus on a few common ones. For example, strings.NewReader lets you treat a string as if it’s a stream of data, just like a file or a network response:

r := strings.NewReader("Hello, World!")

This is perfect when you need to simulate reading from a stream - like for testing or creating mock inputs - but your source is something static, like a string. It’s especially useful when you want to integrate it into APIs or functions that expect an io.Reader.

Another important one is http.Response.Body, which is an io.ReadCloser.

It holds the body of an HTTP response, and the key point is, it’s not just an io.Reader, but also a Closer. That means you need to explicitly close it when you’re done reading, so that any resources tied to the response body are released.

resp, err := http.Get("https://example.com")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

r := resp.Body

// Usually, you'd use io.ReadAll to read the full body

// body, err := io.ReadAll(r)

Go’s http.Client uses persistent connections (“keep-alive”), meaning it tries to reuse the same TCP connection for multiple requests to the same server. But if you don’t fully read and close the response body, that connection can’t be reused. So it’s important to make sure the body is fully read and closed when you’re done with it.

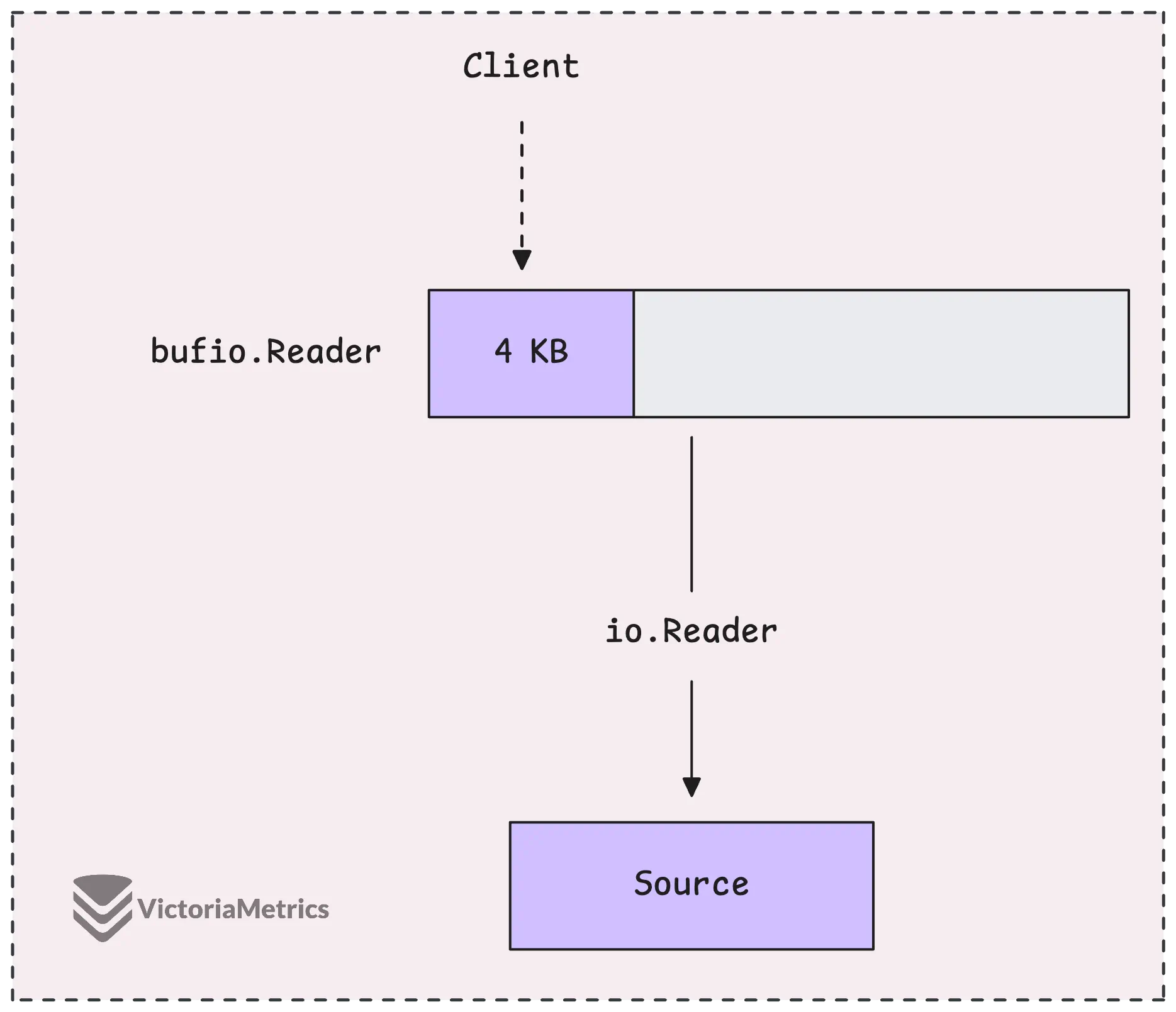

Another useful reader, which shows up a lot in the VictoriaMetrics codebase, is bufio.Reader. It’s designed to wrap around an existing io.Reader and make things more efficient by buffering the input.

r := bufio.NewReader(f)

When you use a bufio.Reader, it doesn’t hit the underlying data source every time you call reader.Read.

Instead, it reads a big chunk of data upfront and stores it in a buffer (by default, that buffer is 4KB). Then, every time you ask for data, it serves it from the buffer. This cuts down how often the reader has to actually interact with the original data source.

Once the buffer runs out of data, it gets another chunk from the source. Now, if you ask for more data than the buffer can hold, bufio.Reader might just skip the buffer altogether and read directly from the source.

Of course, you can also adjust the buffer size if you want, it’s not locked at 4KB:

r := bufio.NewReaderSize(f, 32 * 1024)

The whole point of bufio.Reader is to reduce how often you’re hitting the data source by caching the data in memory.

After going through all the readers above, I believe you probably have a pretty solid grasp on how io.Reader works. So let’s quickly run through some other useful readers:

compress/gzip.Reader: Reads and decompresses gzip data, and also verifies the data’s integrity with checksums and size checks.encoding/base64.NewDecoder: The base64 decoder is also a reader. It takes encoded input and decodes it chunk by chunk, turning every 4 bytes of base64 into 3 bytes of raw data, which it puts into the provided byte slice.io.SectionReader: Think of this as a reader that focuses on a specific slice of data within a larger dataset. You set the section, and it only reads from that portion.io.LimitedReader: This limits the total amount of data that can be read from an underlying reader. It’s not just for a single read; it limits how much can be read over multiple reads.io.MultiReader: Combines multipleio.Readerinstances into one, reading from them sequentially as if they were all concatenated.io.TeeReader: Similar toio.Copy(), but instead of copying all the data at once, it lets you decide when and how much to read while copying the data somewhere else in real time.io.PipeReader: This creates a pipe mechanism where aPipeReaderreads data written by aPipeWriter. It blocks the read until there’s data to read, which makes it a simple way to synchronize between a reader and a writer.

Most of these readers wrap around another io.Reader — whether that’s a base io.Reader or something like bufio.Reader (which itself wraps around an io.Reader). Same goes for utilities like io.ReadAll(r Reader), if you recall.

Now, if you wanted to create your own reader, you’d basically follow the same pattern. For instance, here’s a concurrency-limiting reader used in VictoriaMetrics:

type Reader struct {

r io.Reader

increasedConcurrency bool

}

// Read implements io.Reader.

//

// It increases concurrency after the first call or after the next call after DecConcurrency() call.

func (r *Reader) Read(p []byte) (int, error) {

n, err := r.r.Read(p)

if !r.increasedConcurrency {

if !incConcurrency() {

err = &httpserver.ErrorWithStatusCode{

Err: fmt.Errorf("cannot process insert request for %.3f seconds because %d concurrent insert requests are executed. "+

"Possible solutions: to reduce workload; to increase compute resources at the server; "+

"to increase -insert.maxQueueDuration; to increase -maxConcurrentInserts",

maxQueueDuration.Seconds(), *maxConcurrentInserts),

StatusCode: http.StatusServiceUnavailable,

}

return 0, err

}

r.increasedConcurrency = true

}

return n, err

}

This custom reader wraps around any io.Reader, and its main job is to limit how many concurrent read operations are allowed at once. If the limit is reached, it queues further reads until resources are available or a timeout hits.

What is io.Writer?

#

The method signature of io.Writer’s Write method looks a lot like the io.Reader’s Read method:

type Writer interface {

Write(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}

The Write method tries to write the contents of the byte slice p to some predefined destination, like a file or network connection.

The return value n tells you how many bytes were actually written. Ideally, n should be the same as len(p) — meaning the whole slice was written — but that’s not always guaranteed. If n is less than len(p), it means only part of the data was written, and err will tell you what went wrong.

Now that we’ve gone over io.Reader, the writer counterpart is pretty straightforward to understand.

For example, os.File is also a writer:

func main() {

f, err := os.Open("test.txt")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer f.Close() // no error handling

_, err = f.Write([]byte("Hello, World!"))

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

// panic: write test.txt: bad file descriptor

In this case, the error bad file descriptor happens because os.Open opens the file in read-only mode, so you can’t write to it. To fix it, you need to open the file in a mode that allows writing.

You can use os.OpenFile, which gives you more control over how the file is opened:

f, err := os.OpenFile("test.txt", os.O_RDWR|os.O_CREATE, 0o644)

This will work just fine now. Go will write to the beginning of the file and overwrite the existing content, if you want to append instead, you can add os.O_APPEND to the options.

Another useful writer is definitely bufio.Writer, which works just like bufio.Reader but for writing, which can improve performance by reducing the number of writes.

It wraps an io.Writer and buffers the data:

type Writer struct {

err error

buf []byte

n int

wr io.Writer

}

bufio.Writer doesn’t immediately write the data to the underlying writer. Instead, it copies the data into an internal buffer. If there’s enough room (the default buffer size is 4KB), it holds the data in the buffer until it fills up, then writes everything at once.

func main() {

f, err := os.OpenFile("test.txt", os.O_RDWR|os.O_CREATE, 0o644)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer f.Close() // no error handling

w := bufio.NewWriter(f)

_, err = w.Write([]byte("Hello, World!"))

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

One thing to watch out for is that bufio.Writer won’t write anything to the file until the buffer is full or you manually flush it. If you run the code above and don’t call Flush(), the data might not get written, even when the program ends. This can lead to data loss.

So, always make sure to call Flush() after writing to force any buffered data to be written out.

func main() {

...

if err = w.Flush(); err != nil {

panic(err)

}

}

You might also be familiar with a handy utility for formatted output: fmt.Fprintf and fmt.Fprintln.

fmt.Fprintln(os.Stdout, "Hello VictoriaMetrics")

This writes formatted data to any io.Writer. In this case, os.Stdout is the terminal or console, and it’s great when you need to write formatted strings directly to a file or any other writer.

And that’s it for the first part of the I/O series! Nothing too complicated, but also not too basic either.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus