- Blog /

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

The classic Golang array and slice are pretty straightforward. Arrays are fixed-size, and slices are dynamic. But I’ve got to tell you, Go might seem simple on the surface, but it’s got a lot going on under the hood.

As always, we’ll start with the basics and then dig a bit deeper. Don’t worry, arrays get pretty interesting when you look at them from different angles.

We’ll cover slices in the next part, I’ll drop that here once it’s ready., it’s already published: Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home.

What is an array?

#

Arrays in Go are a lot like those in other programming languages. They’ve got a fixed size and store elements of the same type in contiguous memory locations.

This means Go can access each element quickly since their addresses are calculated based on the starting address of the array and the element’s index.

func main() {

arr := [5]byte{0, 1, 2, 3, 4}

println("arr", &arr)

for i := range arr {

println(i, &arr[i])

}

}

// arr 0x1400005072b

// 0 0x1400005072b

// 1 0x1400005072c

// 2 0x1400005072d

// 3 0x1400005072e

// 4 0x1400005072f

There are a couple of things to notice here:

- The address of the array

arris the same as the address of the first element. - The address of each element is 1 byte apart from each other because our element type is

byte.

![Array [5]byte{0, 1, 2, 3, 4} in memory](/blog/go-array/array-5-bytes.webp)

Look at the image carefully.

Our stack is growing downwards from a higher to a lower address, right? This picture shows exactly how an array looks in the stack, from arr[4] to arr[0].

So, does that mean we can access any element of an array by knowing the address of the first element (or the array) and the size of the element? Let’s try this with an int array and unsafe package:

func main() {

a := [3]int{99, 100, 101}

p := unsafe.Pointer(&a[0])

a1 := unsafe.Pointer(uintptr(p) + 8)

a2 := unsafe.Pointer(uintptr(p) + 16)

fmt.Println(*(*int)(p))

fmt.Println(*(*int)(a1))

fmt.Println(*(*int)(a2))

}

// Output:

// 99

// 100

// 101

Well, we get the pointer to the first element and then calculate the pointers to the next elements by adding multiples of the size of an int, which is 8 bytes on a 64-bit architecture. Then we use these pointers to access and convert them back to the int values.

![Array [3]int{99, 100, 101} in memory](/blog/go-array/array-3-ints.webp)

The example is just a play around with the unsafe package to access memory directly for educational purposes. Don’t do this in production without understanding the consequences.

Now, an array of type T is not a type by itself, but an array with a specific size and type T, is considered a type. Here’s what I mean:

func main() {

a := [5]byte{}

b := [4]byte{}

fmt.Printf("%T\n", a) // [5]uint8

fmt.Printf("%T\n", b) // [4]uint8

// cannot use b (variable of type [4]byte) as [5]byte value in assignment

a = b

}

Even though both a and b are arrays of bytes, the Go compiler sees them as completely different types, the %T format makes this point clear.

Here is how the Go compiler sees it internally (src/cmd/compile/internal/types2/array.go):

// An Array represents an array type.

type Array struct {

len int64

elem Type

}

// NewArray returns a new array type for the given element type and length.

// A negative length indicates an unknown length.

func NewArray(elem Type, len int64) *Array { return &Array{len: len, elem: elem} }

The length of the array is “encoded” in the type itself, so the compiler knows the length of the array from its type. Trying to assign an array of one size to another, or compare them, will result in a mismatched type error.

Array literals

#

There are many ways to initialize an array in Go, and some of them might be rarely used in real projects:

var arr1 [10]int // [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]

// With value, infer-length

arr2 := [...]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5} // [1 2 3 4 5]

// With index, infer-length

arr3 := [...]int{11: 3} // [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3]

// Combined index and value

arr4 := [5]int{1, 4: 5} // [1 0 0 0 5]

arr5 := [5]int{2: 3, 4, 4: 5} // [0 0 3 4 5]

What we’re doing above (except for the first one) is both defining and initializing their values, which is called a “composite literal.” This term is also used for slices, maps, and structs.

Now, here’s an interesting thing: when we create an array with less than 4 elements, Go generates instructions to put the values into the array one by one.

So when we do arr := [4]int{1, 2, 3, 4}, what’s actually happening is:

arr := [4]int{}

arr[0] = 1

arr[1] = 2

arr[2] = 3

arr[3] = 4

This strategy is called local-code initialization. This means that the initialization code is generated and executed within the scope of a specific function, rather than being part of the global or static initialization code.

It’ll become clearer when you read another initialization strategy below, where the values aren’t placed into the array one by one like that.

“What about arrays with more than 4 elements?”

The compiler creates a static representation of the array in the binary, which is known as ‘static initialization’ strategy.

This means the values of the array elements are stored in a read-only section of the binary. This static data is created at compile time, so the values are directly embedded into the binary. If you’re curious how [5]int{1,2,3,4,5} looks like in Go assembly:

main..stmp_1 SRODATA static size=40

0x0000 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

0x0010 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

0x0020 05 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ........

It’s not easy to see the value of the array, we can still get some key info from this.

Our data is stored in stmp_1, which is read-only static data with a size of 40 bytes (8 bytes for each element), and the address of this data is hardcoded in the binary.

The compiler generates code to reference this static data. When our application runs, it can directly use this pre-initialized data without needing additional code to set up the array.

const readonly = [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

arr := readonly

“What about an array with 5 elements but only 3 of them initialized?”

Good question, this literal [5]int{1,2,3} falls into the first category, where Go puts the value into the array one by one.

While talking about defining and initializing arrays, we should mention that not every array is allocated on the stack. If it’s too big, it gets moved to the heap.

But how big is “too big,” you might ask.

As of Go 1.23, if the size of the variable, not just array, exceeds a constant value MaxStackVarSize, which is currently 10 MB, it will be considered too large for stack allocation and will escape to the heap.

func main() {

a := [10 * 1024 * 1024]byte{}

println(&a)

b := [10*1024*1024 + 1]byte{}

println(&b)

}

In this scenario, b will move to the heap while a won’t.

Array operations

#

The length of the array is encoded in the type itself. Even though arrays don’t have a cap property, we can still get it:

func main() {

a := [5]int{1, 2, 3}

println(len(a)) // 5

println(cap(a)) // 5

}

The capacity equals the length, no doubt, but the most important thing is that we know this at compile time, right?

So len(a) doesn’t make sense to the compiler because it’s not a runtime property, Go compiler knows the value at compile time. Go takes this key point and turns it into a constant behind the scenes. What the Go compiler sees is:

func main() {

a := [5]int{1, 2, 3}

println(5)

println(5)

}

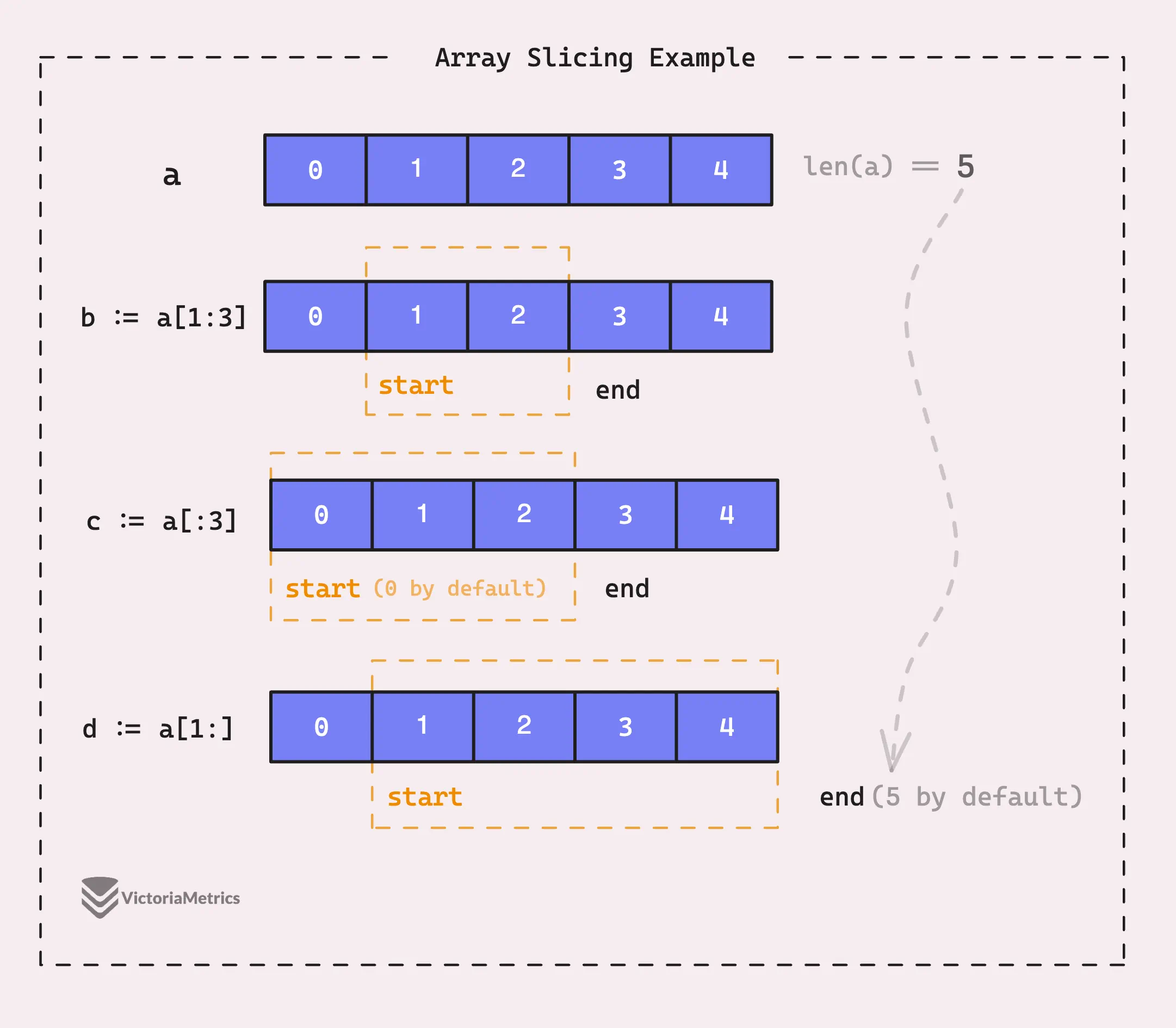

Slicing is a way to get a slice from an array, and its full form is denoted by the syntax [start:end:capacity]. Usually, you’ll see its variants: [start:end], [:end], [start:], [:].

start is the index of the first element to include in the new slice (inclusive), end is the index of the last element to exclude from the new slice (exclusive), and capacity is an optional argument that specifies the capacity of the new slice.

Let’s ignore capacity for now; it will be fully explained in the slice post.

func main() {

a := [5]int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4}

// new slice from a[1] to a[3-1]

b := a[1:3] // [1 2]

// new slice from a[0] to a[3-1]

c := a[:3] // [0 1 2]

// new slice from a[1] to a[5-1]

d := a[1:] // [1 2 3 4]

}

The compiler evaluates the slicing indices (start, end, and capacity) to determine the bounds of the new slice.

If any of the indices are missing, they default to:

startdefaults to 0.enddefaults to the length of the original slice or array,capacitydefaults to the capacity of the original slice or the length of the original array.

“What about the new length and capacity of the slice?”

The new length is determined by subtracting the start index from the end index, and the new capacity is determined by subtracting the start index from either the capacity argument (if provided) or the original capacity.

When we write b := a[1:3], here’s what’s really going on:

b.array = &a[1]

b.len = 3-1

b.cap = 5-1

Regarding the panic when we specify the end index out of bounds: because the end is exclusive, we can specify it to be equal to the length of the original array:

func main() {

a := [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

b := a[4:5] // [4]

}

But, can we specify start at 5, like a[5:]? Take a guess before reading on.

func main() {

a := [5]int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

b := a[5:] // []

}

This might be surprising, the answer is yes.

What we are creating is an empty slice, with no length and no capacity. So, the general rule for bound-checking the slicing is: 0 <= start <= end <= cap <= real capacity.

“But the array underlying b is pointing to a[5], which is out of bounds, right?”

No, Go has special rules to handle this case. The underlying array will still point to a[0], but this slice b is useless.

Array are values, raw values.

#

In some other languages, an array variable is basically a pointer to the first element of the array. When you pass an array to a function, what’s actually passed is a pointer, not the whole array. So, changing the array elements within the function will affect the original array.

In contrast, Go treats arrays as value types. This means an array variable in Go represents the entire array, not just a reference to its first element, even though printing &a gives the same address as &a[0].

When you pass an array to a function in Go, the entire array is copied:

func doSomething(a [5]byte) {

a[0] = 1

}

func main() {

a := [5]byte{}

doSomething(a)

fmt.Println(a)

}

// [0 0 0 0 0]

The output is expected since we’re modifying the copied array, not the original one.

“Isn’t it inefficient? It’s always copied.”

It’s only inefficient if you pass a large array to a function and benchmarks or profilers show it’s a bottleneck. Otherwise, we can just pass arrays as usual.

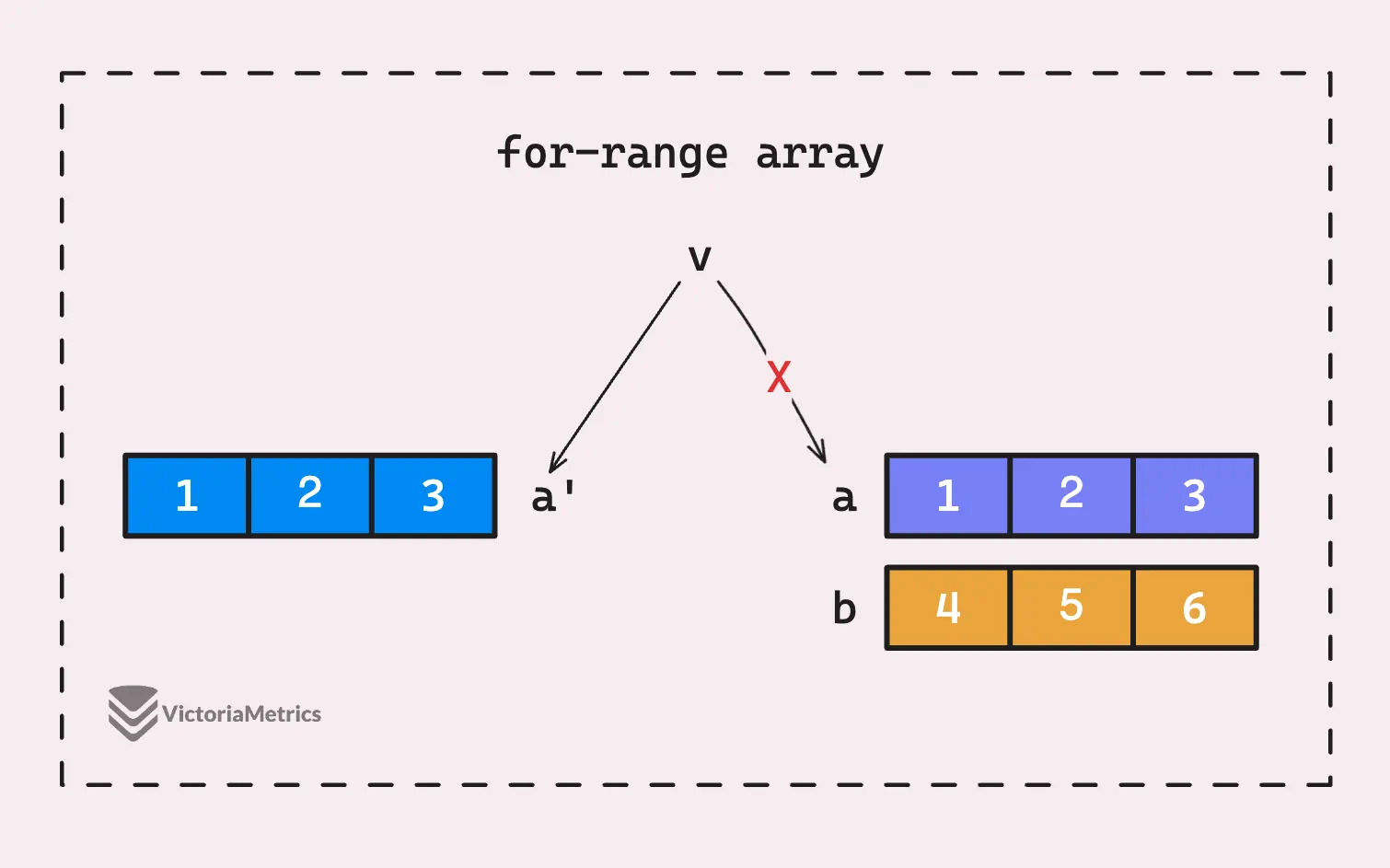

Here’s a tricky thing when you loop over your array, especially using a for-range loop. Let’s start with a quick example:

func main() {

a := [3]int{1, 2, 3}

b := [3]int{4, 5, 6}

for i, v := range a {

if i == 1 {

a = b

}

fmt.Println(v)

}

}

In the snippet, a and b are [3]int so we can assign them, but we assign a = b right in the loop.

So, what’s your guess? I have three options: 1 2 3, 1 5 6, or 1 2 6.

When we iterate to index 1, we immediately change the array, so the output should be 1 2 6, because v already evaluated to 2 before we assign. Unexpectedly, the output is 1 2 3, just like nothing happened. So, did a change, or did our assignment have no effect?

“Oh, the arr used inside the loop is a copy of the original arr, right?”

Good thinking, but that’s only half the truth. Let me explain the rest.

Go indeed makes a copy, but the copy is hidden from us, and only v can see that copied array. The array a we use in the loop is still our original a, and if you print it out after the loop, it’ll be [4 5 6], we could think of another scenario like the one shown below:

Here’s what Go sees:

func main() {

a := [3]int{1, 2, 3}

b := [3]int{4, 5, 6}

a1 := a

for i, v := range a1 {

if i == 1 {

a = b

}

fmt.Println(v)

}

}

Got the idea yet? Only v sees a1, and this is hidden from our perspective as users. This happens even if you don’t assign or change a in the loop.

That means it works like a pass-by-value case. If our array is much bigger than just several elements, making a copy like this will be inefficient and the Go team has optimized this for us by allowing for-range with a pointer to the array.

func main() {

a := [3]int{1, 2, 3}

b := [3]int{4, 5, 6}

for i, v := range &a {

if i == 1 {

a = b

}

fmt.Println(v)

}

}

The output is now 1 2 6, just like we initially expected.

But the key takeaway here isn’t to encourage changing the array inside the loop, I’d not recommend that. Instead, it’s to show that Go supports for-range with a pointer to an array, while it doesn’t support pointers to slices. And now you know why.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Defer: From Basic To Traps

- Go Sync Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- Inside Go’s Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What is it?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.

Leave a comment below or Contact Us if you have any questions!

comments powered by Disqus