- Blog /

- How HTTP/2 Works and How to Enable It in Go

How HTTP/2 Works and How to Enable It in Go

This article is part of the ongoing gRPC communication protocol series:

- From net/rpc to gRPC in Go Applications

- How HTTP/2 Works and How to Enable It in Go (We’re here)

- Practical Protobuf - From Basic to Best Practices

- How Protobuf Works—The Art of Data Encoding

- gRPC in Go: Streaming RPCs, Interceptors, and Metadata

Once you’re comfortable with net/rpc from previous article (From net/rpc to gRPC in Go Applications), it’s probably a good idea to start exploring HTTP/2, which is the foundation of the gRPC protocol.

This piece leans a bit more on the theory side, so heads-up, it’s text-heavy. We’ll focus on understanding HTTP/2 and then briefly touch on enabling it in Go. So, grab a coffee, settle in, and let’s break it down.

Why HTTP/2?

#

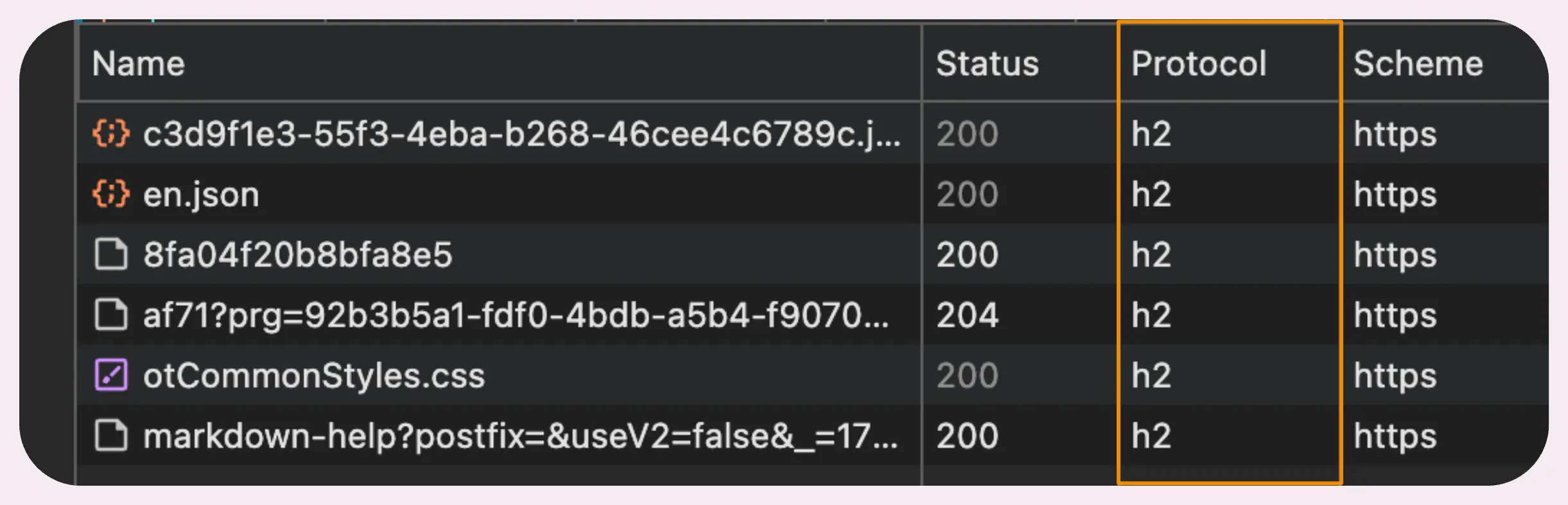

HTTP/2 is a major upgrade over HTTP/1.1, and these days, it’s pretty much the default everywhere. If you’ve ever opened up Chrome DevTools to check out network requests, chances are you’ve already seen HTTP/2 connections in action.

But why is HTTP/2 such a big deal? What’s the story with HTTP/1.1?

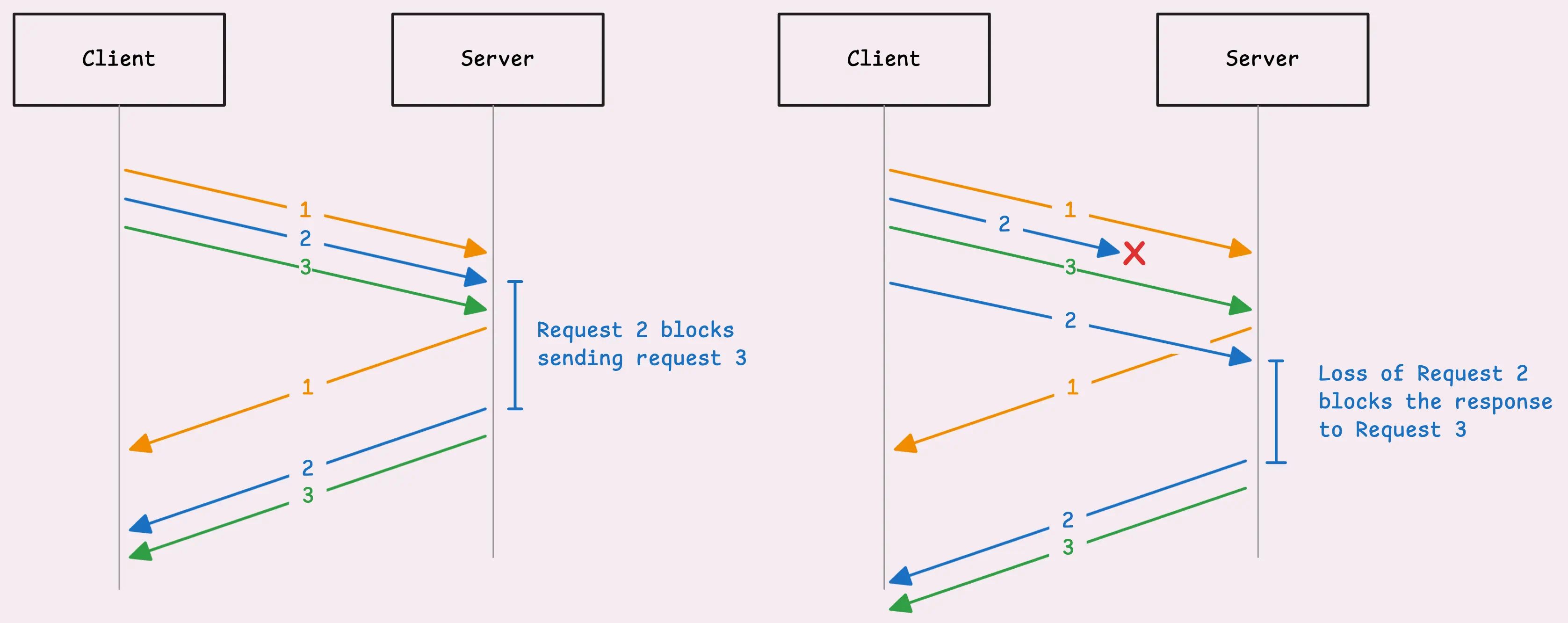

Now, HTTP/1.1 did bring in pipelining, which, on paper, looked like a solid improvement. The idea was simple: multiple requests could share a single connection and fire off without waiting for the previous one to finish.

The problem was that requests had to go out in order, and responses had to come back in the same order. If one response got delayed—maybe the server needed extra time to process it—everything else in the queue had to wait.

This also happens if there’s a network “hiccup” that delays just one request. The whole response pipeline stalls until that delayed request gets through.

To work around this limitation, HTTP/1.1 clients (like your browser) started opening multiple TCP connections to the same server, allowing requests to flow more freely and concurrently.

And while it worked, it wasn’t exactly efficient:

- More connections meant more resources used on both the client and server sides.

- TCP has to go through a handshake process for each connection, which adds extra latency.

“So, does HTTP/2 fix this problem?”

It does… well, mostly.

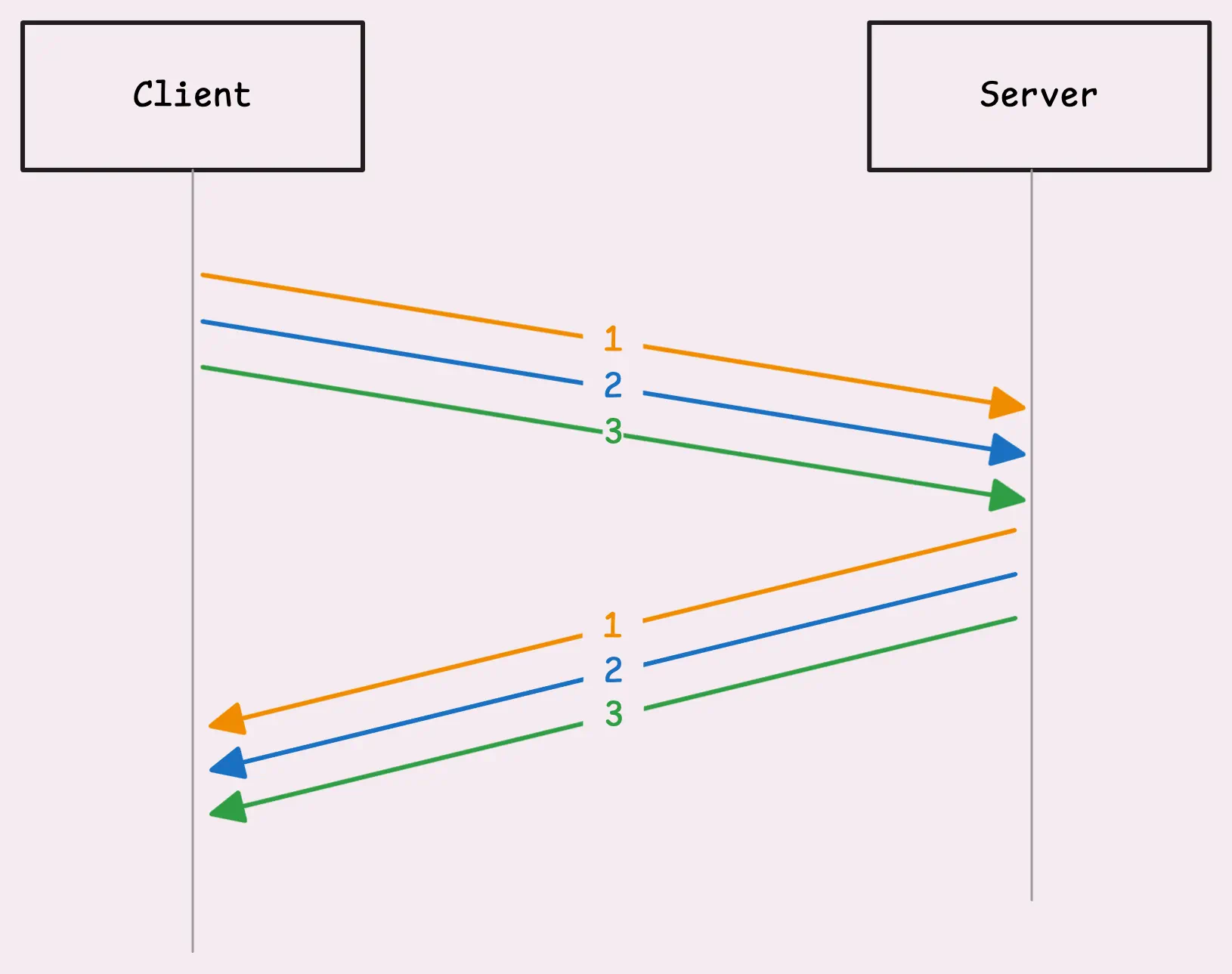

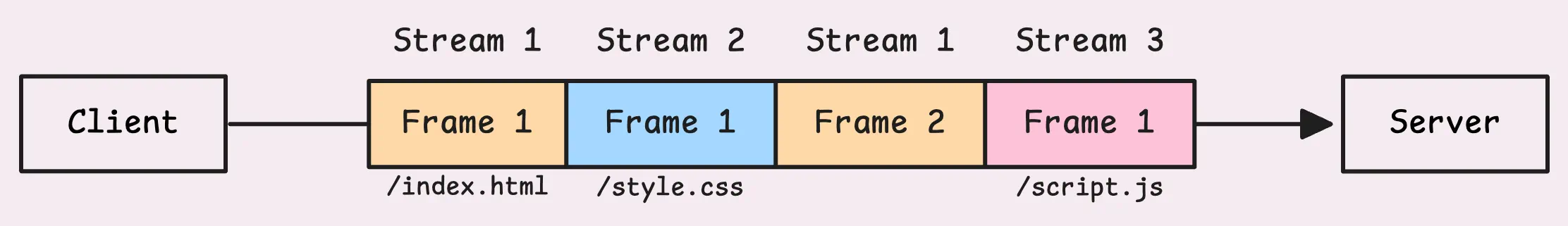

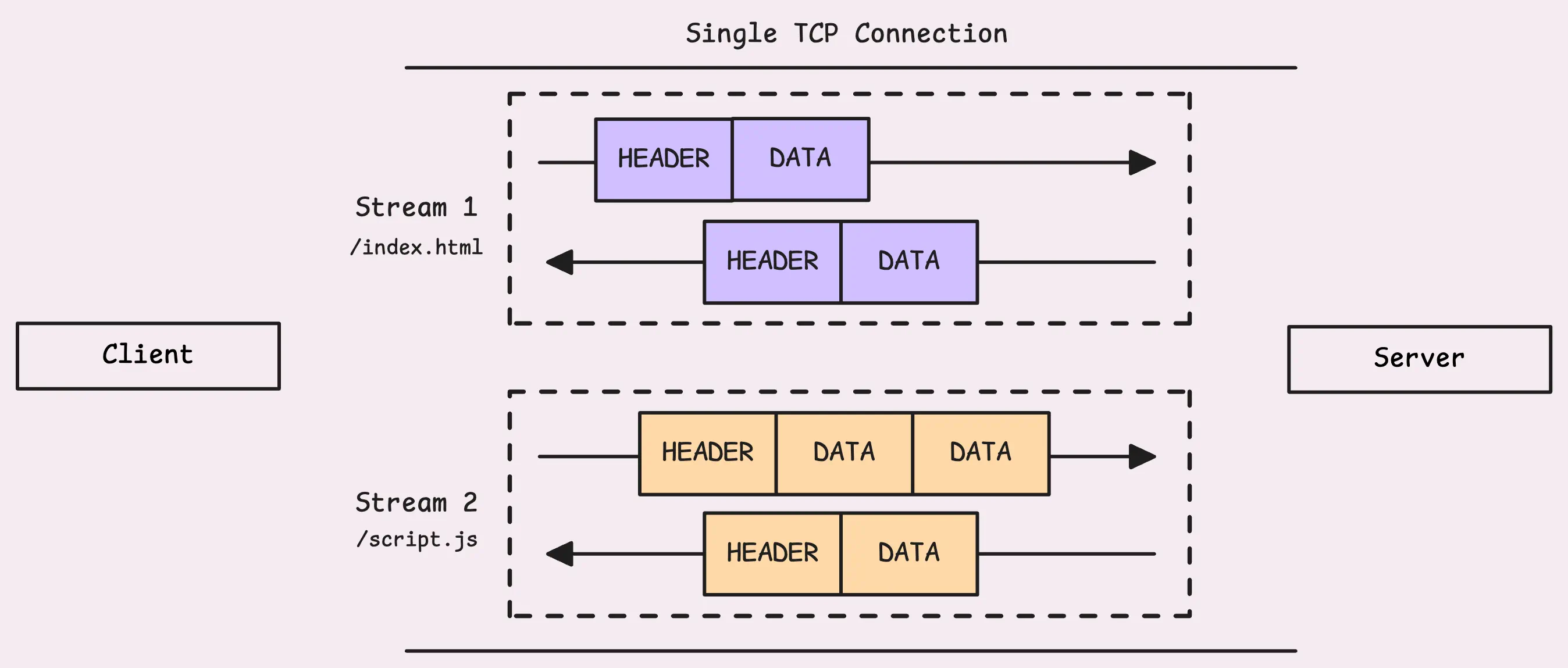

HTTP/2 takes that single connection and splits it into multiple independent streams. Each stream has its own unique ID, called a stream ID, and these streams can work in parallel. This setup fixes the Head-of-Line (HoL) blocking issue at the application layer (where HTTP sits). If one stream gets delayed, it doesn’t stop the others from moving forward.

But HTTP/2 still runs on TCP, so it doesn’t completely escape HoL blocking.

At the transport layer, TCP insists on delivering packets in order for application layer. If one packet goes missing or gets delayed, TCP makes everything else wait until it can sort out that missing piece. Once the delayed packet shows up, TCP happily delivers those queued packets in the correct order to HTTP/2 layer (or application layer).

So, even if all the other streams’ data is sitting in the buffer ready to go, the server still has to wait for the delayed stream’s data to arrive before it can process the rest.

If you want to fully get around TCP’s limitations, you’d be looking at something like QUIC which is built on top of UDP (User Datagram Protocol), and it powers HTTP/3.

Of course, HTTP/2 doesn’t just fix the pain points of HTTP/1.1, it also opens the door to new possibilities. Let’s take a closer look at how it all comes together.

How Does HTTP/2 Work?

#

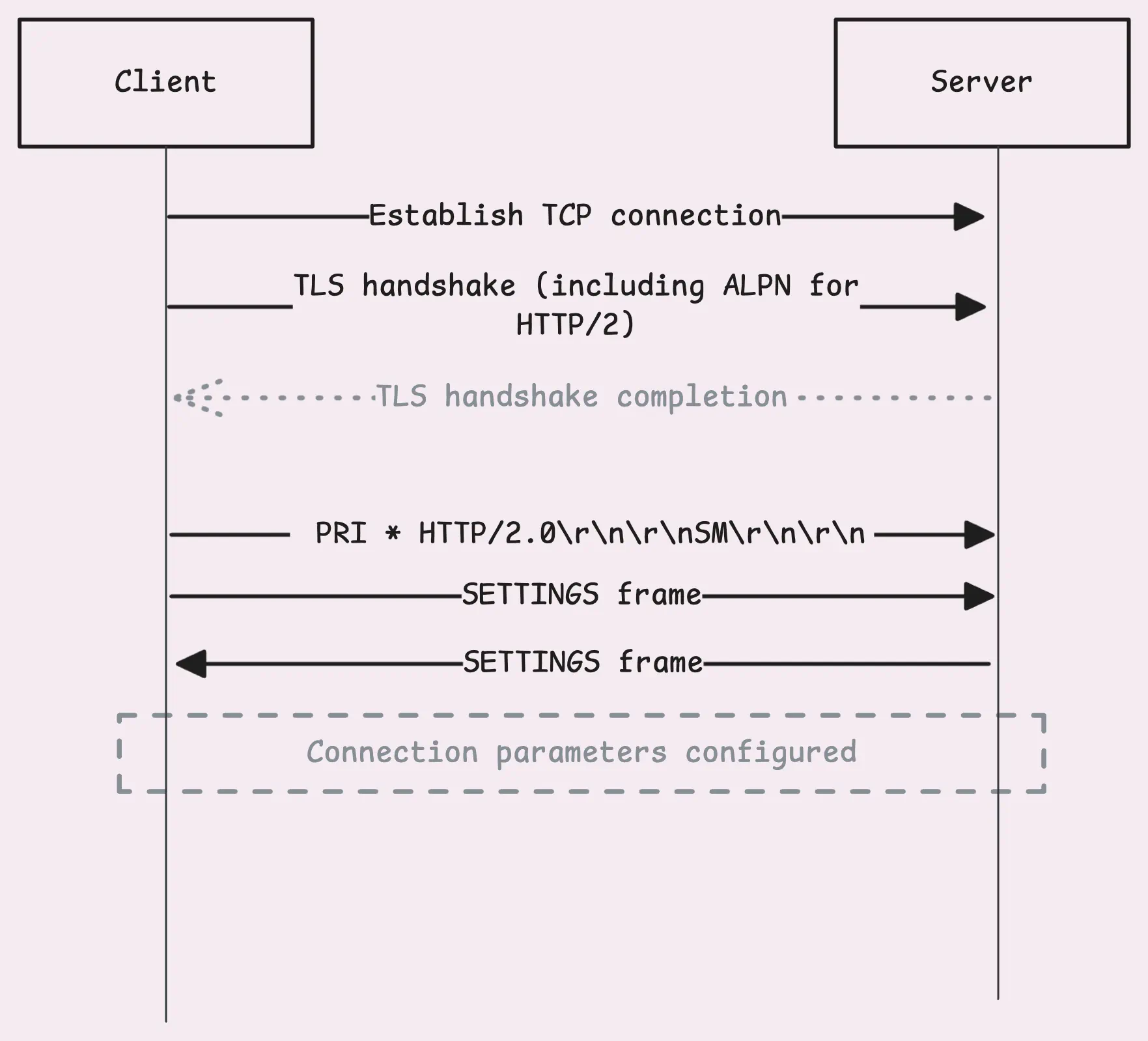

When a client is setting up a TLS connection, the process kicks off with a ClientHello message. This message includes an ALPN (Application Layer Protocol Negotiation) extension, which is basically a list of protocols the client supports. Usually, it includes both “h2” for HTTP/2, “http/1.1” as a fallback option, and others.

The server’s TLS stack then checks this list against the protocols it supports. If both sides agree on “h2,” the server confirms the choice in its ServerHello response.

From there, the TLS handshake continues as usual, setting up encryption keys, verifying certificates, and so on.

Connection Preface

#

Once the handshake wraps up, the client sends something called a connection preface. It kicks off with a very specific 24-byte sequence: PRI * HTTP/2.0\r\n\r\nSM\r\n\r\n. This sequence confirms that HTTP/2 is the protocol being used. At this stage, there’s no compression or framing yet.

Right after sending the connection preface, the client follows up with a SETTINGS frame. This isn’t tied to any stream; it’s a connection-level control frame, a message to the server that says: “Here are my preferences.” This includes settings like flow control options, the maximum frame size, etc.

The server recognizes what the client is aiming for and responds with its own connection preface, which includes a SETTINGS frame of its own.

Once that exchange is complete, the connection setup is good to go.

HEADERS Frame & HPACK Compression

#

The client is now ready to send a request, it creates a new stream with a unique ID called stream ID. The stream ID for client-initiated streams is always an odd number — 1, 3, 5,…

You might wonder why the stream IDs are odd instead of being numbered like 1, 2, 3… There’s actually a neat little rule here:

- Odd-numbered streams are for requests initiated by the client.

- Even-numbered streams are for the server, often for server-initiated features like server push.

- Stream ID 0 is special, it’s used only for connection-level (not stream-level) control frames that apply to the whole connection.

Once the stream is ready, the client sends a HEADERS frame.

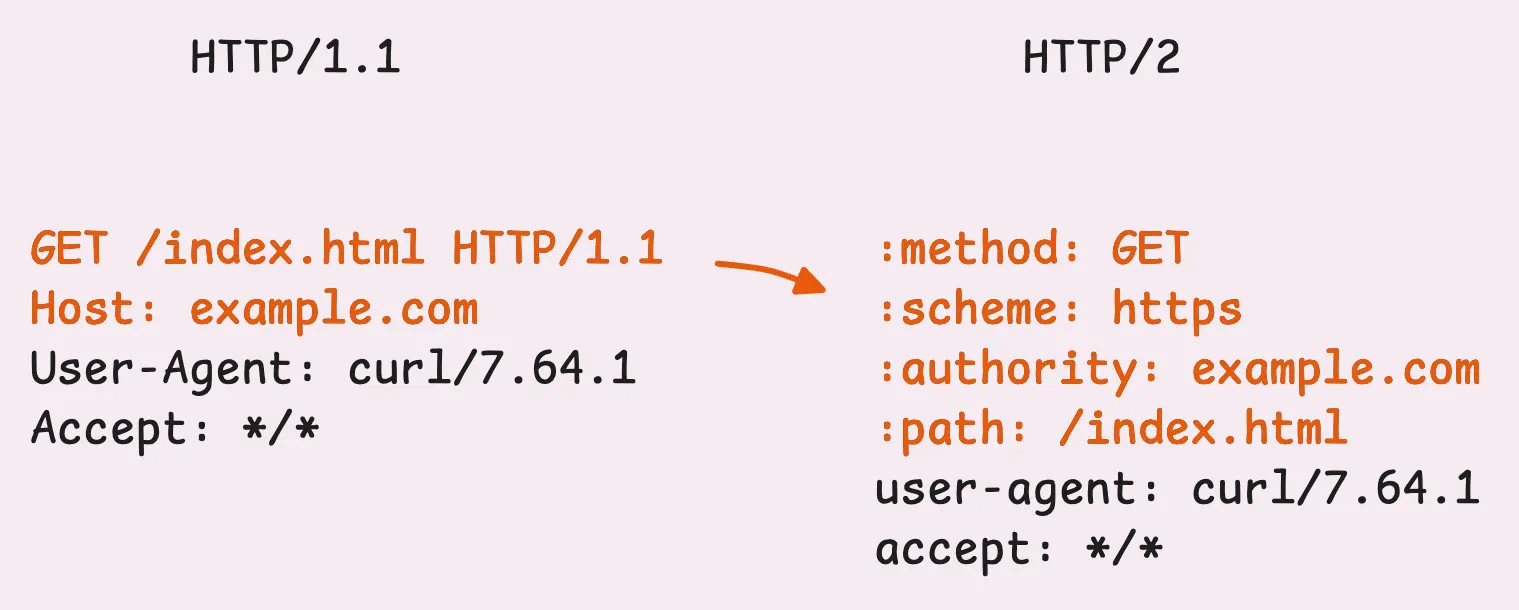

This frame contains all the header info you’d expect—the equivalent of the HTTP/1.1 request line and headers (think GET / HTTP/1.1 and everything that follows). But the headers are structured and transmitted a bit differently.

- Structure: HTTP/2 introduces pseudo-headers, which help define things like the method, path, and status. These’re then followed by the familiar headers like

User-Agent,Content-Type,… - Transmission: Headers are compressed using the HPACK algorithm and sent in binary format.

“Pseudo-header? HPACK compression? What’s going on here? “

Let’s unpack this, starting with pseudo-headers.

If you’ve poked around in Chrome’s DevTools or any other inspector, this might already look familiar.

With HTTP/2, pseudo-headers are a way to keep special headers separate from the regular ones. These special headers, like :method, :path, :scheme, and :status always come first. After those, the regular headers like Accept, Host, and Content-Type follow in the usual format.

In HTTP/1.1, this kind of info was scattered across the request line and headers. It wasn’t the cleanest setup and relied on conventions or context to fill in the blanks. For example:

- The scheme (HTTP or HTTPS) was implied by the connection type. If it was TLS on port 443, you just knew it was HTTPS.

- The

Hostheader, added in HTTP/1.1 for virtual hosting, was just another regular header, not a formal part of the request structure.

With HTTP/2’s pseudo-headers (those ones starting with a colon, like :method or :path), all that ambiguity is gone.

“What about HPACK compression?”

Unlike HTTP/1.1, where headers are plain text and separated by newlines (\r\n), HTTP/2 uses a binary format to encode headers. This is where HPACK compression comes in, an algorithm built specifically for HTTP/2. It doesn’t just shrink headers to save space, it also avoids sending the same header data repeatedly.

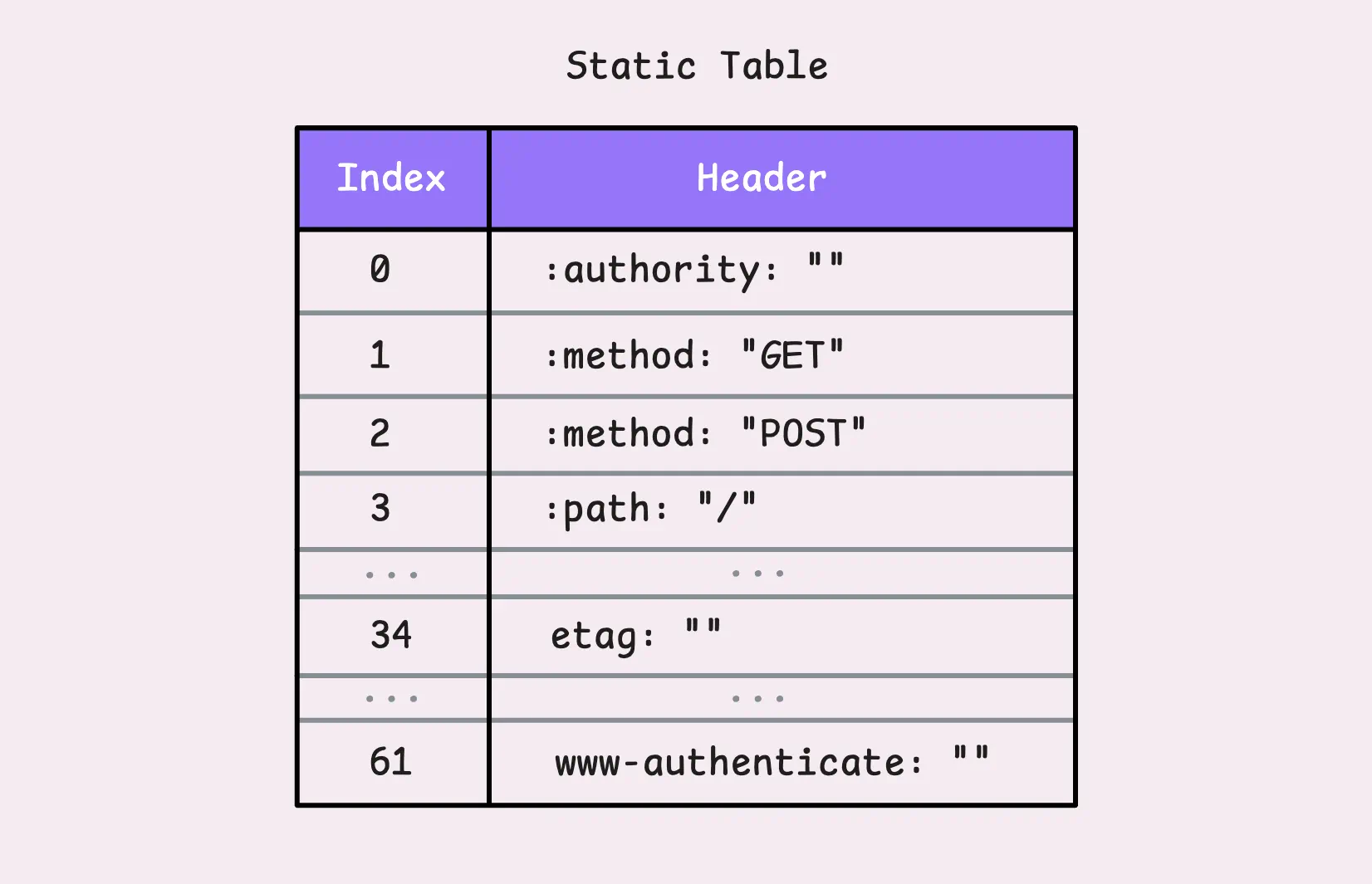

HPACK uses two clever tables to manage headers: a static table and a dynamic table.

The static table is like a shared dictionary that both the client and server already know. It holds 61 of the most common HTTP headers. If you’re curious about the details, you can check out the static_table.go file in the net/http2 package here.

Let’s say you send a GET request with the header :method: GET.

Instead of transmitting the entire header, HPACK might just send the number 2. That single number refers to the key-value pair :method: GET in the static table and everyone in the party knows what it means.

If the key matches but the value doesn’t, like etag: some-random-value, HPACK can still reuse the key (which is 34 in this case) and just send the updated value. This way, the header name isn’t retransmitted in full.

“So what happens to

some-random-value?”

It gets encoded using Huffman coding and sent as 34: huffman("some-random-value") (pseudo-code). But what’s interesting is, the entire header, etag: some-random-value, is added to the dynamic table.

The dynamic table starts empty and grows as new headers (not in the static table) are sent. This makes HPACK stateful, meaning both the client and server maintain their own dynamic tables for the duration of the connection.

Each new header added to the dynamic table gets a unique index, starting at 62 (since 1-61 are reserved for the static table). From then on, that index is used instead of retransmitting the header. This setup has a couple of key traits:

- Connection-level: The dynamic table is shared across all streams in a single connection. Both the server and client maintain their own copies.

- Size limit: By default, the dynamic table’s maximum size is set to 4 KB (4,096 octets), which can be adjusted via the

SETTINGS_HEADER_TABLE_SIZEparameter in theSETTINGSframe. When the table gets full, older headers are evicted to make room for new ones.

DATA Frame

#

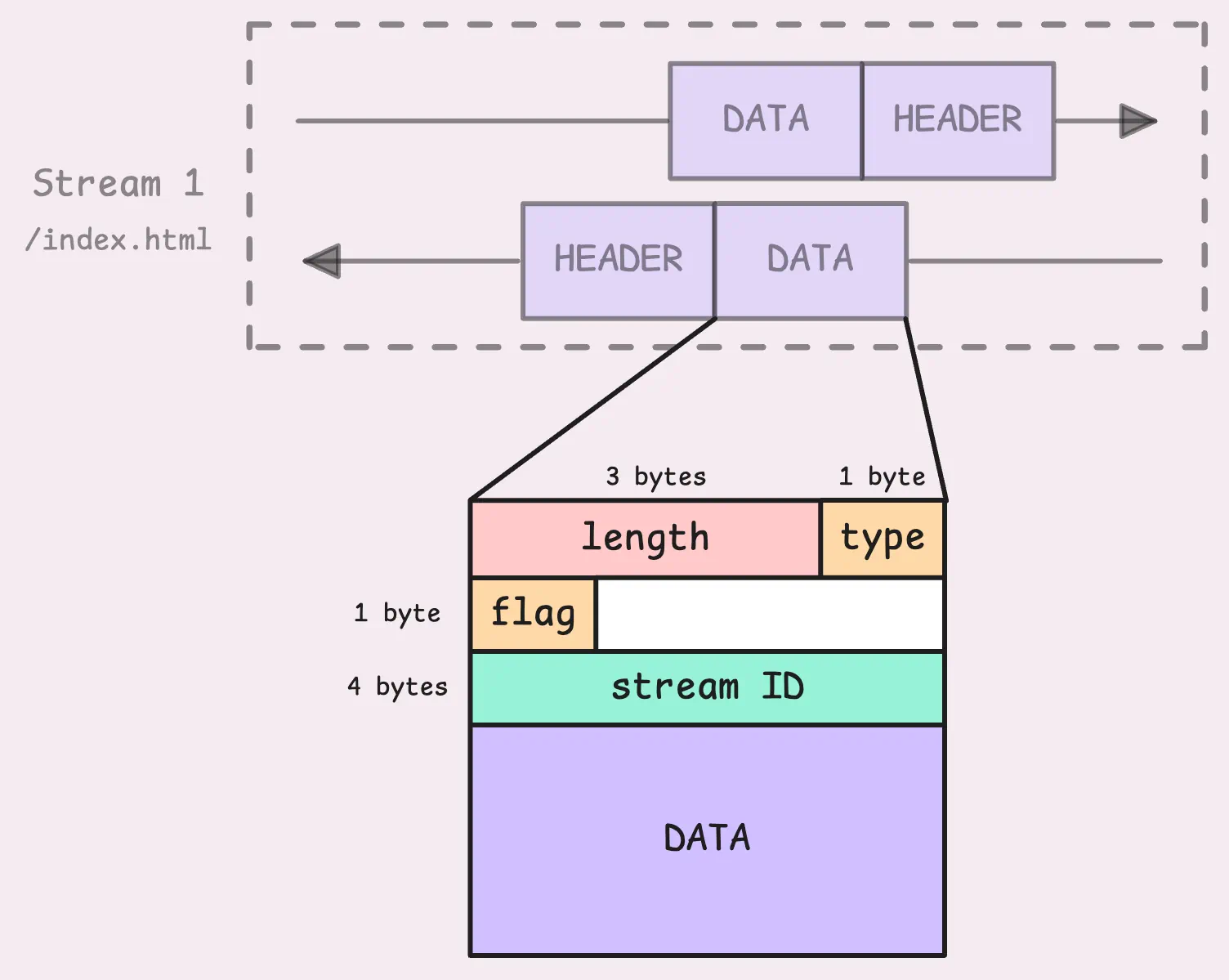

If there’s a request body, it gets sent in DATA frames. And if the body is larger than the maximum frame size (defaulting to 16 KB), it’s broken into multiple DATA frames, all sharing the same stream ID.

“So, where’s the stream ID in the frame?”

Good question. We haven’t talked about frame structure yet.

Frames in HTTP/2 aren’t just containers for data or headers. Every frame includes a 9-byte header. This isn’t the kind of HTTP header we discussed earlier, it’s a frame header.

So here’s the breakdown: we’ve got the length, which tells us the size of the frame payload (excluding the frame header itself). Then there’s the type, which identifies what kind of frame it is (e.g. DATA, HEADERS, PRIORITY, and so on). Next up are the flags, which provide extra details about the frame. For example, the END_STREAM flag (0x1) signals that no more frames will follow on this stream.

And finally, we’ve got the stream ID. This is a 32-bit number that identifies which stream the frame belongs to (the most significant bit is reserved and must always be set to 0).

“But what about the order of frames in a stream? What if they arrive out of order?”

Yes, while the stream ID tells us which stream a frame belongs to, it doesn’t specify the order of frames.

We will find the answer in the TCP layer. Since HTTP/2 runs over TCP, the protocol guarantees sequential delivery of packets. Even if packets take different paths across the network, TCP ensures they show up at the receiver in the exact order they were sent.

This ties back to the HoL blocking issue we discussed earlier.

When the server gets a HEADERS frame, it creates a new stream using the same stream ID as the request.

It starts by sending back its own HEADERS frame, which contains the response status and headers (compressed with HPACK). After that, the response body is sent in DATA frames. Thanks to multiplexing, the server can interleave frames from multiple streams, sending chunks of different responses over the same connection simultaneously.

On the client side, the response frames are sorted using their stream ID. The client decompresses the HEADERS frame and processes the DATA frames in order.

Everything stays aligned, even when multiple streams are active at once.

Flow Control

#

When a frame comes in with the END_STREAM flag set (bit 1 of the flags field in the frame header is flipped to 1), it’s a signal. It tells the receiver, “That’s it, no more frames are coming on this stream.” At this point, the server can send back the requested data and wrap up the stream with its own END_STREAM flag in the response.

But ending the stream doesn’t close the entire connection. The connection stays open for other streams to continue doing their thing.

If the server needs to close the connection itself, it uses a GOAWAY frame. This is a connection-level control frame designed for a graceful shutdown.

When the server sends a GOAWAY frame, it includes the last stream ID it plans to handle. The message is essentially saying, _“I’m wrapping up, any streams with higher IDs won’t be processed, but everything else that’s in progress can finish normally.” _That’s why it’s considered a graceful shutdown.

After sending GOAWAY, the sender usually waits a little while to let the receiver process the message and stop sending new streams. This short pause helps avoid a harsh TCP reset (RST), which would otherwise kill all streams immediately and cause chaos.

There are also a few other handy tools in the HTTP/2 toolkit. Throughout a connection, either side can send WINDOW_UPDATE frames to manage flow control, PING frames to check if the connection is still alive, and PRIORITY frames to fine-tune stream priorities. And if things go wrong, RST_STREAM frames can step in to shut down individual streams without affecting the rest of the connection.

And that wraps up the HTTP/2 story. Next, let’s take a look at how this all works in Go.

HTTP/2 in Go

#

You might not even notice it, but the net/http package in Go already supports HTTP/2 out of the box.

“Wait, so it’s just enabled by default?”

Well, yes and no.

If your service runs over HTTPS, HTTP/2 is likely being used automatically. But if it’s running on plain HTTP, then probably not. Here are some common scenarios where HTTP/2 might not kick in:

- Your service runs on plain HTTP, using a simple

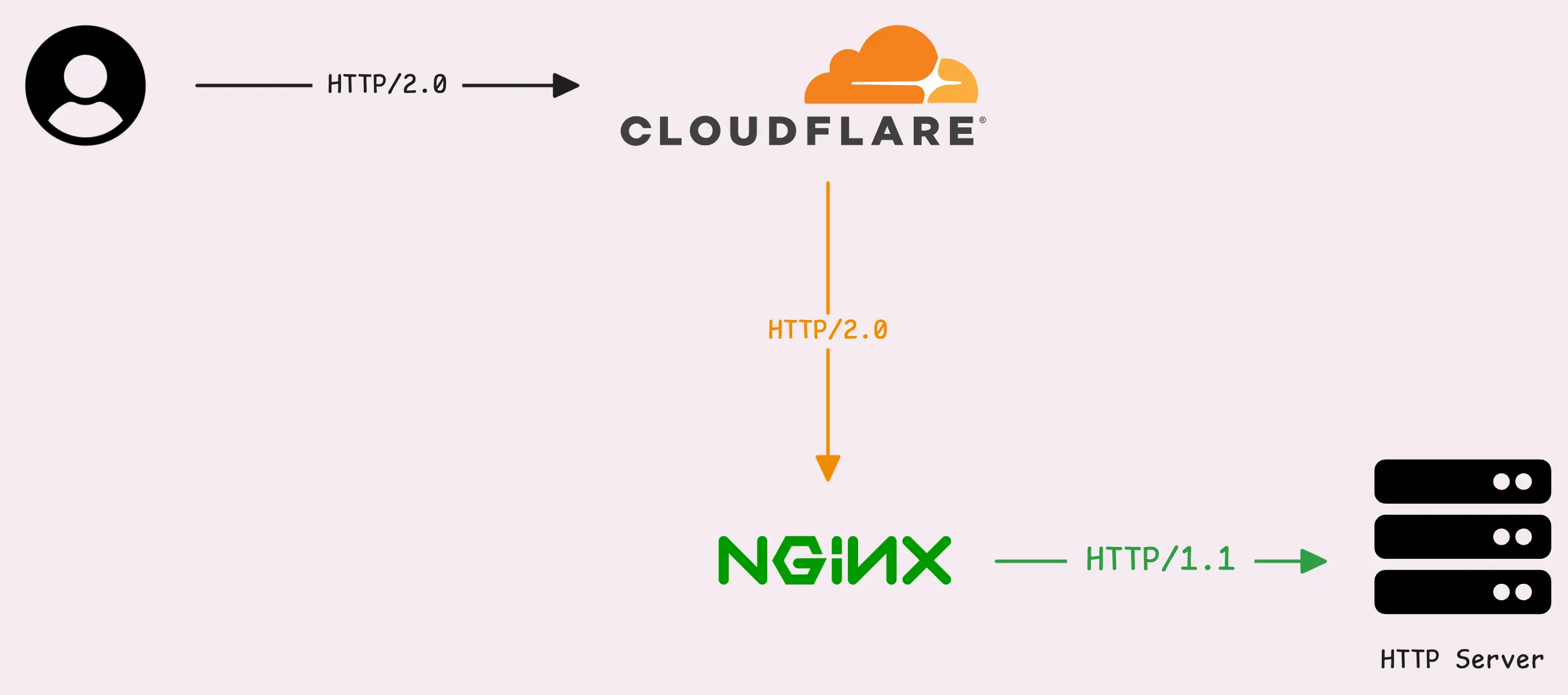

ListenAndServe. - You’re behind a Cloudflare proxy. In this case, requests from users to Cloudflare might use HTTP/2, but the connection from Cloudflare to your service (the origin) typically sticks to HTTP/1.1.

- You’re behind Nginx with HTTP/2 enabled. Nginx acts as the TLS termination point, decrypting the request and re-encrypting the response, while forwarding everything to your service over HTTP/1.1.

If you want your service to use HTTP/2 directly, you’ll need to set it up with SSL/TLS.

Technically, you can run HTTP/2 without TLS, but it’s not standard practice for external traffic. However, it could be used in internal environments like microservices or private networks. That said, it’s worth experimenting with if you’re curious.

Even if you run HTTP/2 without TLS, the client might still default to HTTP/1.1. The solution below doesn’t guarantee that the clients (external services) will use HTTP/2 with your HTTP server.

Let’s try a simple example to see this in action. We’ll start with a basic server running plain HTTP on port 8080:

func getRequestProtocol(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "Request Protocol: %s\n", r.Proto)

}

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/", getRequestProtocol) // Root endpoint

if err := http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil); err != nil {

fmt.Printf("Error starting server: %s\n", err)

}

}

And here’s a basic HTTP client to test it:

func main() {

resp, _ := (&http.Client{}).Get("http://localhost:8080")

defer resp.Body.Close()

body, _ := io.ReadAll(resp.Body)

fmt.Println("Response:", string(body))

}

// Response: Request Protocol: HTTP/1.1

We’ll skip error handling here to keep the focus on the core idea.

From the output, you can see that both the request and response are using HTTP/1.1, just as expected. Without HTTPS or specific configuration, HTTP/2 doesn’t come into play here.

By default, the Go HTTP client uses a DefaultTransport, which is already set up to handle both HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2. There’s even a handy field called ForceAttemptHTTP2, which is turned on by default:

var DefaultTransport RoundTripper = &Transport{

...

ForceAttemptHTTP2: true, // <---

MaxIdleConns: 100,

IdleConnTimeout: 90 * time.Second,

TLSHandshakeTimeout: 10 * time.Second,

ExpectContinueTimeout: 1 * time.Second,

}

“So our client and server are HTTP/2-ready? Why they don’t use HTTP/2?”

Yes, both are ready for HTTP/2—but only over HTTPS. For plain HTTP, there’s a missing piece: support for unencrypted HTTP/2. Here’s how you can enable unencrypted HTTP/2 with a quick tweak:

var protocols http.Protocols

protocols.SetUnencryptedHTTP2(true)

// server

server := &http.Server{

Addr: ":8080",

Handler: http.HandlerFunc(rootHandler),

Protocols: &protocols,

}

// client

client := &http.Client{

Transport: &http.Transport{

ForceAttemptHTTP2: true,

Protocols: &protocols,

},

}

// Response: Request Protocol: HTTP/2.0

By enabling unencrypted HTTP/2 with protocols.SetUnencryptedHTTP2(true), the client and server now communicate over HTTP/2, even without HTTPS. It’s a small tweak, but it makes everything click into place.

Interestingly, Go also supports HTTP/2 through the golang.org/x/net/http2 package, which gives you even more control. Here’s an example of setting it up:

// server

h2s := &http2.Server{

MaxConcurrentStreams: 250,

}

h2cHandler := h2c.NewHandler(handler, h2s)

server := &http.Server{

Addr: ":8080",

Handler: h2cHandler,

}

// client

client := &http.Client{

Transport: &http2.Transport{

AllowHTTP: true,

DialTLS: func(network, addr string, cfg *tls.Config) (net.Conn, error) {

return net.Dial(network, addr)

},

},

}

This shows that HTTP/2 doesn’t actually need to rely on TLS, it’s just a protocol that works over the HTTP/1.1 foundation. However, in most cases, if your server already has TLS enabled, the default Go HTTP client will automatically use HTTP/2 and fall back to HTTP/1.1 when needed. No extra steps required.

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem. If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus