The defer statement is probably one of the first things we find pretty interesting when we start learning Go, right?

But there’s a lot more to it that trips up many people, and there’re many fascinating aspects that we often don’t touch on when using it.

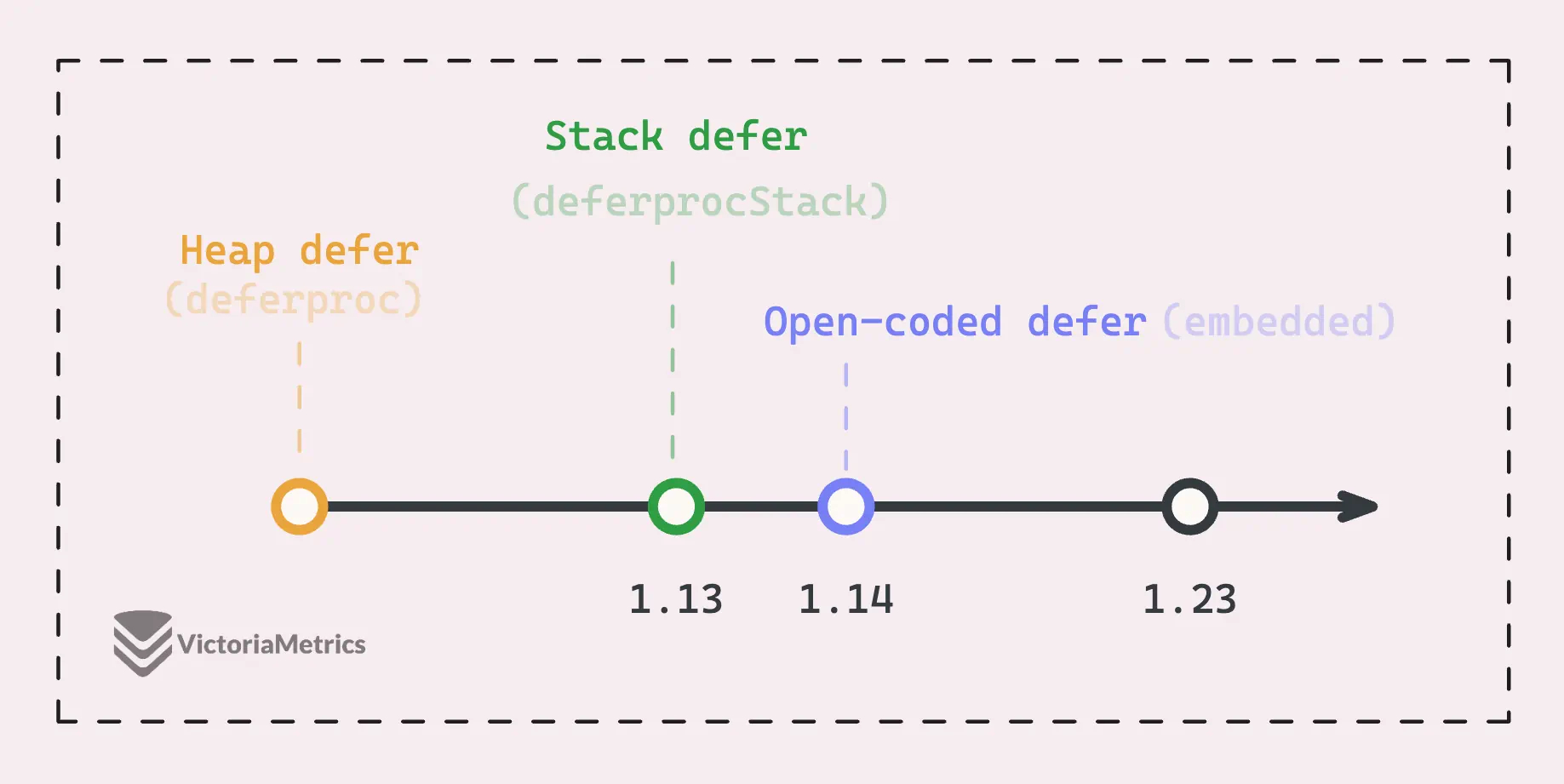

For example, the defer statement actually has 3 types (as of Go 1.22, though that might change later): open-coded defer, heap-allocated defer, and stack-allocated. Each one has different performance and different scenarios where they’re best used, which is good to know if you want to optimize performance.

In this discussion, we’re going to cover everything from the basics to the more advanced usage, and we’ll even dig a bit, just a little bit, into some of the internal details.

What is defer?

#

Let’s take a quick look at defer before we dive too deep.

In Go, defer is a keyword used to delay the execution of a function until the surrounding function finishes.

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("hello")

fmt.Println("world")

}

// Output:

// world

// hello

In this snippet, the defer statement schedules fmt.Println("hello") to be executed at the very end of the main function. So, fmt.Println("world") is called immediately, and “world” is printed first. After that, because we used defer, “hello” is printed as the last step before main finishes.

It’s just like setting up a task to run later, right before the function exits. This is really useful for cleanup actions, like closing a database connection, freeing up a mutex, or closing a file:

func doSomething() error {

f, err := os.Open("phuong-secrets.txt")

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer f.Close()

// ...

}

The code above is a good example to show how defer works, but it’s also a bad way to use defer. We’ll get into that in the next section.

“Okay, good, but why not put the f.Close() at the end?”

There are a couple of good reasons for this:

- We put the close action near the open, so it’s easier to follow the logic and avoid forgetting to close the file. I don’t want to scroll down a function to check if the file is closed or not; it distracts me from the main logic.

- The deferred function is called when the function returns, even if a panic (runtime error) happens.

When a panic happens, the stack is unwound and the deferred functions are executed in a specific order, which we’ll cover in the next section.

Defers are stacked

#

When you use multiple defer statements in a function, they are executed in a ‘stack’ order, meaning the last deferred function is executed first.

func main() {

defer fmt.Println(1)

defer fmt.Println(2)

defer fmt.Println(3)

}

// Output:

// 3

// 2

// 1

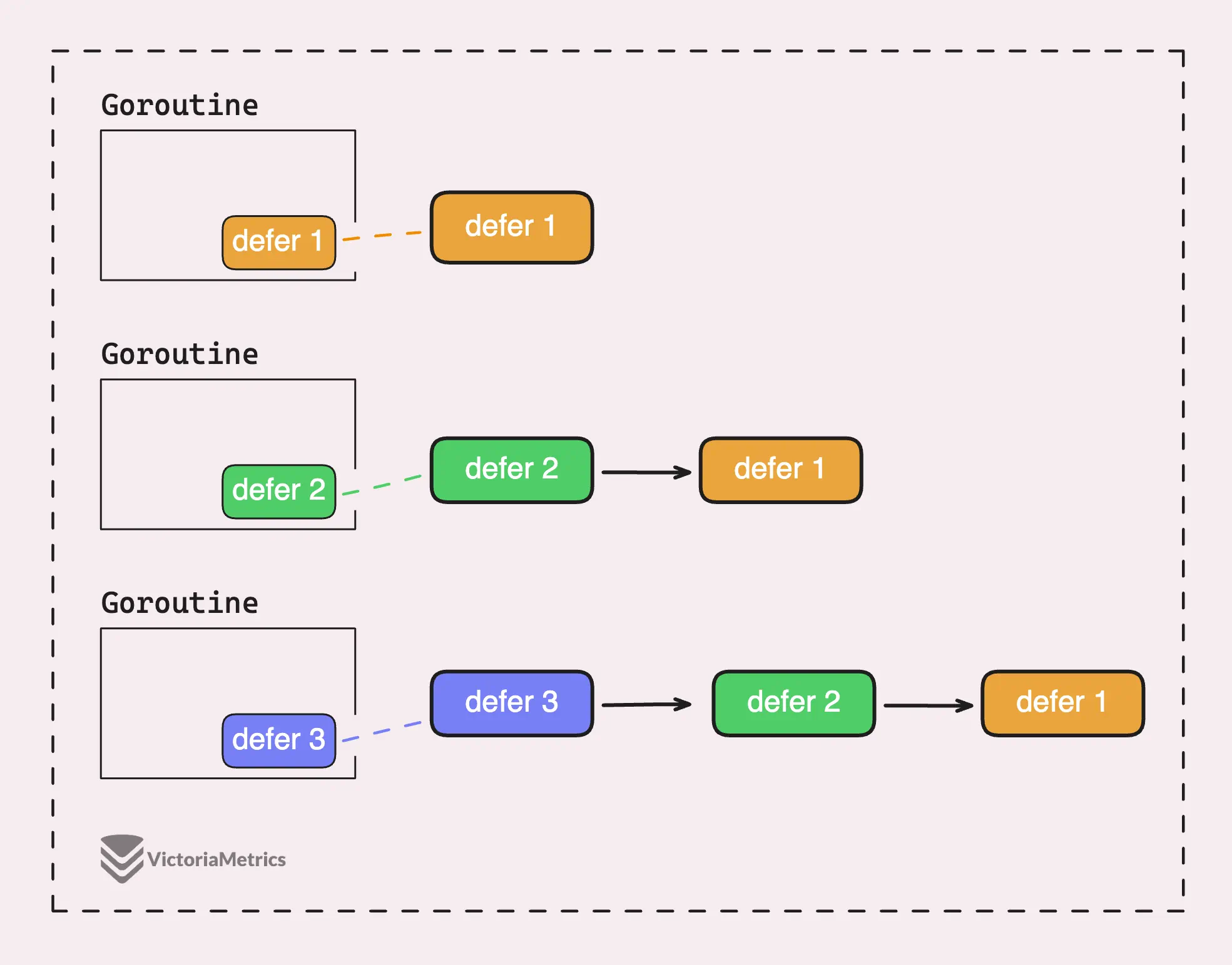

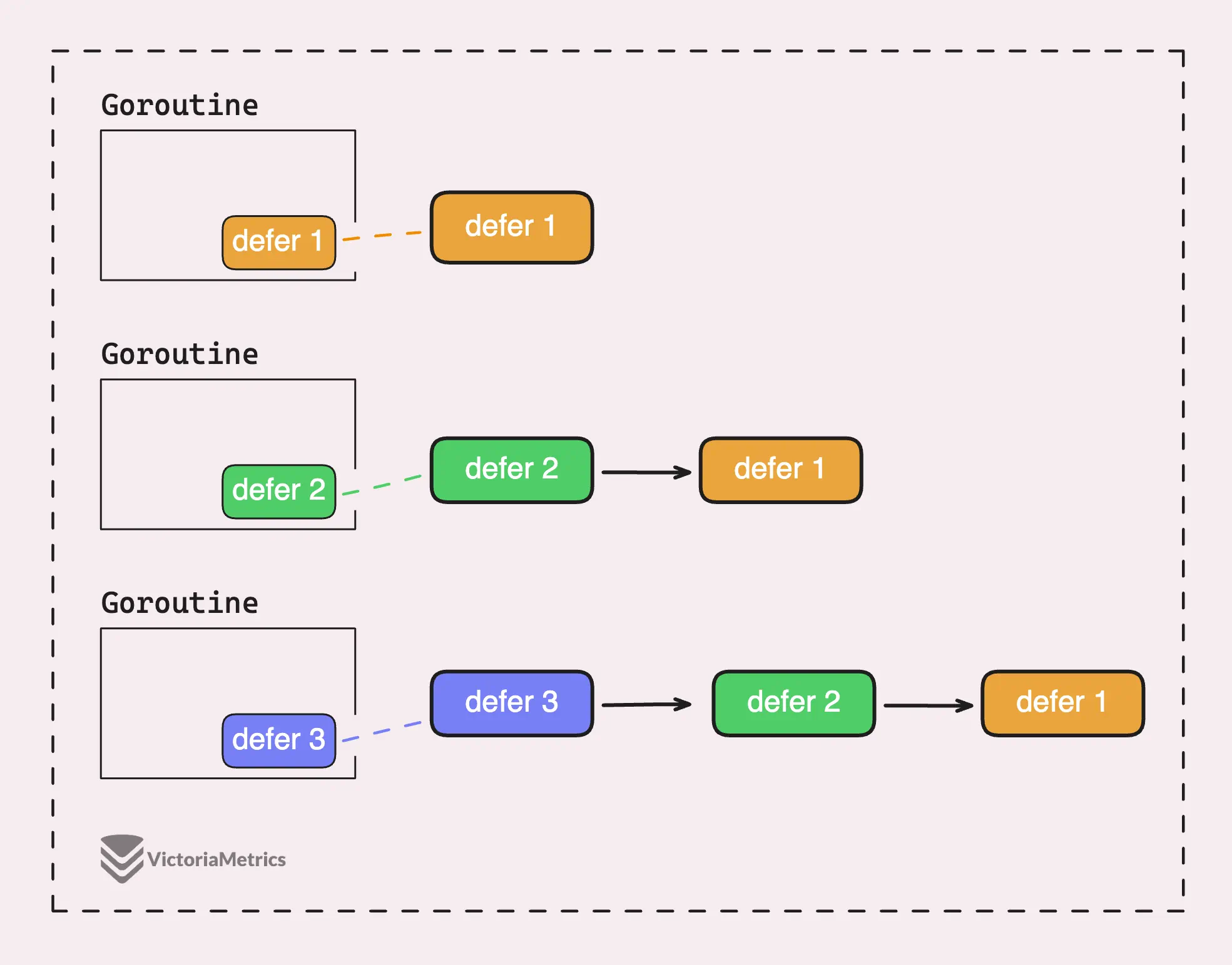

Every time you call a defer statement, you’re adding that function to the top of the current goroutine’s linked list, like this:

And when the function returns, it goes through the linked list and executes each one in the order shown in the image above.

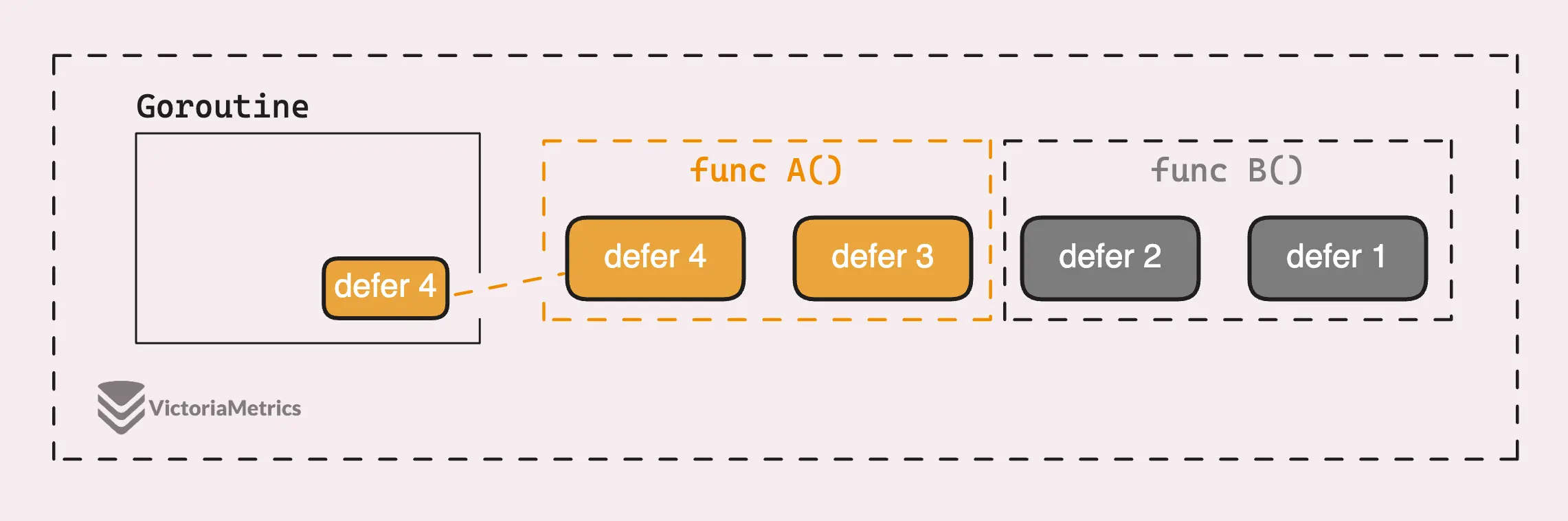

But remember, it does not execute all the defer in the linked list of goroutine, it’s only run the defer in the returned function, because our defer linked list could contain many defers from many different functions.

func B() {

defer fmt.Println(1)

defer fmt.Println(2)

A()

}

func A() {

defer fmt.Println(3)

defer fmt.Println(4)

}

So, only the deferred functions in the current function (or current stack frame) are executed.

But there’s one typical case where all the deferred functions in the current goroutine get traced and executed, and that’s when a panic happens.

Defer, Panic and Recover

#

Besides compile-time errors, we have a bunch of runtime errors: divide by zero (integer only), out of bounds, dereferencing a nil pointer, and so on. These errors cause the application to panic.

Panic is a way to stop the execution of the current goroutine, unwind the stack, and execute the deferred functions in the current goroutine, causing our application to crash.

To handle unexpected errors and prevent the application from crashing, you can use the recover function within a deferred function to regain control of a panicking goroutine.

func main() {

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

fmt.Println("Recovered:", r)

}

}()

panic("This is a panic")

}

// Output:

// Recovered: This is a panic

Usually, people put an error in the panic and catch that with recover(..), but it could be anything: a string, an int, etc.

In the example above, inside the deferred function is the only place you can use recover. Let me explain this a bit more.

There are a couple of mistakes we could list here. I’ve seen at least three snippets like this in real code.

The first one is, using recover directly as a deferred function:

func main() {

defer recover()

panic("This is a panic")

}

The code above still panics, and this is by design of the Go runtime.

The recover function is meant to catch a panic, but it has to be called within a deferred function to work properly.

Behind the scenes, our call to recover is actually the runtime.gorecover, and it checks that the recover call is happening in the right context, specifically from the correct deferred function that was active when the panic occurred.

“Does that mean we can’t use recover in a function inside a deferred function, like this?”

func myRecover() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

fmt.Println("Recovered:", r)

}

}

func main() {

defer func() {

myRecover()

// ...

}()

panic("This is a panic")

}

Exactly, the code above won’t work as you might expect. That’s because recover isn’t called directly from a deferred function but from a nested function.

Now, another mistake is trying to catch a panic from a different goroutine:

func main() {

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

fmt.Println("Recovered:", r)

}

}()

go panic("This is a panic")

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second) // Wait for the goroutine to finish

}

Makes sense, right? We already know that defer chains belong to a specific goroutine. It would be tough if one goroutine could intervene in another to handle the panic since each goroutine has its own stack.

Unfortunately, the only way out in this case is crashing the application if we don’t handle the panic in that goroutine.

Defer arguments, including receiver are immediately evaluated

#

I’ve run into this problem before, where old data got pushed to the analytics system, and it was tough to figure out why.

Here’s what I mean:

func pushAnalytic(a int) {

fmt.Println(a)

}

func main() {

a := 10

defer pushAnalytic(a)

a = 20

}

What do you think the output will be? It’s 10, not 20.

That’s because when you use the defer statement, it grabs the values right then. This is called “capture by value.” So, the value of a that gets sent to pushAnalytic is set to 10 when the defer is scheduled, even though a changes later.

There are two ways to fix this.

The first way is to use a closure. This means wrapping the deferred function call inside another function. That way, you capture the variable by reference, not by value like before.

func main() {

a := 10

defer func() {

pushAnalytic(a)

}()

a = 20

}

// Output:

// 20

The second way is to pass the memory address of the variable instead of its value.

func pushAnalytic(a *int) {

fmt.Println(*a)

}

func main() {

a := 10

defer pushAnalytic(&a)

a = 20

}

Both methods solve the issue, but using closures might be more idiomatic in Go, especially when dealing with simple variable captures.

“This is easy, I know it. You fell for this trap?”

Saying a language has a trap feels weird, right? But here’s the real trap I fell into:

type Data struct {

a int

}

func (d Data) pushAnalytic() {

fmt.Println(d.a)

}

func main() {

d := Data{a: 10}

defer d.pushAnalytic()

d.a = 20

}

// Output:

// 10

The output is actually 10, just like before.

This happens because the defer statement also evaluates its receiver immediately, capturing the value of d at that moment. Under the hood, the receiver is like an argument, so the defer statement works like this:

defer Data.pushAnalytic(d) // defer d.pushAnalytic()

So, the same rule applies: the arguments of the deferred function are evaluated right away.

Again, there are two ways to fix this, but they are a bit different from the previous examples with simple variables.

“We fix this by using a closure or pointer, right?”

Using a closure works, but just using a pointer isn’t enough. Even if we change Data{} to &Data{}, it won’t fix the problem because we’re still passing the dereferenced value to the deferred function:

d := &Data{}

defer Data.PushAnalytic(*d)

We need to change how we pass the receiver to the deferred function by switching from a value receiver to a pointer receiver.

func (d *Data) pushAnalytic() {

fmt.Println(d.a)

}

Good, now it works as expected.

To sum up, the deferred function’s arguments are evaluated when the defer statement is executed, or scheduled, not when the deferred function is called.

Defer with error handling

#

Now, back to the previous example where we open a file and close it. I said, ‘It is a good illustration point to show how defer works, but it’s also a bad example of how to use defer.’:

func doSomething() error {

f, err := os.Open("phuong-secrets.txt")

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer f.Close()

// ...

}

The problem is that if we use defer f.Close(), we miss the chance to handle the error gracefully because the Close method returns an error, but we miss it.

“Gracefully? You mean return the error to the caller?”

By “gracefully,” I mean we could just return the error to the caller or log the error for further investigation. We don’t want to lose the opportunity to understand our code better.

In our case, if the close method returns an error, it typically indicates that the file descriptor couldn’t be properly closed. This could be due to various reasons, like an interrupted system call or an underlying I/O error.

This is a big deal with software that needs high availability and reliability.

“But how do you return the error to the caller?”

To do that, we can’t just return error like usual, but by using defer and a named return value, we can achieve that.

func doSomething() (err error) {

f, err := os.Open("phuong-secrets.txt")

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer func() {

err = errors.Join(err, f.Close())

}()

// ...

}

So, even though we defer the Close method, we still effectively return any errors it produces by combining them with the original error using the named return value. Any nil will be discarded in errors.Join, so it’s safe to do in one line.

Note that, this example is showing you how defer could obscure the error, not focusing entirely on the opening & closing file problem.

Defer types: Heap-allocated, Stack-allocated and Open-coded defer

#

When we call defer, we’re creating a structure called a defer object _defer, which holds all the necessary information about the deferred call.

This object gets pushed into the goroutine’s defer chain, as we discussed earlier.

Every time the function exits, whether normally or due to an error, the compiler ensures a call to runtime.deferreturn. This function is responsible for unwinding the chain of deferred calls, retrieving the stored information from the defer objects, and then executing the deferred functions in the correct order.

The difference between heap-allocated and stack-allocated types is where the defer object is allocated. Below Go 1.13, we only had heap-allocated defer.

Currently, in Go 1.22, if you use defer in a loop, it will be heap-allocated.

func main() {

for i := 0; i < unpredictableNumber; i++ {

defer fmt.Println(i) // Heap-allocated defer

}

}

The heap allocation here is necessary because the number of defer objects can change at runtime. So, the heap ensures that the program can handle any number of defers, no matter how many or where they appear in the function, without bloating the stack.

Now, don’t panic, heap allocation is indeed considered bad for performance, but Go tries to optimize that by using a pool of defer objects.

We have two pools: a local cache pool of the logical processor P to avoid lock contention, and a global cache pool shared and taken by all the goroutines, which then put defer objects into processor P’s local pool.

“How about defer in the if statement in Go 1.22? It’s also unpredictable”

Good catch, putting defer in the if statement can be unpredictable.

Since Go 1.13, the defer can be stack-allocated and this means we craft the _defer object in the stack, then push it into the goroutine’s defer chain.

If the defer statement within the if block is invoked only once and not in a loop or another dynamic context, it benefits from the optimization introduced in Go 1.13, meaning the defer object will be stack-allocated.

func testDefer(a int) {

if a == unpredictableNumber {

defer println("Defer in if") // stack-allocated defer

}

if a == unpredictableNumber+1 {

defer println("Defer in if") // stack-allocated defer

}

for range a {

defer println("Defer in for") // heap-allocated defer

}

}

The above snippet holds true, even with Go 1.23.

With this optimization, according to the Open-coded defers proposal, in the cmd/go binary, this optimization applies to 363 out of 370 static defer sites. As a result, these sites see a 30% performance improvement compared to the previous approach where defer objects were heap-allocated.

If it’s that good, why do we need something called ‘open-coded defer’?

What if we just put the defer at the end of the function? The performance of a direct call is much better than the other two. As of Go 1.13, most defer operations take about 35ns (down from about 50ns in Go 1.12). In contrast, a direct call takes about 6ns.

You probably guessed it.

Go will inline our defer call directly at the end of the function and also before every return statement in the assembly code, but there are some restrictions for this type to be applied.

Remember the previous example above? Let me put it here again for easier discussion:

func testDefer(a int) {

if a == unpredictableNumber {

defer println("Defer in if") // stack-allocated defer

}

if a == unpredictableNumber+1 {

defer println("Defer in if") // stack-allocated defer

}

for range a {

defer println("Defer in for") // heap-allocated defer

}

}

If a function has at least one heap-allocated defer, any defer in the function will NOT be inlined or open-coded.

That means, to optimize the above function, we should remove or move the heap-allocated defer elsewhere.

func testDefer(a int) {

if a == unpredictableNumber {

defer println("Defer in if") // open-coded defer

}

if a == unpredictableNumber+1 {

defer println("Defer in if") // open-coded defer

}

}

Another thing to keep in mind is that the product of the number of defers in the function and the number of return statements needs to be 15 or less to fit into this category.

This is because we put the defer before every return statement, right? Our binary code will get pretty bloated if we have too many exit paths like that.

Also, after having a conversation, there are an interesting rules added by Cuong Le Manh - a well-known Golang contributor: “If the number of defer statements is more than 8, open-coded defer will not be applied.”

It turns out that, behind the scenes, open-coded defer is managed by a bitmask, which only has 8 bits. The purpose of open-coded defer is to optimize small functions, so it makes sense to have this restriction.

And that should be long enough for our today discussion.

Stay Connected

#

Hi, I’m Phuong Le, a software engineer at VictoriaMetrics. The writing style above focuses on clarity and simplicity, explaining concepts in a way that’s easy to understand, even if it’s not always perfectly aligned with academic precision.

If you spot anything that’s outdated or if you have questions, don’t hesitate to reach out. You can drop me a DM on X(@func25).

Related articles:

- Golang Series at VictoriaMetrics

- Go I/O Readers, Writers, and Data in Motion.

- Slices in Go: Grow Big or Go Home

- Go Sync Mutex: Normal and Starvation Mode

- Go Maps Explained: How Key-Value Pairs Are Actually Stored

- How Go Arrays Work and Get Tricky with For-Range

- Inside Go’s Unique Package: String Interning Simplified

- Vendoring, or go mod vendor: What Is It?

Who We Are

#

If you want to monitor your services, track metrics, and see how everything performs, you might want to check out VictoriaMetrics. It’s a fast, open-source, and cost-saving way to keep an eye on your infrastructure.

And we’re Gophers, enthusiasts who love researching, experimenting, and sharing knowledge about Go and its ecosystem.