- Blog /

- gRPC in Go: Streaming RPCs, Interceptors, and Metadata

gRPC in Go: Streaming RPCs, Interceptors, and Metadata

This article is part of the ongoing gRPC communication protocol series:

- From net/rpc to gRPC in Go Applications

- How HTTP/2 Works and How to Enable It in Go

- Practical Protobuf: From Basic to Best Practices

- How Protobuf Works: The Art of Data Encoding

- gRPC in Go: Streaming RPCs, Interceptors, and Metadata (We’re here)

gRPC is a high-performance RPC framework that uses protobuf for serialization and HTTP/2 for transport. This combo leads to better latency and bandwidth compared to the usual JSON-based APIs.

More details:

Read benchmark results at How Protobuf Works

That said, if network overhead isn’t really a concern, these performance gains might not make a noticeable difference. In such cases, the real advantage of gRPC/protobuf might come from its contract-based design, maintainability, and rich ecosystem rather than raw speed.

Before we get deeper into gRPC, let’s make sure we have the right mental model of where we are:

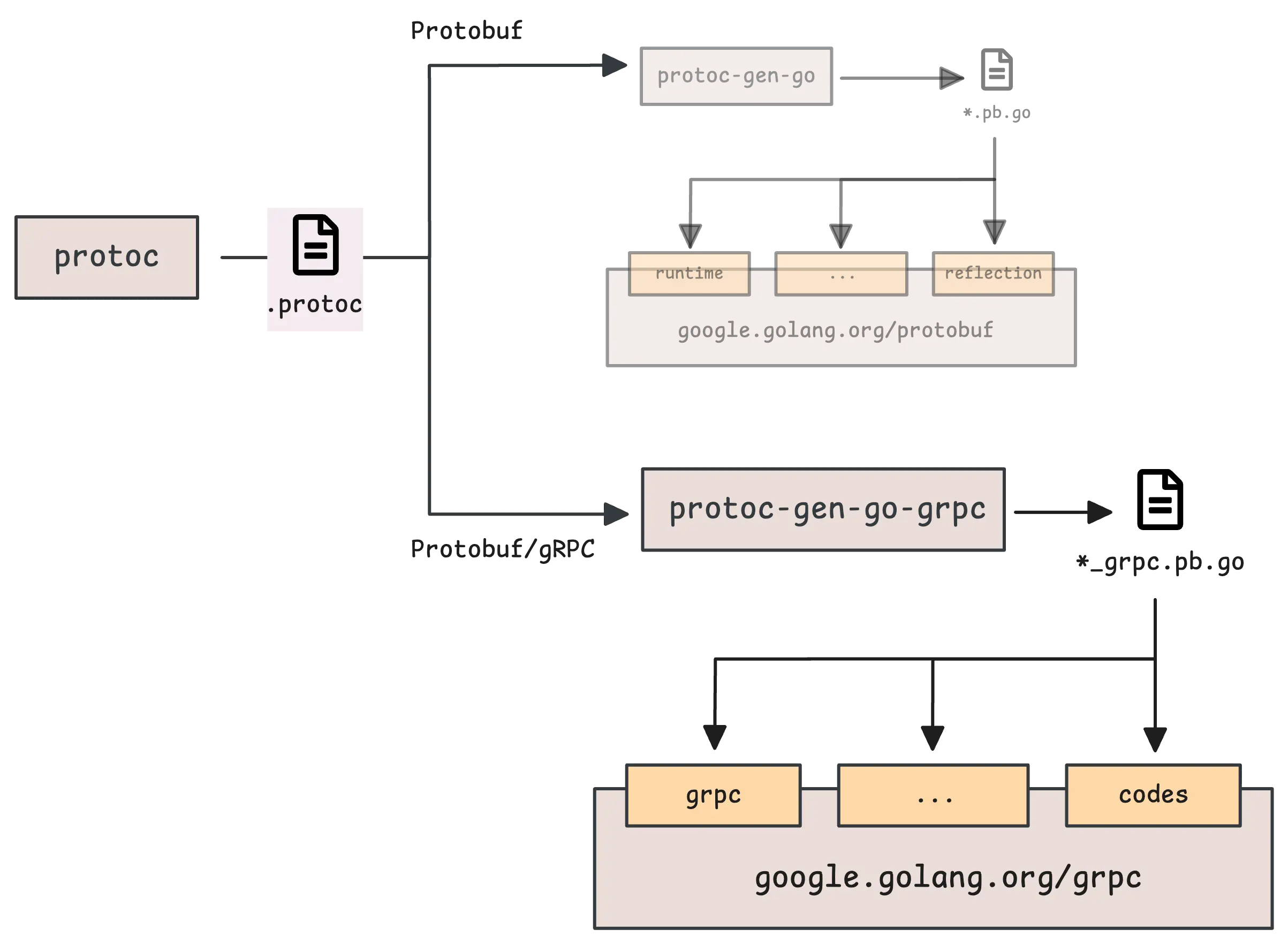

The protoc tool itself is just a protobuf compiler—it doesn’t generate Go code on its own. Instead, it depends on plugins that handle language-specific code generation. Each plugin takes care of a different part of that process.

In previous articles, we covered the first plugin, protoc-gen-go. Now it’s time for the second one: protoc-gen-go-grpc.

Understanding gRPC Commands

#

Let’s start with a simple service called Echo. It takes any string and returns the same string, but with a “Echo: “ prefix.

syntax = "proto3";

option go_package = ".;echo";

service Echo {

rpc EchoMessage (EchoRequest) returns (EchoReply) {}

}

message EchoRequest {

string message = 1;

}

message EchoReply {

string message = 1;

}

In the service definition, every rpc method must have exactly 1 input parameter and 1 output parameter, both wrapped inside message types.

So even if our input is just a plain string, we still need to wrap it inside a message. And if an RPC method needs multiple inputs, they all get bundled into a single message as well.

Now, what if an RPC method doesn’t need any input? The usual approach is to use an empty message. gRPC already provides a predefined one: google.protobuf.Empty.

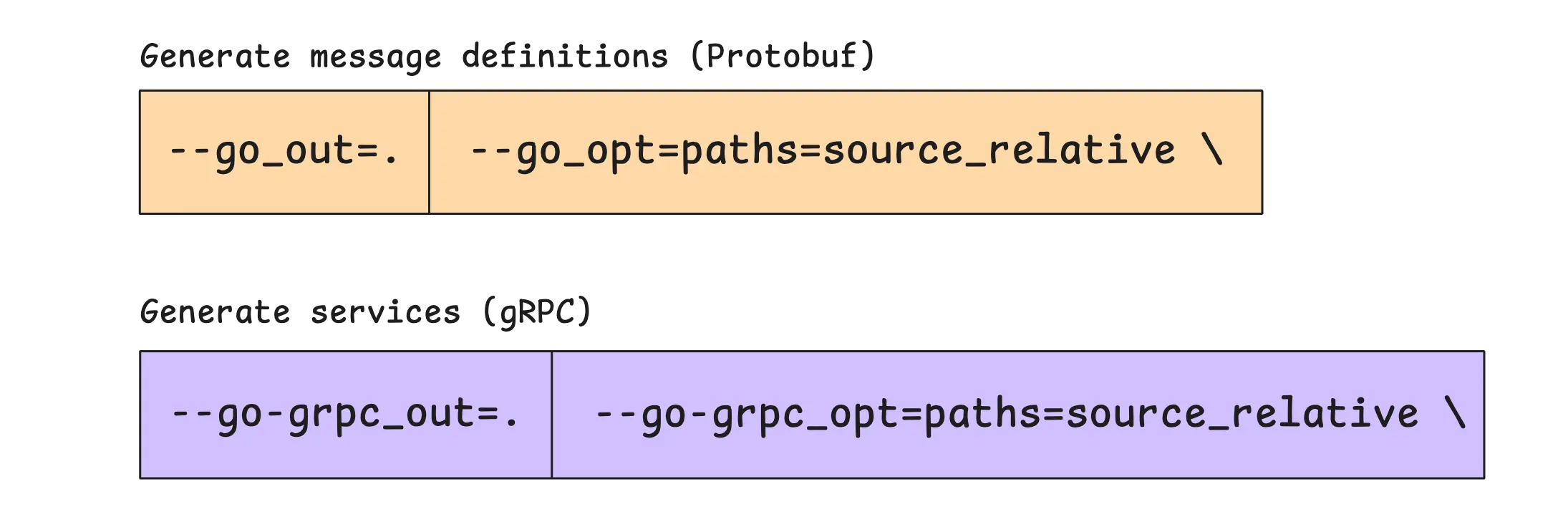

To generate the gRPC code, run this command:

protoc --go_out=. --go_opt=paths=source_relative \

--go-grpc_out=. --go-grpc_opt=paths=source_relative \

echo.proto

This command actually does two separate things, each handled by a different plugin:

protoc-gen-goplugin: Generates Go code for the protobuf message definitions, placing them in the current directory (.).protoc-gen-go-grpcplugin: Generates additional Go code for the gRPC service definitions—this includes server-side interfaces, client stubs, and methods required to interact with gRPC services.

The result is two different Go files: echo.pb.go and echo_grpc.pb.go. One handles protobuf messages, the other handles gRPC service logic.

The paths=source_relative Option

#

Now, let’s talk about the part that often causes confusion: the paths=source_relative option.

When you run protoc with the Go plugin, the compiler looks at this line in your .proto file:

option go_package = ".;echo";

This option follows a specific format, where two parts are separated by a semicolon:

option go_package = "full/import/path;packagename";

This does two things:

- It decides where the generated files go.

- It defines what Go package name is used in the generated files (

package <packagename>). If the package name is left out (everything after;), protobuf automatically picks the last segment of the path as the package name.

Without any extra options in the command, protoc places the generated files inside directories matching the import path:

$ protoc --go_out=. --go-grpc_out=. proto/echo.proto

The result looks like this:

├── full

│ └── import

│ └── path

│ ├── echo.pb.go

│ └── echo_grpc.pb.go

└── proto

└── echo.proto

protoc builds this directory structure based on full/import/path, starting from the location specified in --go_out (and --go-grpc_out).

With paths=source_relative, the compiler skips that and just places the generated files right next to the .proto file instead of following the import path in go_package.

├── proto

│ ├── echo.proto

│ ├── echo.pb.go

│ └── echo_grpc.pb.go

So, if you want the generated code to use package echo, you have two options:

// Option 1:

option go_package = ".;echo";

// Option 2:

option go_package = "whatever/path/you/want/echo";

Both work, but the choice depends on how you want to organize your code.

gRPC Generated Code

#

Implementing a gRPC Server

#

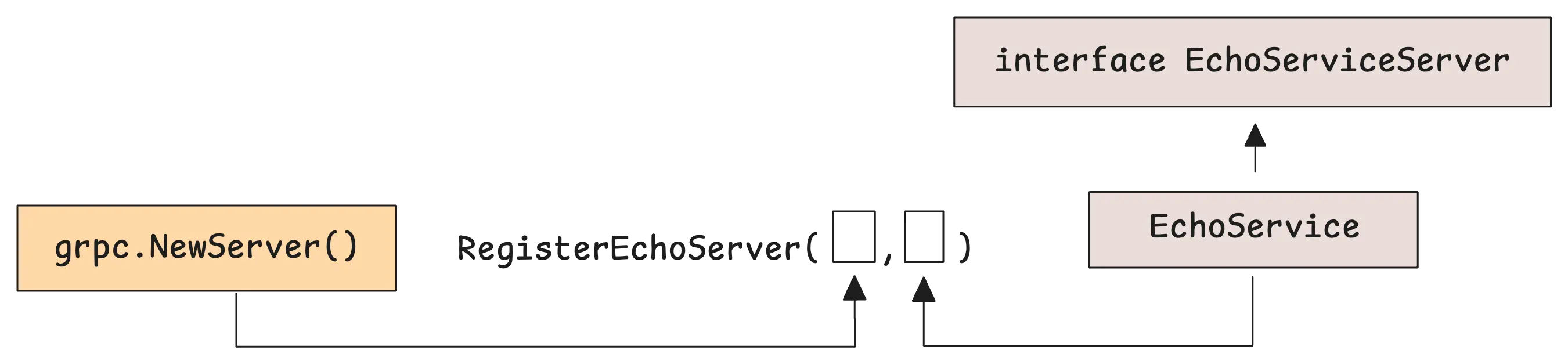

The gRPC plugin generates code that serves as a foundation for both the server and client sides of your service. But when you’re working on the server side, there are really just two things that matter:

- An interface that defines the methods of the service. Your implementation will need to satisfy this interface:

type EchoServiceServer interface {

Echo(context.Context, *EchoRequest) (*EchoResponse, error)

mustEmbedUnimplementedEchoServer()

}

- A function to register your implementation with the gRPC server:

func RegisterEchoServer(s grpc.ServiceRegistrar, srv EchoServer) {

...

s.RegisterService(&Echo_ServiceDesc, srv)

}

At this point, all that’s left is to create an implementation of EchoServer and register it with the gRPC server.

type EchoService struct {

UnimplementedEchoServer

}

func (s *EchoService) EchoMessage(ctx context.Context, req *EchoRequest) (*EchoReply, error) {

return &EchoReply{Message: "Echo: " + req.Message}, nil

}

func main() {

lis, _ := net.Listen("tcp", ":9191")

server := grpc.NewServer()

RegisterEchoServer(server, &EchoService{})

server.Serve(lis)

}

And just like that, you now have a working gRPC server that handles Echo requests. You can even test it right away using grpcurl:

$ grpcurl -plaintext -d '{"message": "Hello from grpcurl"}' -proto echo.proto localhost:9191 Echo/EchoMessage

{

"message": "Echo: Hello from grpcurl"

}

One thing to keep in mind—error handling is left out here for clarity, unless it’s directly related to gRPC itself.

Unimplemented & Unsafe

#

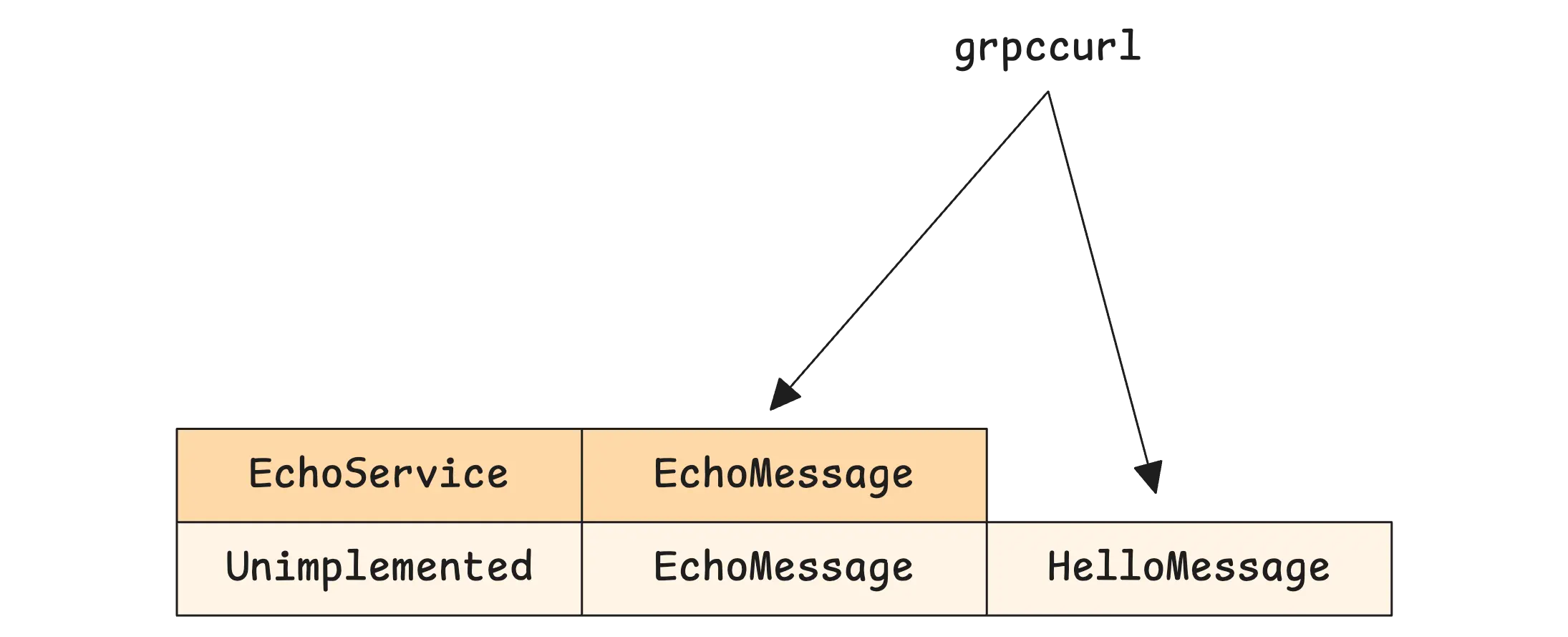

The EchoServer interface requires every implementation to include the odd-looking mustEmbedUnimplementedEchoServer() method. This happens automatically when you embed UnimplementedEchoServer in your struct.

It serves an important purpose: forward compatibility.

Imagine a new method, HelloMessage, gets added to the .proto file. If your implementation doesn’t include it, your project won’t compile. That’s where UnimplementedEchoServer steps in—it provides a default method that returns an Unimplemented error, so your service remains functional even if it doesn’t support the new method yet:

func (s *EchoService) HelloMessage(ctx context.Context, req *HelloRequest) (*HelloResponse, error) {

return nil, status.Errorf(codes.Unimplemented, "method HelloMessage not implemented")

}

Now, if someone tries to call HelloMessage, they’ll see this:

$ grpcurl -plaintext -d '{"message": "Hello from grpcurl"}' -proto echo.proto localhost:9191 Echo/HelloMessage

ERROR:

Code: Unimplemented

Message: method HelloMessage not implemented

Since struct embedding automatically wires everything up, it works seamlessly in the background.

There’s another way to handle this. Instead of using UnimplementedEchoServer, you could opt for UnsafeEchoServer:

type EchoService struct {

UnsafeEchoServer

}

This means you’re taking full responsibility—if a new method is added in the future, you have to define it yourself.

“Unsafe” doesn’t mean it will cause crashes or runtime panics. Instead, it introduces strict compile-time checks. If the .proto file changes and your service is missing a required method, the Go compiler will complain when you try to register your service, stopping everything until it’s fixed.

Metadata

#

Metadata in gRPC is just extra information attached to requests and responses. It doesn’t belong in the main protobuf-defined messages—you can think of it like HTTP headers.

Question!

“Why not just put this extra data inside the protobuf message itself?”

That’s a separation of concerns issue. Messages handle business logic, while metadata carries contextual information that helps process the request without changing the core message structure. If every request needed an authorization token, for example, you wouldn’t want to modify every message type just to include it.

Metadata is useful for things like security tokens (JWT), rate-limiting headers, request tracing, and logging identifiers.

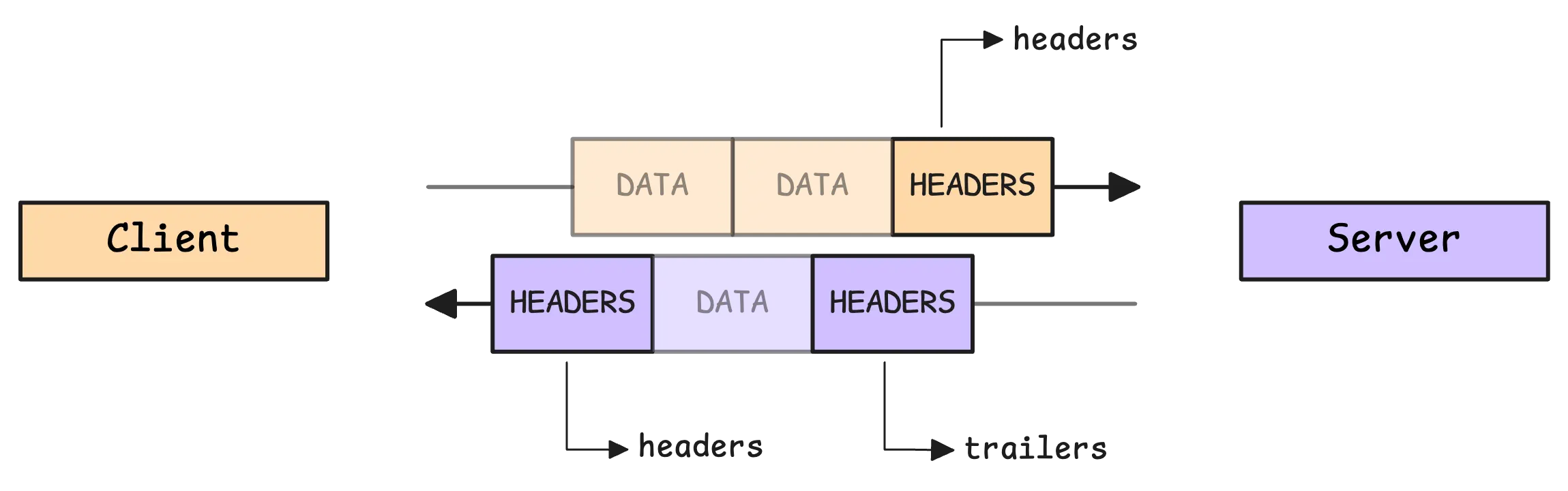

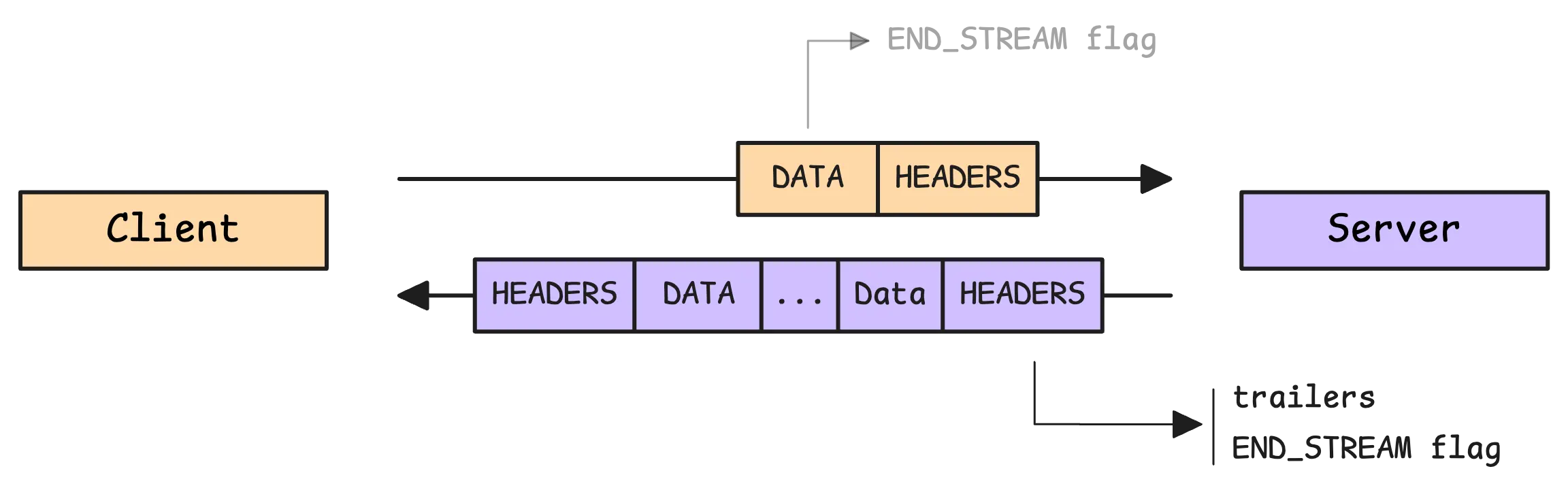

There are two types: headers and trailers.

Headers

#

Headers are metadata sent at the start of the request or response. To see how this works, it helps to recall how HTTP/2 streams data: How HTTP/2 Works and How to Enable It in Go

Here’s a simplified version of the flow:

- A gRPC stream always begins with an HTTP/2

HEADERSframe that includes pseudo-headers and custom headers. - The message payload is sent afterward in one or more

DATAframes. - The stream ends with another

HEADERSframe (with theEND_STREAMflag) containing response trailers.

Since headers go out first, they’re often used for things like authorization tokens, tracing IDs, or anything else the server needs to know before handling the request.

Metadata is stored as key-value pairs, where the key is a case-insensitive string and the value is a slice of strings:

type Metadata map[string][]string

Clients attach metadata to a request using the request context:

func main() {

...

// Prepare metadata

md := metadata.Pairs(

"authorization", "Bearer my-secret-token",

)

ctx := metadata.NewOutgoingContext(context.TODO(), md)

// Call RPC

var header metadata.MD

client := NewEchoClient(conn)

response, _ := client.EchoMessage(

ctx,

request,

grpc.Header(&header), // Receives headers from the server

)

}

Instead of NewOutgoingContext, AppendToOutgoingContext is the recommended way since it merges new metadata with any existing metadata in the context.

Once attached, metadata travels with the request and is converted to HTTP/2 headers in the initial HEADERS frame. Notice that, the example above also shows how client can receive headers from the server.

On the server side, the process is reversed:

func (s *EchoService) EchoMessage(ctx context.Context, req *EchoRequest) (*EchoReply, error) {

// Receive headers from the client

md, ok := metadata.FromIncomingContext(ctx)

if ok {

fmt.Printf("headers: %v\n", md)

}

// Set headers

header := metadata.Pairs(

"received-at", time.Now().Format(time.RFC3339),

)

_ = grpc.SetHeader(ctx, header)

return &EchoReply{Message: "Echo: " + req.GetMessage()}, nil

}

// Output:

// headers: map[:authority:[localhost:9191] authorization:[Bearer my-secret-token]

// content-type:[application/grpc] user-agent:[grpc-go/1.71.0]]

The server extracts headers from the request context and can also attach its own metadata to the response.

Calling grpc.SetHeader multiple times merges new headers with existing ones. These headers are then automatically sent in the HEADERS frame before the response. If grpc.SendHeader() is called explicitly, all previously set headers are sent immediately, along with any extra ones provided.

One last thing, metadata keys are case-insensitive. Everything is converted to lowercase before being sent.

Trailers

#

Trailers are metadata sent after the main response has been fully transmitted. They’re usually used for information that’s only available once processing is complete—things like checksums, extra debugging details, or any final bits of data that don’t belong in the main response.

Now, trailers are only sent by the server. The client doesn’t send them because it doesn’t include a HEADERS frame at the end like the server does. They appear in the final HTTP/2 HEADERS frame after the response is complete.

Setting trailers is done in the same way as headers:

func (s *EchoService) EchoMessage(ctx context.Context, req *EchoRequest) (*EchoReply, error) {

...

// Set trailers

defer func(t time.Time) {

_ = grpc.SetTrailer(ctx, metadata.Pairs("response-time", time.Since(t).String()))

}(time.Now())

return &EchoReply{Message: "Echo: " + req.GetMessage()}, nil

}

Trailers are automatically sent when the RPC completes. It’s not the defer statement that makes this happen—you can set them anywhere in the handler.

Now, there’s a small difference between headers and trailers.

For headers, gRPC provides both grpc.SetHeader() and grpc.SendHeader(), which gives control over when headers are sent. But for trailers, there’s only grpc.SetTrailer(). The gRPC framework decides when they go out.

On the client side, receiving trailers works the same way as receiving headers:

func main() {

...

var trailer metadata.MD

client := NewEchoClient(conn)

response, _ := client.EchoMessage(

ctx,

request,

grpc.Trailer(&trailer), // Receives trailers

)

}

So far, so good. Metadata plays really well with interceptors, but before we dive into that, let’s take a look at streaming.

Streaming

#

Sending a massive payload in a single RPC call can slow things down and waste resources. Plus, traditional RPC isn’t built for real-time communication or continuous updates.

gRPC solves this with streaming, which lets both the client and server send multiple messages over a single connection.

There are three types of streaming, and it all comes down to where you put the stream keyword.

Server Streaming

#

In server streaming, the client sends one request, and the server responds with a series of messages instead of a single response.

To set up a server streaming RPC, the stream keyword goes in front of the response type:

rpc EchoServerStreaming(MyRequest) returns (stream MyResponse);

The client kicks things off with a request, then reads responses one by one until the server signals that it’s done sending messages:

func main() {

...

// Call the server streaming RPC

request := &EchoRequest{Message: "Hello from client!"}

stream, _ := client.EchoServerStreaming(ctx, request)

// Receive and process responses

for {

response, err := stream.Recv()

if err == io.EOF {

break

}

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("error while receiving: %v", err)

}

// Process the response

fmt.Printf("Received: %s\n", response.GetMessage())

}

// Retrieve trailers after the stream closes

fmt.Printf("trailers: %v\n", stream.Trailer())

}

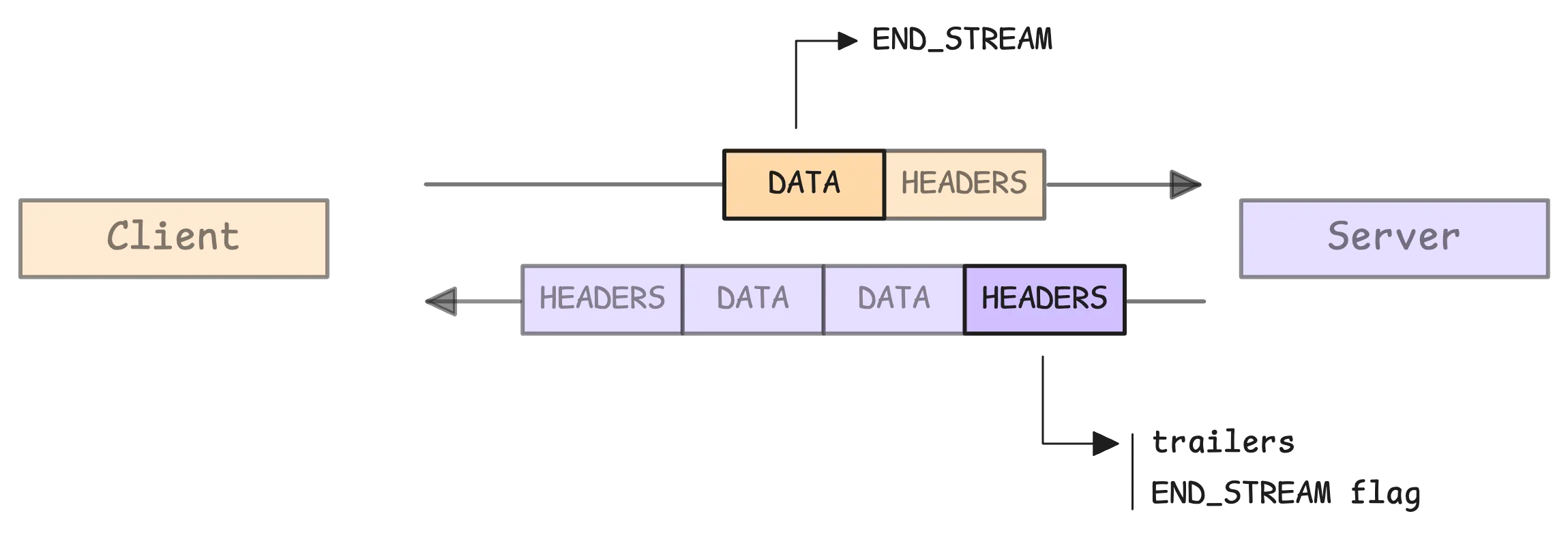

Once the client sends its request, it’s included the payload in the DATA frame, and the END_STREAM flag is set immediately.

One important thing about server streaming (and bidirectional streaming)—the stream.Trailer() method should only be called after the stream has ended. That means waiting until stream.Recv() returns an error, including io.EOF.

This isn’t just a gRPC rule—it’s tied to how HTTP/2 handles trailers. gRPC waits until the last message is sent before delivering them.

When the server finishes sending all messages, the client detects this by receiving an io.EOF error. That doesn’t mean the server itself has to return io.EOF, gRPC takes care of that.

On the server side, the request comes in, the response is assembled, and messages are streamed back one by one:

func (s *EchoService) EchoServerStreaming(req *EchoRequest, stream Echo_EchoServerStreamingServer) error {

msg := req.GetMessage()

result := "Echo: " + msg

for i := 0; i < len(result); i++ {

_ = stream.Send(&EchoReply{Message: string(result[i])})

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}

return nil

}

This server sends back one character at a time, pausing for a second between each message. Calling stream.Send() repeatedly keeps the stream open until the function returns.

While working with streaming, you might notice the stream.RecvMsg() and stream.SendMsg() methods. These are part of gRPC’s internal mechanics. It’s recommended to avoid calling them directly, and stick to stream.Send() and stream.Recv() since they provide type safety.

Obviously, there are only two ways to close a stream:

- Return

nilto indicate a successful completion. - Return an error, signaling a failure with a specific gRPC status code from the

statusandcodespackages.

Once the server completes a stream successfully, gRPC sends an HTTP/2 frame with the END_STREAM flag, just like the client does. END_STREAM is how HTTP/2 signals that no more data will be sent on that stream. On the client side, the transport layer (of client) translates this into an io.EOF error.

Not familiar with HTTP/2? Check out How HTTP/2 Works and How to Enable It in Go

There are five common cases to keep in mind when handling errors in gRPC:

- Standard errors like

fmt.Errorf("something went wrong")get mapped tocodes.Unknown. - Context errors (from the

contextpackage) are mapped to eithercodes.Canceledorcodes.DeadlineExceeded, depending on what caused the failure. - I/O errors (from the

iopackage) have special handling—io.EOFremains unchanged, whileio.ErrUnexpectedEOFgets mapped tocodes.Internal. - HTTP/2 stream errors are mapped to corresponding gRPC errors based on the HTTP/2 error code. This table shows the exact mappings.

- Errors that implement the

GRPCStatus()method remain unchanged.

These rules don’t just apply to streaming RPCs—they work the same way in unary RPCs as well.

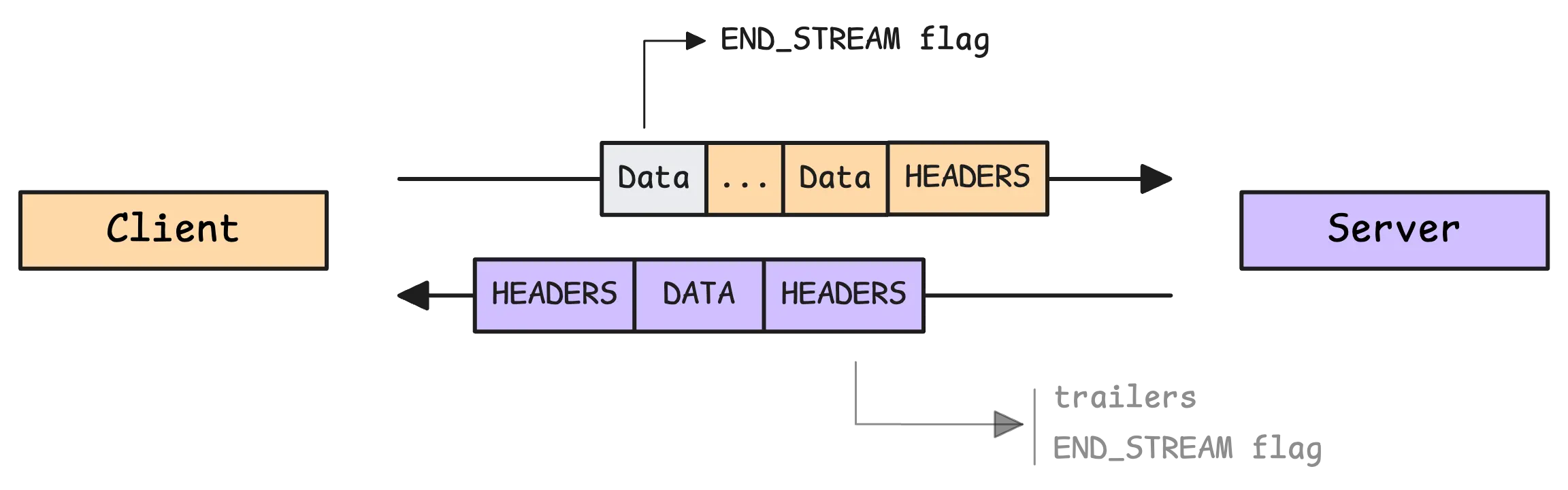

Client Streaming

#

In client streaming, the client sends multiple messages over a stream and waits for a single response from the server.

To define a client streaming RPC, the stream keyword goes before the request type:

rpc EchoClientStreaming(stream MyRequest) returns (MyResponse);

Now, how does the server know when the client is done sending messages?

In server streaming, the server signals completion by returning nil (or an error) from the RPC handler. But in client streaming, the client doesn’t have a function to explicitly ’end’ the request.

Instead of Recv() and Send(), client streaming has its own gears: CloseAndRecv on the client side and SendAndClose on the server side.

Here’s how it looks on the client:

func main() {

...

// Call the client streaming RPC

stream, _ := client.EchoClientStreaming(context.TODO())

// Send messages to the server

for _, msg := range "Hello from client!" {

_ = stream.Send(&EchoRequest{Message: string(msg)})

}

// Close the stream and receive the response

reply, _ := stream.CloseAndRecv()

// Process the response

fmt.Printf("Received: %s\n", reply.GetMessage())

}

Calling CloseAndRecv() sends an empty DATA frame with the END_STREAM flag, letting the server know that the client is finished sending messages.

On the server side, the END_STREAM flag translates into an io.EOF error when reading from the stream.

func (s *EchoService) EchoClientStreaming(stream Echo_EchoClientStreamingServer) error {

msg := ""

for {

req, err := stream.Recv()

if err == io.EOF {

break

}

if err != nil {

return err

}

msg += req.GetMessage()

}

return stream.SendAndClose(&EchoReply{Message: "Echo: " + msg})

}

Once all messages are received, the server responds with SendAndClose(), sending the final response and closing the stream at the same time.

Just like before, stream.RecvMsg() and stream.SendMsg() exist, but they’re part of gRPC’s internals. Stick to what we’ve done in these examples—they’re the recommended way to work with streaming RPCs.

Bidirectional Streaming

#

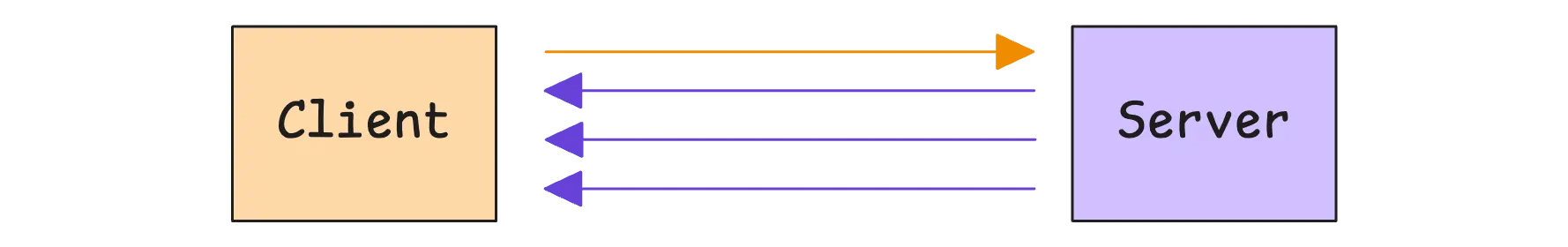

In bidirectional streaming, both the client and server send messages independently. Neither side has to wait for the other, which makes this perfect for real-time communication—things like chat apps, live updates, or long-running tasks.

To set this up, the stream keyword goes in front of both the request and response types:

rpc EchoBidirectionalStreaming(stream MyRequest) returns (stream MyResponse);

Typically, both the client and server handle sending and receiving in separate goroutines. One keeps sending messages, while the other continuously calls Recv() to read incoming data from the stream.

The client side gets a little more verbose:

func main() {

...

stream, _ := client.EchoBidirectionalStreaming(ctx)

// Start a goroutine to receive messages

waitc := make(chan struct{})

go func() {

defer close(waitc)

for {

resp, err := stream.Recv()

if err == io.EOF {

break

}

if err != nil {

break // Handle error

}

fmt.Printf("Received: %s\n", resp.GetMessage())

}

}()

// Send messages

for _, msg := range "Hello from client!" {

_ = stream.Send(&EchoRequest{Message: string(msg)})

}

// Signal that we're done sending

stream.CloseSend()

<-waitc

}

This example keeps things straightforward, but the receiving loop could also spawn new goroutines to handle incoming messages. That way, Recv() can keep pulling data from the stream without waiting for message processing to complete.

On the server side:

func (s *EchoService) EchoBidirectionalStreaming(stream Echo_EchoBidirectionalStreamingServer) error {

for {

req, err := stream.Recv()

if err == io.EOF {

// Client has finished sending

return nil

}

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Process the request and prepare a response

res := &EchoReply{

Message: "Echo: " + req.GetMessage(),

}

_ = stream.Send(res)

}

}

And that’s how bidirectional streaming works.

Question!

“Does the server always receive messages in order? Could it process ’e’ before ‘H’ and send responses out of order?”

Good news—this won’t happen. The server receives messages in the exact order they were sent: ‘H’, ’e’, ’l’, ’l’, ‘o’, and so on.

This is guaranteed by the HTTP/2 protocol, which gRPC uses as its transport layer. More details are covered in How HTTP/2 Works and How to Enable It in Go.

However, this example doesn’t fully unlock the power of bidirectional streaming.

Even though the client sends and receives messages at the same time, the flow still follows a structured back-and-forth exchange—more like request-response rather than fully independent event-driven communication.

The real advantage is that the server can push messages anytime without waiting for client requests. This opens up real-time features like notifications, broadcasts, and status updates while keeping the connection open for as long as needed.

Interceptor

#

The term “middleware” is common in web frameworks like Express.js or Gin, but in gRPC, the equivalent concept is called an “interceptor.” Same general idea, though there are some key differences.

Interceptors let you step into the execution flow of RPC calls, allowing you to modify or inspect requests and responses before they reach your service logic. This makes them great for things like authentication, logging, monitoring, rate limiting, and error handling—without touching your core implementation.

There are two sides (server and client) and two modes (unary and streaming), which gives us four types of interceptors:

- Unary server interceptor

- Stream server interceptor

- Unary client interceptor

- Stream client interceptor

Each has a slightly different function signature, so we’ll go through them one by one.

Unary Interceptor Examples

#

A unary server interceptor intercepts unary RPCs on the server side:

func LoggingUnaryInterceptor(ctx context.Context, req any, info *grpc.UnaryServerInfo, handler grpc.UnaryHandler) (any, error) {

start := time.Now()

fmt.Printf("Request: method=%s\n", info.FullMethod)

// Call the actual RPC method

resp, err := handler(ctx, req)

fmt.Printf("Response: method=%s duration=%s error=%v\n",

info.FullMethod, time.Since(start), err)

return resp, err

}

grpc.NewServer(

grpc.UnaryInterceptor(LoggingUnaryInterceptor),

)

Here’s what happens when a unary RPC request comes in:

- The server receives the request, identifies the method, and unmarshals the request message.

- If a unary interceptor is registered, the server calls it before running the actual RPC method.

- The interceptor does its pre-processing (like logging), then calls

handler()to run the RPC method. - Once the

handler()returns, the interceptor does any post-processing before sending the response. - The final response and any errors are passed back to the client.

A unary client interceptor steps in on the client side for unary (request-response) RPCs. It can modify requests, inspect responses, or retry failed calls before returning a final result to the caller:

func RetryUnaryInterceptor(ctx context.Context, method string, req, reply any, cc *grpc.ClientConn, invoker grpc.UnaryInvoker, opts ...grpc.CallOption) error {

maxRetries := 3

for attempt := 0; attempt < maxRetries; attempt++ {

err := invoker(ctx, method, req, reply, cc, opts...)

if err == nil || !isRetryable(err) {

return err

}

fmt.Printf("Retrying %s, attempt %d after error: %v\n", method, attempt+1, err)

}

return invoker(ctx, method, req, reply, cc, opts...)

}

func isRetryable(err error) bool {

code := status.Code(err)

return code == codes.Unavailable || code == codes.DeadlineExceeded

}

grpc.NewClient(

"localhost:50051",

grpc.WithUnaryInterceptor(RetryUnaryInterceptor),

)

In unary client calls, the response gets written directly into the reply parameter. The interceptor’s job is to call the invoker, which fills in reply and returns any error that occurred. This example retries failed requests if the error is Unavailable or DeadlineExceeded.

Streaming Interceptor Examples

#

Now, let’s look at stream server interceptors. These are similar but work with streaming RPCs. The real power of interceptors shows up when combined with metadata:

func AuthInterceptor(srv any, ss grpc.ServerStream, info *grpc.StreamServerInfo, handler grpc.StreamHandler) error {

// Skip authentication for public methods

if !info.IsClientStream && strings.HasPrefix(info.FullMethod, "/api.public.") {

return handler(srv, ss)

}

// Require authentication for everything else

md, ok := metadata.FromIncomingContext(ss.Context())

if !ok || len(md["token"]) == 0 {

return status.Errorf(codes.Unauthenticated, "method %s requires authentication", info.FullMethod)

}

// Proceed with the RPC

return handler(srv, ss)

}

This interceptor checks the request metadata before deciding whether to allow the request. If the request targets a public API (/api.public.*), it skips authentication. Otherwise, it looks for a token in the metadata and rejects the request if one isn’t found.

One important thing—unlike middleware in web frameworks, interceptors in gRPC apply globally. That means you can’t enable authentication selectively for specific RPC methods. Instead, the usual approach is to inspect the request metadata and decide dynamically whether authentication is required.

Next, we have stream client interceptors, which intercept streaming RPCs before the client starts sending messages:

func TimeoutStreamInterceptor(ctx context.Context, desc *grpc.StreamDesc, cc *grpc.ClientConn, method string, streamer grpc.Streamer, opts ...grpc.CallOption) (grpc.ClientStream, error) {

timeoutCtx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 5*time.Second)

defer cancel()

stream, err := streamer(timeoutCtx, desc, cc, method, opts...)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to create %s stream: %w", desc.StreamName, err)

}

// Return the stream with timeout applied

return stream, nil

}

This example wraps streaming RPCs with a five-second timeout. If the stream takes too long to initialize, it fails immediately instead of hanging indefinitely.

Takeaways

#

Interceptors unlock a lot of flexibility in gRPC. Here are the takeaways from these examples:

- Unary server interceptor: The interceptor runs before and after the RPC method. You can log, modify, or replace responses before they reach the client.

- Unary client interceptor: The interceptor gets control before sending the request and after receiving the response. The

replyobject is owned by the client, so you must modify it directly. - Stream server interceptor: The gRPC framework owns the stream, but you can wrap the

ServerStreamto modify the context before it reaches the handler. - Stream client interceptor: The interceptor creates and returns the stream. You can wrap

ClientStreamto intercept operations likeSend()andRecv().

The last two points bring up the next question: how do you intercept every message in a stream?

Intercept Every Message in the Stream

#

So far, the interceptors we’ve covered only step in when the stream is created. But what if you need to intercept every message sent or received within that stream?

For server-side streaming, the key is to intercept each stream.SendMsg() call, since that’s what gets triggered repeatedly.

To do this, we need to wrap the original stream and override SendMsg():

type wrappedServerStream struct {

grpc.ServerStream

}

func (w *wrappedServerStream) SendMsg(m interface{}) error {

fmt.Printf("Intercepted server Send: %v\n", m)

// Call the original Send method

return w.ServerStream.SendMsg(m)

}

Thanks to Go’s embedding, this new method (SendMsg) will shadow the original, so every outgoing message passes through it.

Question!

“Didn’t you say not to use stream.RecvMsg() and stream.SendMsg() directly?”

Yes, when you intercept SendMsg, you are intercepting at a lower level where the actual message serialization and transmission happen. This is the right approach because all Send() calls will eventually go through SendMsg().

We just need to wrap the stream inside the interceptor and pass it to the handler:

func streamServerInterceptor(srv interface{}, ss grpc.ServerStream, info *grpc.StreamServerInfo, handler grpc.StreamHandler) error {

wrappedStream := &wrappedServerStream{

ServerStream: ss,

}

return handler(srv, wrappedStream)

}

On the client side, it’s the same idea, except we’re intercepting RecvMsg(). This works for both individual stream.Recv() calls and the final stream.SendAndClose(). The approach is identical; wrap the stream, override the methods and create an interceptor to pass it to the handler.

Interceptor Chain

#

When setting up a gRPC server, you’ll often want multiple interceptors:

server := grpc.NewServer(

grpc.UnaryInterceptor(unaryInterceptor1),

grpc.StreamInterceptor(streamInterceptor1),

grpc.UnaryInterceptor(unaryInterceptor2),

grpc.StreamInterceptor(streamInterceptor2),

)

This won’t work. gRPC only allows one UnaryInterceptor and one StreamInterceptor. Trying to register multiple directly like this will cause a panic.

Instead, you need to use the chain version:

server := grpc.NewServer(

grpc.ChainStreamInterceptor(

streamInterceptor1,

streamInterceptor2,

),

grpc.ChainUnaryInterceptor(

unaryInterceptor1,

unaryInterceptor2,

),

)

Order matters here. The first interceptor in the chain is the outermost, wrapping everything else. The last one is the innermost, closest to the actual handler.

If you have a chain [A, B, C], the execution order looks like this:

A starts

B starts

C starts

Handler executes

C finishes

B finishes

A finishes

If any interceptor in the chain returns an error, execution stops immediately, and the error propagates back.

You can also mix chained and non-chained interceptors:

server := grpc.NewServer(

grpc.ChainStreamInterceptor(

streamInterceptor1,

streamInterceptor2,

),

grpc.ChainStreamInterceptor(

streamInterceptor3,

),

grpc.StreamInterceptor(streamInterceptor4),

)

Now, can you guess the execution order?

The interceptors will run in this order:

streamInterceptor4 -> streamInterceptor1 -> streamInterceptor2 -> streamInterceptor3

This is because any standalone interceptors (StreamInterceptor) run first, followed by the ones inside ChainStreamInterceptor, in the order they were added.

Community Interceptors: go-grpc-middleware

#

The go-grpc-middleware package comes with a full set of pre-built gRPC interceptors, so you don’t have to build everything from scratch.

On the server side, it provides interceptors for authentication, logging, panic recovery, rate limiting, request validation, and even selective interceptor application.

- Auth interceptor: Lets you define custom authentication logic using an

AuthFunc. - Recovery interceptor: Catches panics and turns them into proper gRPC errors.

- Validator and protovalidate interceptors: Automatically validate incoming messages based on protobuf definitions.

- Rate limit interceptor: Controls request rates to prevent overload.

- Selector interceptor: Applies specific interceptors only to certain RPC methods.

On the client side, you get interceptors for retries, timeouts, logging, and metrics:

- Retry interceptor: Retries failed requests based on response codes.

- Timeout interceptor: Ensures RPC calls don’t hang indefinitely.

- Logging interceptors: Available for both client and server, with support for popular logging libraries like zap, logrus, and slog.

For monitoring, go-grpc-middleware integrates with Prometheus, providing both client and server metrics. It also plays well with OpenTelemetry for distributed tracing and additional metrics.

And there you have it—everything you need to know about gRPC. Solid effort!

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem. If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Golang Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus